The truly strong and sound mind is the mind that can embrace equally great things and small. I would have a man great in great things, and elegant in little things.

The Archetypal Super-Achiever

When you grow up you tend to get told the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much. Try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. Thats a very limited life.You can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use.

Steve Jobs

I m on my way to the factory. Meet me there. Click.

It was shortly after 8 a.m. on a Sunday in the fall of 1984. Steve Jobs was about to hop into his black Mercedes sedan to make the forty-minute trek from his home in Woodside to Fremont where Apple was churning out its latest productthe Macintosh computer.

On the receiving end of the phone line was Debi Coleman, the companys head of manufacturing, who had been sitting on her porch in Cupertino, buried in the Sunday paper. After two and a half years at Apple, she was accustomed to her bosss demanding and eccentric behaviorthe rage attacks, the intrusions during off-work hours, and the sudden disappearances for days at a time. I was less surprised by the timing of Steves call than by what I saw when I got there, recalled Coleman, now a partner at SmartForest, a Portland, Oregonbased venture capital firm.

Eager to build the perfect factory, Jobs had been badgering Coleman for months. After deciding in late 1983 that the initial siteDallas, Texaswould not do, Jobs became consumed with every detail. He wanted to bring to America the elegantly designed machines that he had seen in Germany such as Braun appliances and BMW cars. But his focus went way beyond acquiring state-of-the-art equipment. He insisted that the walls all be painted white. No white was too white for Steve, stated Coleman. Jobs would also don white gloves to do frequent dust checks. Whenever he spotted a few specks on either a machine or on the floor, which he was determined to keep clean enough to eat off, Coleman had to arrange for an instant scrubbing. Despite her frequent exasperation, Coleman did not think about quitting. I was mesmerized by his genius and charm. And like several other women in the company, I was a little bit in love with him, she added.

When Coleman arrived that Sunday, she noticed a side of Jobs that she had never seen before. He was particularly reserved and eager to please, Coleman noted. The reason? The normally high-octane entrepreneur, then still several months shy of his thirtieth birthday, had brought along a special guesthis adoptive father, Paul Jobs. From nine to eleven, Coleman escorted father and son around the nearly empty factory; in contrast to a weekday, when two shifts of workers would file in, only a few members of the security staff were present that morning. The facility was not yet completely finished, added Coleman, but Steve couldnt wait to show his father what he had created. A master craftsman himself, Paul Jobs, who had supported his family by working as a repo man, liked to build cabinets and fences. The elder Jobs also had a knack for fixing used cars. While his father was impressed by how everything worked, stated Coleman, he asked a lot of questions. He, too, paid attention to details.

While Steve Jobs did many great things at both Apple and Pixar, where he revolutionized the animation industry, he also never failed to keep track of the small things. And this intensity rattled many of his employees besides Coleman. Pamela Kerwin was the marketing director at Pixar when Jobs arrived in 1986, as his first stint at Apple was coming to an end. She was terrified whenever she printed anything for him to read, even memos. He was a control freak and perfectionist in all things, recalled Kerwin, now a principal at the Los Angeles tech firm Luminous Publishing. He would carefully go over every document a million times and would pick up on punctuation errors such as misplaced commas.

Commas. Cleanliness. Jobs could obsess and go ballistic about minutiae that would not even register on the radar screens of most CEOs. A tad mad, Jobs suffered from what psychiatrists call obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD). Though little studied, this condition affects as much as 8 percent of the U.S. population, according to a survey of more than forty thousand Americans published in 2012 in the Journal of Psychiatric Research. The current edition of psychiatrys bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, defines OCPD as a preoccupation with orderlinessand mental and interpersonal control and lists a total of eight common symptoms, four of which need to be present to reach the diagnosis. The key ones are:

- preoccupation with details, rules, order, lists, organization, or schedules

- perfectionism

- excess devotion to work

- inflexibility about matters of morality, ethics, or values

- reluctance to delegate tasks unless others submit to exactly his way of doing things

- rigidity and stubbornness

But for Jobs, these emotional difficulties didnt just impede his ability to get along with others; paradoxically, they also emerged as assetsthe very skill set that enabled him to create the behemoth that is now Apple. After all, in our fiercely competitive culture, being results oriented rather than relationship oriented has its advantages.

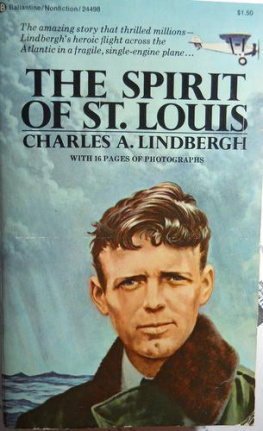

And Jobs is just one in a long ticker-tape parade of American iconsbeginning with Founding Fathers such as Thomas Jefferson and continuing through Pittsburgh entrepreneur Henry J. Heinz and Boston Red Sox star Ted Williamswhose obsessions and compulsions have fueled their stratospheric success. This list includes librarian Melvil Dewey, author of the pioneering search engine the Dewey Decimal Classification System, sexologist Alfred Kinsey, aviator Charles Lindbergh, and cosmetics tycoon Este Lauder, all of whom also led the way in their chosen fields. Like Jobs, the author of the Declaration of Independence kept sweating the small stuff. The man who gave us the pennyhis 1784 paper Notes on the Establishment of a Money Unit, and of a Coinage for the United States organized our national currencycouldnt help but keep track in his copious account books of every cent that he ever spent. And Jeffersons attention to detail was also responsible for the better-known chunks of his legacyhis brilliant writing, his pioneering architecture, and the University of Virginia, the exemplary public institution of higher learning that he founded. Like Jefferson, Heinz, who turned ketchup into our national sauce at the dawn of the twentieth century, had an obsession with counting, which he used to create one of the most successful slogans in advertising history, 57 Varieties. Slavishly devoted to his craft, Ted Williams was also an order and cleanliness nut. When visiting the Red Sox spring training facility in the late 1970s, the retired Hall of Famer would pester the clubhouse attendant about why he used Tide on the teams laundry. This ballplayer didnt hit to live, he lived to hit; and until the day he died, he loved nothing more than talking about the perfect swing.

To describe this exclusive group of archetypal super-achievers, of whom Jobs is the most prominent recent example, I prefer to use a term of my own coinage: obsessive innovator. Current nomenclature can be misleading because we tend to associate obsessives solely with careful, plodding performance. While the consultant Jim Collins, author of the megaselling Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leapand Others Dont (2001), puts obsessives at the top of his leadership pyramid, he contends that these Level 5 Leaders are mild-mannered, self-effacing types and not creative trailblazers. Making the same assumption about those suffering from OCPD, authors who have recently explored the link between madness and greatness assign other psychiatric maladies to our biggest movers and shakers. For example, in