Playing in Time

Essays, Profiles, and Other True Stories

CARLO ROTELLA

The University of Chicago Press * Chicago and London

CARLO ROTELLA is the author of Good with Their Hands: Boxers, Bluesmen, and Other Characters from the Rust Belt; October Cities: The Redevelopment of Urban Literature; and Cut Time: An Education at the Fights, the last also published by the University of Chicago Press. He writes regularly for the New York Times Magazine, Washington Post Magazine, and Boston Globe, and he is a commentator for WGBH FM in Boston.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2012 by Carlo Rotella

All rights reserved. Published 2012.

Printed in the United States of America

| 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 | 12345 |

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-72909-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-72911-4 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-226-72909-5 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-72911-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rotella, Carlo, 1964

Playing in time : essays, profiles, and other true stories / Carlo Rotella.

pages ; cm

Miscellaneous essays.

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-72909-1 (cloth : alkaline paper)

ISBN-10: 0-226-72909-5 (cloth : alkaline paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-72911-4 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-226-72911-7 (e-book)

I. Title.

AC8.R644 2012

814.6dc23

2011050360

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

Contents

FOR MY BROTHERS, Sebastian and Sal

Introduction: The Lefty Dizz Version

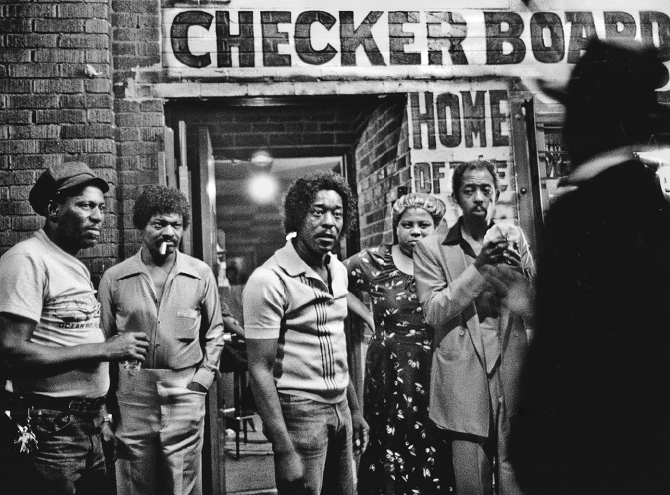

ON THE WALL BY my desk I have mounted a photograph of a confrontation on the sidewalk outside the Checkerboard Lounge, at 43rd and Vincennes on the South Side of Chicago, in 1982. In the picture, the great bluesman Buddy Guy, who owned the Checkerboard back then, faces off against a young man in a hat who has his back to the camera. The young man, ejected from the club after some kind of beef, had stormed off to his car and returned wearing a jacket, with one hand jammed menacingly into one of its pockets. Guy and a crew of his supporters are lined up shoulder to shoulder to bar the way to the door, each privately calculating the odds that the young man really has a gun and would use it. Backing up the boss, from left to right, are Anthony, Guys aide-de-camp and security man; L. C. Thurman, who managed the club; and Aretta, who tended bar and waited tables. Standing with them, although he seems more observer or bystander than participant, is Lefty Dizz, a bluesman from Osceola, Arkansas, who hung out at the Checkerboard and hosted its Blue Monday jam for years.

Unlike the others, who strike appropriately forbidding posesAnthony with drink in hand, Thurman with cigarette balefully pasted in mug, Aretta with hands on hips in iconic disapproval, Guy front and center with his whole being concentrated in the hands-down, shoulder-forward, head-cocked ready position that indicates a willingness to go all the wayDizz seems bemused, even distracted. Hes the only one not fixing the troublemaker with a grim stare, and hes holding something soft and bulky in front of him with both hands, probably a balled-up towel, presenting it with palms inward, like an offering or talisman. The others body English says, Mess with me and youll regret it. Dizzs says, Life is complex and filled with contingency; this would be a good time to step within for a taste of Old Grand-Dad.

I like to look at this picture, to which attaches a fugitive whiff of the South Side tavern bouquet of my youth: menthol cigarettes, Old Style beer, and hair treatments made by the Johnson Products Company. And theres the pleasure of seeing familiar faces, people with whom I exchanged friendly words on big nights out in my teens, which means its going on 30 years since I used to see them all a couple of times a week. But I also keep the picture around as a reminder to take second and third looks, to revisit scenes and characters and stories that I thought I knew well.

Marc PoKempner, a longtime photographer of the Chicago blues scene, happened to pull up at the curb outside the Checkerboard on his motorcycle on that summer night in 1982 just in time to shoot a sequence of pictures of the confrontation. I used a different shot from his sequence in a book called Good with Their Hands, published a decade ago. That one was taken from an angle farther around behind the young troublemaker, so that he almost entirely obscures Dizz. Guy has stepped more prominently forward in that one, Arettas not in it, and Thurman (who later wrested control of the Checkerboard from Guy) looks off to the side, all of which has the effect of making Guy seem isolated as he attends to yet another problem that an egregio virtuoso should be able to leave to his underlings. I put it in the book to evocatively illustrate Guys account of how difficult it was to run a club on the South Side in the 1970s and 1980s.

The Lefty Dizz version may not be a better picture in the conventional senseyes, the poses are more dramatic, but the troublemakers free hand is blurred, and Dizz, too, is not quite perfectly in focusbut it has an added valence that matters. Guy was the marquee name, the guitar hero whose ownership of the Checkerboard gave it a reputation as the capital of Chicago blues and attracted fellow greats like Muddy Waters and Otis Rush, insiders favorites like Fenton Robinson and Magic Slim, and rock stars like the Rolling Stones and Stevie Ray Vaughan, who dropped by the Checkerboard after playing sold-out arena gigs. Dizz, the only person Ive ever known who bore a close resemblance to the Cat in the Hat, was by comparison a minor figure, a local character known for a couple of novelty songsIm sitting here drinking my eggnog, but theres nobody to drink with me / Its the 25th of December, and Im sad as a man can beand for his gift for orchestrating a good time. He had a serviceable voice and a droll showbiz manner, and he was a distinctive, if limited, guitar player. He did a great deal of one-handed playing, part of a large repertoire of onstage gimmickry, but he wasnt all tricks; he had learned a thing or two about propulsive grooves from the blues-party juggernaut Hound Dog Taylor. Thanks to the quality of local talent and in great part to Dizz, an ideal emcee, the Checkerboards Monday night blues jam was a cut above all others. It usually started out in desultory fashion but built in intensity as musicians, patrons, smoke, inebriation, and sound accrued in the narrow, low-ceilinged room until some magical fission point was attained. On Tuesdays, still lost in the previous nights music, Id go around in a daze at schoolmore of a daze than usual, that is.

Dizz, whose given name was Walter Williams, was the most approachable of the Checkerboards notables. A generous fellow and a natural-born enthusiast, he showed a particular affection for the kids from my high school who hung out there. Dizz, who had studied economics at Southern Illinois University, enjoyed playing the down-home blues sage as much as we enjoyed playing at being barflies and connoisseurs. Each indulged the other. I liked to ask technical questions: How do you make a song yours when other players already made it famous? He liked to drop aphoristic advice on whippersnappers: Take your time and listen. Dont be all in a rush to play fast and blow everybody away. Take your time, and youll hear that note in that song that nobody else has heard. He played an annual gig at my school, staying up all night with his band, the Shock Treatment, to make the early-morning assembly in the gym, where, bleary-eyed in his third-best suit, he played a short set of his old reliables: Baby, Please Dont Go, The Things I Used to Do, Never Make My Move Too Soon, Bad Avenue, Somebody Stole My Christmas.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992