Chapter 1. A Problem

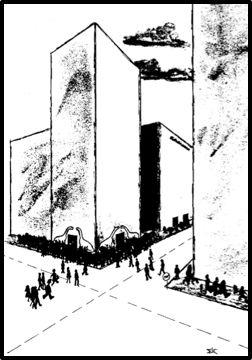

In the heart of Gotham City's financial district stands the glistening new 73-story Brontosaurus Tower. Even though this architectural masterpiece is not yet fully occupied, the elevator service has been found woefully inadequate by the tenants. Some tenants have actually threatened to leave if the service isn't improved, and quickly.

Figure 1. Brontosaurus Tower

A few facts of the case are as follows:

(1) The building primarily houses offices doing business during the weekday hours of 9am to 5pm.

(2) Nearly everyone using the building is associated in some way with the financial world.

(3) The occupants are fairly uniformly distributed over the 73 floors, and so is the elevator traffic.

(4) The owner has invested heavily in advertising in an attempt to rent the remaining office space.

(5) Discouraging words spread like lightning in the tight little world of the financial district.

WHAT IS TO BE DONE ABOUT THIS SITUATION?

A number of ideas spring immediately to mind, such as:

(1) Speed up the elevators.

(2) Add elevators by cutting new shafts through the building.

(3) Add elevators by constructing outside shafts.

(4) Stagger working hours to spread the rush hour load over a longer period.

(5) Move occupants to different floors to reduce total passenger traffic within the building.

(6) Restrict the number of people entering the building.

(7) Replace existing elevators with bigger cars stretching two or three stories.

(8) Provide more services locally on each floor to reduce floor-to-floor traffic.

(9) Reschedule the elevators with special local and express arrangements, as needed.

Having followed our natural problem-solving tendencies, we have rushed right into solutions. Perhaps it would be wiser to ask a few questions before stating answers.

What sorts of questions? Who has the problem? What is the problem? Or, at this juncture, just what is a problem ?

Consider the question, "Whose problem is it?" This question attempts to

(1) determine who is the clientthat is, who must be made happy

(2) establish some clues that may lead to appropriate solutions.

Our first list of solutions, diverse as they were, all shared a single point of viewthat the elevator users were the people with the problem.

Suppose we try taking the point of view of Mr. Diogenes Diplodocus, the landlord. With him as our client, we might develop a rather different list, such as:

(1) Increase the rents, so fewer occupants will be needed to pay off the mortgage.

(2) Convince the occupants that Brontosaurus Tower is a terrific leisurely place to work because of the elevator situation.

(3) Convince the occupants that they need more exercisewhich they could get by walking the stairs rather than riding the elevatorsby posting walking times and calorie consumption estimates over well- traveled routes.

(4) Burn down the building and collect the fire insurance.

(5) Sue the builder.

(6) Steal elevator time from the next-door neighbor.

These two lists, though not necessarily mutually exclusive, do show somewhat different orientations. This difference should arrest our natural tendency to produce hasty solutions before asking

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

The fledgling problem solver invariably rushes in with solutions before taking time to define the problem being solved. Even experienced solvers, when subjected to social pressure, yield to this demand for haste. When they do, many solutions are found, but not necessarily to the problem at hand. As each person competes for acceptance of a favored solution, each one accuses the other of stubbornness, not of having an alternative point of view.

Not every problem-solving group founders on lack of attention to definition. Some come to grief by endlessly circling around attempted definitions, never amassing the courage to get on with the solution in spite of definitional dangers.

As a practical matter, it is impossible to define natural, day-to-day problems in a single, unique, totally unambiguous fashion. On the other hand, without some common understanding of the problem, a solution will almost invariably be to the wrong problem. Usually, it will be the problem of the person who talks loudest, or most effectively. Or who has the biggest bank account.

For the would-be problem solver, whose problem is to solve the problems of others, the best way to begin is mentally to shift gears from singular to plural from Problem Solver to Problems Solver, or, if you find that hard to pronounce, to Solver of Problems.

To practice this mental shift, the Solver should, early in the game, try to answer the question;

WHO HAS A PROBLEM?

and then, for each unique answering party, to ask

WHAT IS THE ESSENCE OF YOUR PROBLEM?

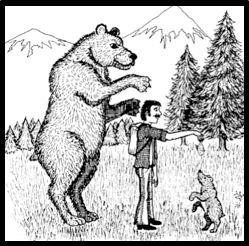

Figure 1.2. What is the essence of your problem?

Chapter 2. Peter Pigeonhole Prepares a Petition

From the perspective of the office workers, the Brontosaurus problem might be stated as

HOW CAN I COVER MY APPOINTED ROUNDS WITH MINIMUM TIME, EFFORT, AND/OR AGGRAVATION?

For Mr. Diplodocus, the problem may be abstracted to

HOW CAN I DISPOSE OF ALL THESE BLANKETY-BLANK COMPLAINTS?

If these two parties (are there others?) cannot get together, a mutually satisfactory solution seems improbable. Unpleasant as the prospect may be, an effective problems solver must work towards achieving a meetingif not of minds, then of bodies.

In order to call the landlord's attention to "the problem," a mailboy at Finicky Financial Fiduciary, Peter Pigeonhole, prepares a petition. Using his role as mailboy, he is able to obtain an impressive list of signatures at 3F. Using his class connections with other firms' mailboys, he expands the list.