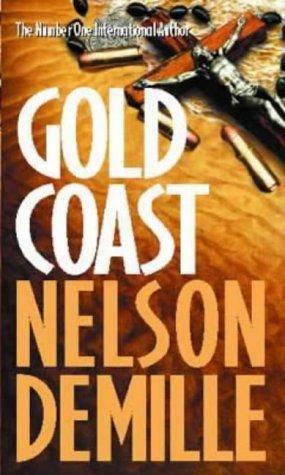

The first book in the John Sutter series

To my three budding authors: Ryan, Lauren, and Alex.

I wish to thank Daniel and Ellen Barbiero for sharing with me their invaluable insights into Gold Coast life, and also Audrey Randall Whiting for sharing with me her knowledge of Gold Coast history.

I would also like to acknowledge my gratitude to John Mariani and Harry Mariani for their generous hospitality and support.

I also want to thank Pam Carletta for her tireless and professional work on the manuscript of this book.

And once again, my deepest gratitude to Ginny De Mille, editor, publicist, and good friend.

A man lives not only his personal life as an individual, but also, consciously or unconsciously, the life of his epoch and his contemporaries.

Thomas Mann

The Magic Mountain

The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.

Walt Whitman

Preface to Leaves of Grass

I first met Frank Bellarosa on a sunny Saturday in April at Hicks' Nursery, an establishment that has catered to the local gentry for over a hundred years. We were both wheeling red wagons filled with plants, fertilizers, and such toward our cars across the gravel parking field. He called out to me, "Mr Sutter? John Sutter, right?"

I regarded the man approaching, dressed in baggy work pants and a blue sweatshirt. At first, I thought it was a nurseryman, but then as he drew closer, I recognized his face from newspapers and television. Frank Bellarosa is not the sort of celebrity you would like to meet by chance, or in any other way, for that matter. He is a uniquely American celebrity, a gangster actually. A man like Bellarosa would be on the run in some parts of the world, and in the presidential palace in others, but here in America he exists in that place that is aptly called the underworld. He is an unindicted and unconvicted felon as well as a citizen and a taxpayer. He is what federal prosecutors mean when they tell parolees not to 'consort with known criminals'. So, as this notorious underworld character approached, I could not for the life of me guess how he knew me or what he wanted or why he was extending his hand toward me. Nevertheless, I did take his hand and said, "Yes, I'm John Sutter." "My name's Frank Bellarosa. I'm your new neighbour." What? I think my face remained impassive, but I may have twitched. "Oh," I said, "that's" Pretty awful.

"Yeah. Good to meet you."

So my new neighbour and I chatted a minute or two and noted each other's purchases. He had tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, and basil. I had impatiens and marigolds. Mr Bellarosa suggested that I should plant something I could eat. I told him I ate marigolds and my wife ate impatiens. He found that funny. In parting, we shook hands without any definite plans to see each other again, and I got into my Ford Bronco.

It was the most mundane of circumstances, but as I started my engine, I experienced an uncustomary flash into the future, and I did not like what I saw.

I left the nursery and headed home.

Perhaps it would be instructive to understand the neighbourhood into which Mr Frank Bellarosa had chosen to move himself and his family. It is quite simply the best neighbourhood in America, making Beverly Hills or Shaker Heights, for instance, seem like tract housing.

It is not a neighbourhood in the urban or suburban sense, but a collection of colonial-era villages and grand estates on New York 's Long Island. The area is locally known as the North Shore and known nationally and internationally as the Gold Coast, though even realtors would not say that aloud. It is an area of old money, old families, old social graces, and old ideas about who should be allowed to vote, not to mention who should be allowed to own land. The Gold Coast is not a pastoral Jeffersonian democracy. The nouveau riches, who need new housing and who comprehend what this place is all about, are understandably cowed when in the presence of a great mansion that has come on the market as a result of unfortunate financial difficulties. They may back off and buy something on the South Shore where they can feel better about themselves, or if they decide to buy a piece of the Gold Coast, they do so with great trepidation, knowing they are going to be miserable and that they had better not try to borrow a cup of Johnnie Walker Black from the people in the next mansion.

But a man like Frank Bellarosa, I thought, would be ignorant of the celestial beings and great social icebergs who would surround him, completely unknowing of the hallowed ground on which he was treading.

Or, if Frank Bellarosa was aware, perhaps he didn't care, which was far more interesting. He struck me, in the few minutes we spoke, as a man with a primitive sort of elan, somewhat like a conquering soldier from an inferior civilization who has quartered himself in the great villa of a vanquished nobleman.

Bellarosa had, as he indicated, purchased the estate next to mine. My place is called Stanhope Hall; his place is called Alhambra. The big houses around here have names, not numbers, but in a spirit of cooperation with the United States Post Office, my full address does include a street, Grace Lane, and an incorporated village, Lattingtown. I have a zip code that I, like many of my neighbours, rarely use, employing instead the old designation of Long Island, so my address goes like this: Stanhope Hall, Grace Lane, Lattingtown, Long Island, New York. I get my mail.

My wife, Susan, and I don't actually live in Stanhope Hall, which is a massive fifty-room beaux-arts heap of Vermont granite, for which the heating bills alone would wipe me out by February. We live in the guesthouse, a more modest fifteen-room structure built at the turn of the century in the style of an English manor house. This guesthouse along with ten acres of Stanhope's total two hundred acres were deeded to my wife as a wedding present from her parents. However, our mail actually goes to the gatehouse, a more modest six-room affair of stone, occupied by George and Ethel Allard.

The Allards are what are called family retainers, which means they used to work, but don't do much anymore. George was the former estate manager here, employed by my wife's father, William, and her grandfather, Augustus. My wife is a Stanhope. The great fifty-room hall is abandoned now, and George is sort of caretaker for the whole two-hundred-acre estate. He and Ethel live in the gatehouse for free, having displaced the gatekeeper and his wife, who were let go back in the fifties. George does what he can with limited family funds. His work ethic remains strong, though his old body does not. Susan and I find we are helping the Allards more than they help us, a situation that is not uncommon around here. George and Ethel concentrate mostly on the gate area, keeping the hedges trimmed, the wrought-iron gate painted, clipping the ivy on the estate walls and the gatehouse, and replanting the flower beds in the spring. The rest of the estate is in God's hands until further notice.

I turned off Grace Lane and pulled up the gravel drive to the gates, which are usually left open for our convenience, as this is our only access to Grace Lane and the wide world around us.

George ambled over, wiping his hands on his green work pants. He opened my door before I could and said, "Good morning, sir."

George is from the old school, a remnant of that small class of professional servants that flourished so briefly in our great democracy. I can be a snob on occasion, but George's obsequiousness sometimes makes me uneasy. My wife, who really was to the manner born, thinks nothing of it and makes nothing of it. I opened the back of the Bronco and said, "Give me a hand?" "Certainly, sir, certainly. Here, you let me do that." He took the flats of marigolds and impatiens and laid them on the grass beside the gravel drive. He said, They look real good this year, Mr Sutter. You got some nice stuff. I'll get these planted 'round the gate pillars there, then I'll help you with your place."

Next page