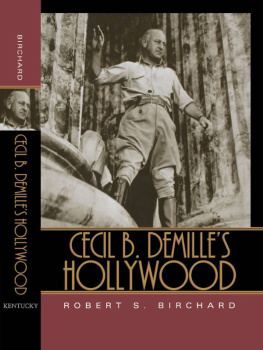

Cecil B. DeMilles

Hollywood

Cecil B. DeMilles

Hollywood

R OBERT S. B IRCHARD

With a foreword

by KevinThomas

T HE U NIVERSITY P RESS OF K ENTUCKY

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2004 by Robert S. Birchard

The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

10 09 08 07 06 6 5 4 3 2

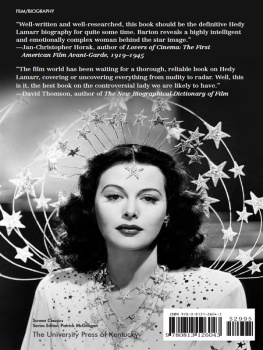

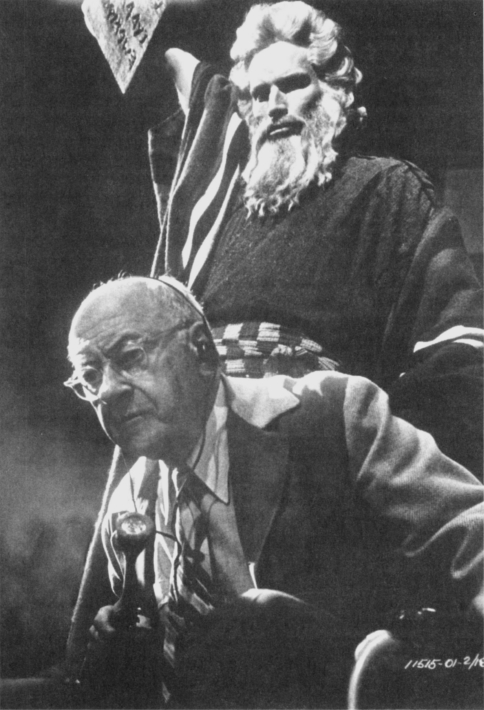

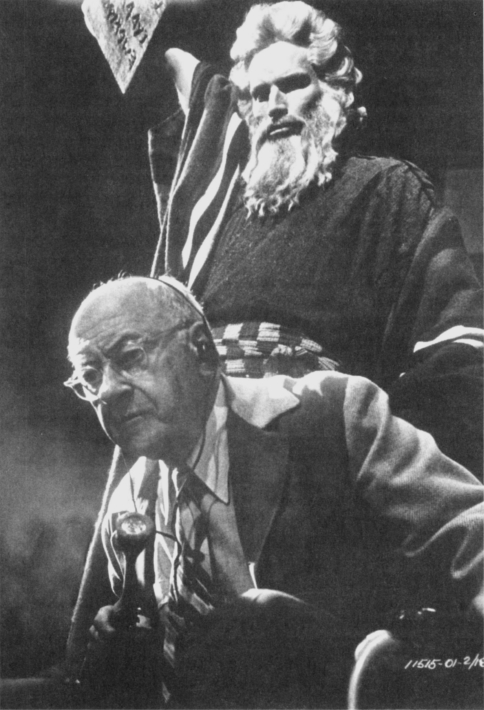

Frontispiece: Handing down the Law. Cecil B. DeMille and Charlton Heston during production of The Ten Commandments (Paramount, 1956). (Authors collection)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Birchard, Robert S.

Cecil B. DeMilles Hollywood / Robert S. Birchard.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-2324-0 (alk. paper)

1. DeMille, Cecil B. (Cecil Blount), 1881-1959.2. Motion picturesUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

PN1998.3.D39B57 2004

791.430233092dc22

2003024585

ISBN: 978-0-8131-2324-0

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

For Grace Houghton

who kept the faith

Foreword

I n 19891 had the honor of introducing the Silent Societys seventy-fifth anniversary screening of Cecil B. DeMilles The Squaw Man in the Lasky-DeMille Barn, home of the Hollywood Heritage Museum today and the very building from which DeMilles first film was produced. It was a special thrill for me because my relatives citrus orchards once began across the street from the Barns original location at Vine Street and Selma Avenue, extending many blocks to where the Egyptian Theater stands today. But I quickly brought Robert Birchard to the stage, knowing of his passion and knowledge of DeMille. His remarks then and there made it clear that he was the man to write this definitive survey of the films and career of Cecil B. DeMille.

As a veteran film editor and an experienced film historian, Birchard is uniquely qualified to judge DeMille and his accomplishmentsartistically, technically, and historically. We learn how much DeMilles movies cost, how much they made (or on occasion, lost), and how long they took to make, where they were made, and under what conditions. Cecil B. DeMilles Hollywood is a detailed study of DeMilles films and their impact, not a biography of the director. Yet Birchard illuminates the directors relations with his colleagues so thoroughly that we get an idea of what DeMille was like through this documented history perhaps more strongly than we would through the inherently conjectural nature of conventional biography. DeMille emerges as a man of tremendous drive and dedication, concerned with making a contribution through his work, and on the whole much more likable than one would have imagined.

Today DeMille is best remembered for his colossal 1956 remake of his 1923 silent The Ten Commandments, for which Charlton Heston has good-naturedly endured a zillion Parting-of-the-Red-Sea jokes. It is the epitome of the biblical spectacles for which DeMille was so famous, those with a seeming cast of thousands and filled with pagan revels featuring scantily clad beauties, as the director was a firm believer in showing sin in action in order to effectively condemn it. DeMille is also remembered for his 1952 circus extravaganza, The Greatest Show on Earth, which won the Oscar for Best Picture, and for his 1927 silent story of Jesus, The King of Kings, which has a simple beauty and deep spirituality that surprise many who only think of DeMille as the most unabashed of showmen.

That DeMille showed an instinct for the cinema and its endless possibilities is startlingly evident right from the beginning with The Squaw Man, which may be an adaptation of a play, but in its unfolding makes excellent use of its expansive natural locales. Also from the start, DeMille loved to mix highly theatrical hokum with often pious sentiments and technical finesse, which made him more cherished by audiences than critics. Yet it was his natural flair for screen storytelling and his patent sincerity that make his films so enduringly entertaining and their messages, in some instances, valid even still. It is important to see his work and those of his contemporaries, most notably D.W. Griffith, as expressions of a Victorian sensibility committed to uplift as much as entertainment.

Nobody would ever place DeMille on the same level of artistic genius as Griffith, but time and again Birchard shows how far more complex and wide-ranging a filmmaker DeMille really was, capable of sympathies and concerns for the individual and for society that are at odds with his conservative political image. What is also surprising to learn is that Paramount head Adolph Zukor kept as tight a rein as possible on his star director and especially resented maintaining a separate production unit for him. Long simmering tension between the two men would finally erupt in the wake of cost overruns on the original Ten Commandments, leading DeMille to be forced out of Paramount for a difficult seven-year period, during which he nevertheless showed just as strong a flair for talkies as he had for silents. DeMille returned to Paramount in the depths of the Great Depression and soon hit the long successful stride that would sustain his career until the end of his life in 1959.

DeMille had a reputation for being the most imperial of directors on the set, but Birchard argues effectively that this was his way of keeping outsized egos on either side of the camera in line, and that DeMille was remarkably loyal, going to great lengths to ensure work for veteran players whose moment of fame and fortune had long since passed. Cecil B. DeMilles Hollywood is a major achievement, a model of clarity, judgment, and informative and revealing detail, and constitutes a long-overdue comprehensive and serious evaluation of the wide-ranging accomplishments and contributions of a legendary, enduringly successful Hollywood pioneer.

Kevin Thomas

Los Angeles Times film critic

Preface

I n those days there were three great directors D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, and Max von Mayerling. Erich von Stroheim speaks this line in Billy Wilders film a clef, Sunset Boulevard(Paramount,1950). In the film Stroheim portrays the fictional von Mayerling, a once-famous film maker reduced to serving as butler to one of his former stars. The dialogue is poignant because in some sense Stroheim the actor is speaking of himself and his own vanished career as a director. Similarly, D.W. Griffith was ultimately unable to find work in the industry he helped create. But what of Cecil B. DeMille? In

Next page