Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

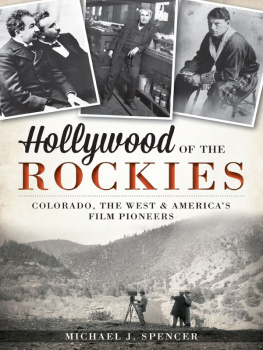

Copyright 2013 by Michael J. Spencer

All rights reserved

Front cover, clockwise from left: Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Museum of the City of New York / Art Resource, New York; Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; History Colorado.

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.652.5

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.60949.743.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Acknowledgements

They say that film is a collaborative art. In many ways, its the same with a book: the author gets a lot of help from a lot of sources. So, Id like to take the time here to give a big thanks to the people and the institutions that helped me put this book together and made their resources available to me.

First, of course, is Rocky Mountain PBS, where my original television documentary began. And for particular help in reassembling some of my notes from that time, Id like to acknowledge Donna Sanford and Diane Ceraficci. The program was originally a part of the Rocky Mountain Legacy series, executive produced by Sherry Niermann.

Im truly indebted to Janet Lorenz of the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Starting from years ago with the documentary, she has been able to track down both obscure and not-so-obscure images and information with equal ease.

Coi Drummond-Gehrig and Bruce Hanson with the Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, helped to corral the items in their vast and wonderful collection, which is superbly managed by Jim Kroll.

I received tireless assistance from Sarah Gilmor at History Colorado, especially in helping to track down images and information that I, at first, thought might be impossible to find.

David Emrich is the dean of Colorado film history. Hes researched the topic for years, and his own private collection is extensive. He acted as consultant for the television documentary.

David Kiehns knowledge and research is unfathomable. Hes also the historian of the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum in Niles, California, devoted to silent film in general and Essanay films in particular. Hes the go-to source for all things Gilbert Anderson.

Thanks to the Columbia University Center for Oral History for supplying the transcript of conversations held with Gilbert Anderson in 1958.

And finally, where would I be without Steve Hansen? Im indebted to you, not just as a researcher but also as a friend for life.

A Note on the Books Organization

The book is divided into three parts, and each has a separate story. I tell you this so you wont get lost and wander around the pages, unsure where youre going.

gives a few hints on where to view some of these movies today.

PART I

EXPLORERS OF THE FILM FRONTIER

This is a book about an age of filmmaking that most people dont even know existed. Its a book about a group of people that, almost by accident, pulled movies out of the realm of novelty and into the realm of businessand ultimately into the realm of art.

These days, people think of early cinemaif they think of it at allas the luminous outpouring of Hollywoods Golden Age of the 1930s or 40s. A few hardy fans of silent film will reminisce about the soundless glories of the 1920s. The more daring will extend their applause back into the 1910s. So it might come as a surprise to find that there was a fierce industry flourishing long before all of that. The movie business was already thriving before Charlie Chaplin first shambled in front of a camera or Douglas Fairbanks leaped onto the screen or Mary Pickford sighed demurely on film.

This is the story of those early daysmore particularly, a specific part of those days: a part lying west of New York but east of California, in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. Its a tale of the role that the West played in shaping the American film industry. Of course, there were many early film pioneers who didnt film in the West, but there were many who did. And this is their story.

All things seem to change a little when they pass through Colorado. Its a crossroads of sorts, where people and ideas come together, collide, merge, become inspired, create some new spark and pop out the other end completely changed animals. Even the weather becomes more than the weather; this is where the winds and breezes moving across the country hit the mountains and transform themselves into giant storms and towering thunderheads or dissipate into gentle zephyrs. Either way, theyve been changed.

And so it was that in the early twentieth century, the area served as a sort of incubator for ideas that were traveling through the country and would eventually move on and reach their zenith in what would become the film capital known as Hollywood. Ultimately, it was more than the scenery that affected the filmmakers, these newcomers to the Front Range of the Colorado Rockiesit was an indefinable something in the very air.

It was, however, the landscape that brought them there in the first place. Colorado rather lucked out with its gorgeous, natural scenery, perfect for the countrys (and the worlds) growing infatuation with the West. The most important star of these films wasnt in the cast; rather, it was the Colorado West itself. It helped create the western, a genre that remained a staple of American films for decades. And though the western film is certainly not the box office draw it once was, its spirit still inhabits the soul not only of American films but international films as well.

More importantly, it led moving pictures to realize what they really are by revealing their quality of locationnessthe authenticity of place that lifts films from the burden of merely documenting staged performances. Landscape and setting became just as significant as character and plot (and, importantly to the early film entrepreneurs, made for significant box office profits as well). It began when movies discovered the vast expanse of open space and embraced the mythos of the West.

To be sure, Colorado wasnt the only western state to play host to the pioneering filmmakers. Wyoming, Montana, Oklahoma, Arizona and New Mexico are just a few of the other states that lent their scenery to the growing film industry. But Colorado had just about the best back lot imaginable, and those early filmmakers used it to its best advantage.

Watching these old films today, frankly, they look pretty beat up. A lot of this, of course, is simply the result of agethe scratchy, bouncing images rendered unsteady because of overrunning through a projector. But even looking beyond that, theres definitely a certain primitivism to these films. The action is conspicuously staged, and the characters are awkwardly posed for benefit of the completely static camera position: a close approximation of the best seat in a live theaterfront row, center. But if you look at these films through different, un-modern eyes, you see that they captured a raw naturalism, a genuineness of human interaction that is often lacking in present-day films. Perhaps weve all become too enamored of todays sophisticated production values.

Next page