IMAGES

of America

EARLY POVERTY

ROW STUDIOS

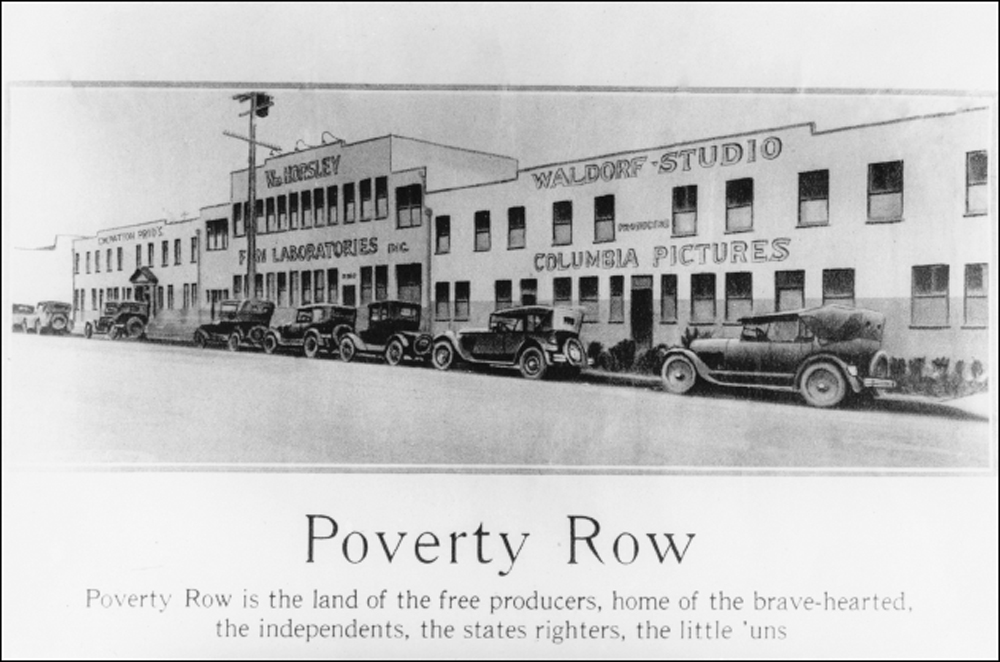

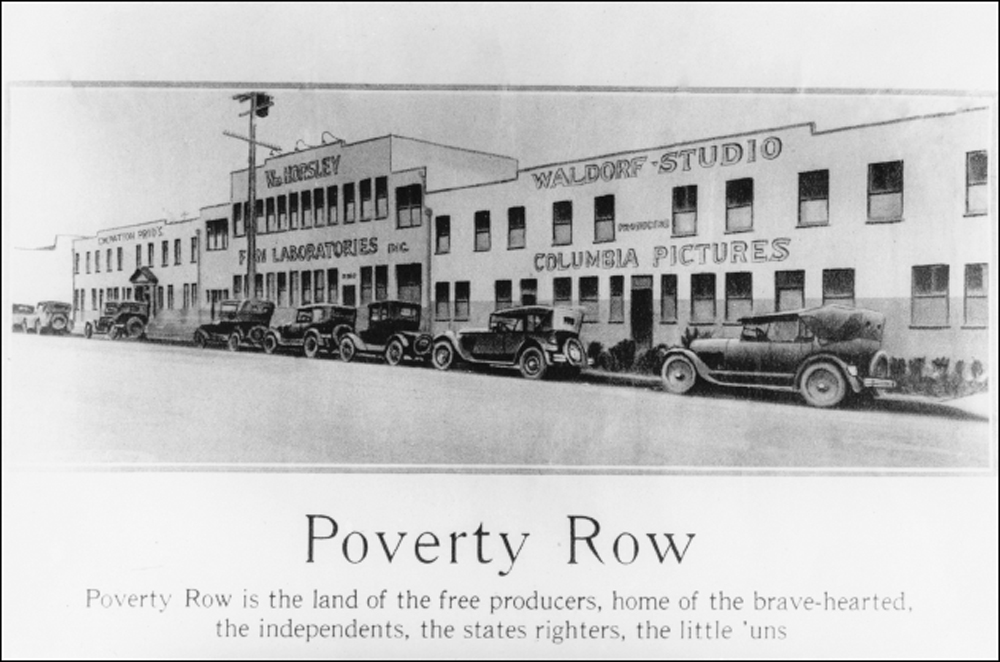

POVERTY ROW STUDIOS, 1925. Rather than avoid the disparaging nickname Poverty Row, early producers chose to embrace it, as is evident from this 1925 advertisement, which proclaims that Poverty Row is the land of the free producers, home of the brave-hearted, the independents, the states righters, the little uns. Depicted in this drawing are, from left to right, C.W. Patton Productions at 6050 Sunset Boulevard, the William Horsley Laboratory at 6060 Sunset Boulevard, and the Waldorf Studio at 6070 Sunset Boulevard. Waldorf was the birthplace of Columbia Pictures, proving that sometimes the little uns got big. (Courtesy Bison Archives.)

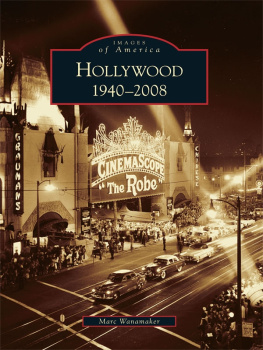

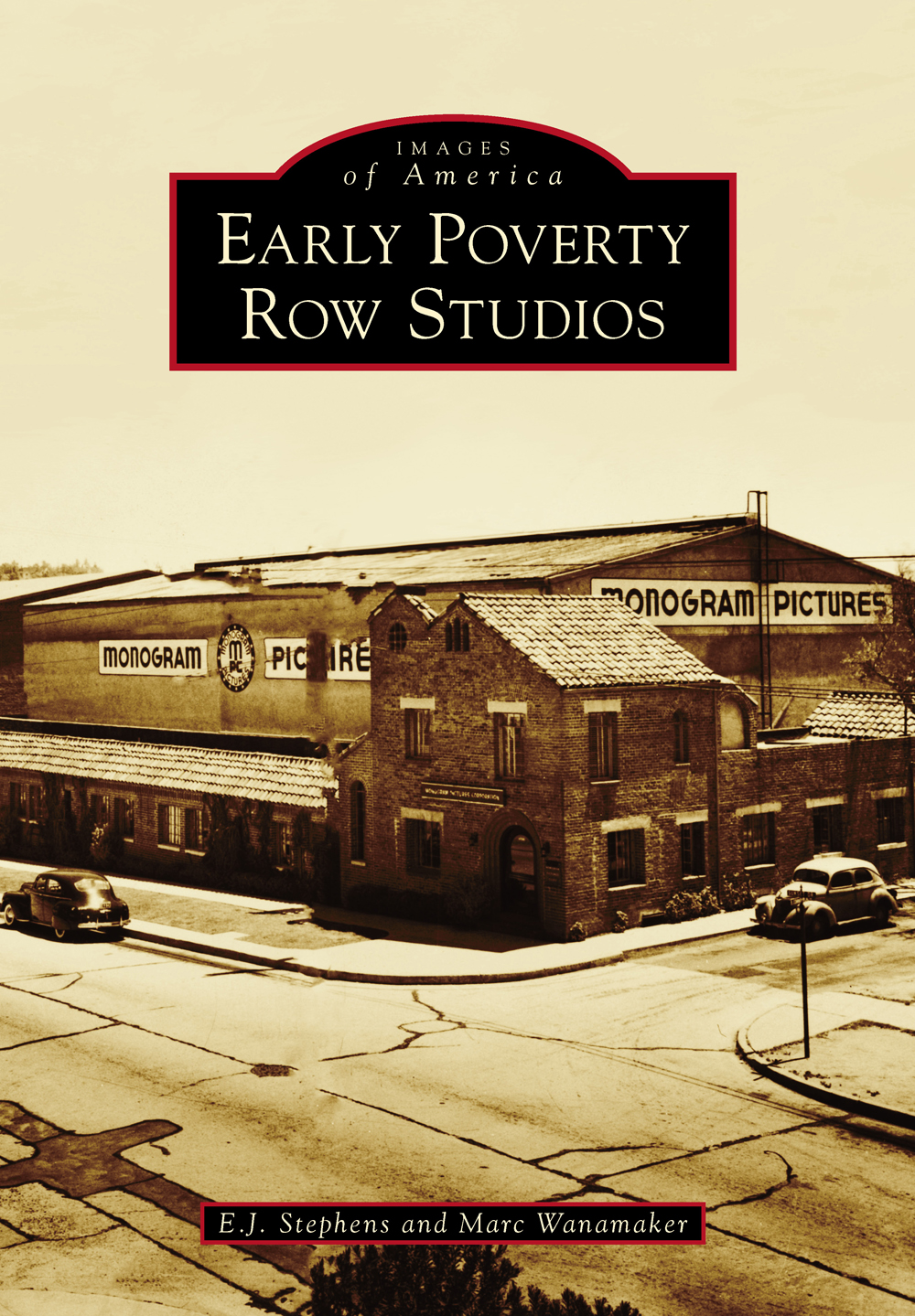

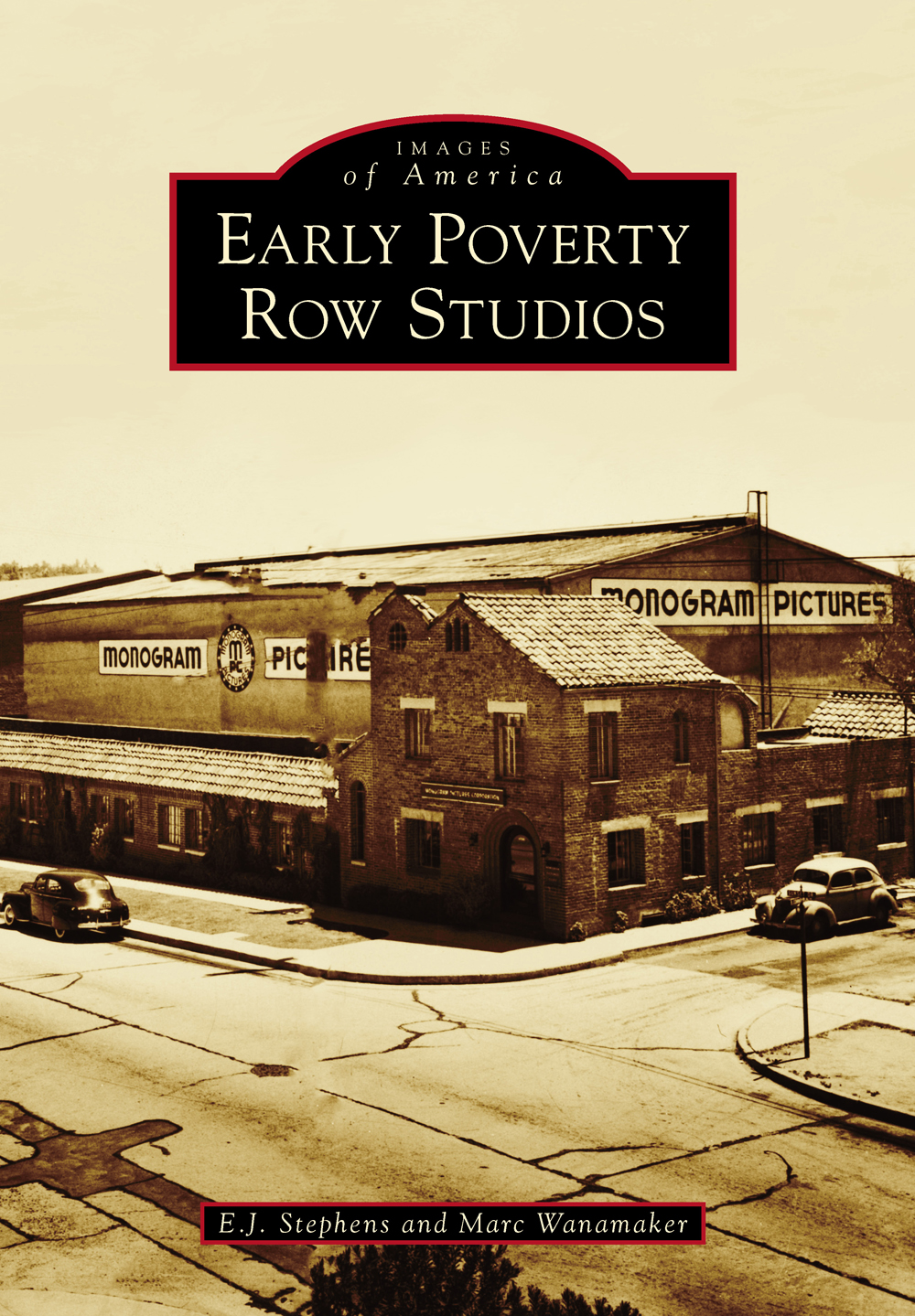

ON THE COVER: MONOGRAM PICTURES, 1941. One of Poverty Rows best-known tenants was Monogram Pictures, created in the early 1930s through the merger of Trem Carrs Sono ArtWorld Wide Pictures and W. Ray Johnstons Rayart Productions. Monogram was famous for its low-budget Westerns and for the Monogram Nine, a collection of horror films starring Bela Lugosi. For two years in the mid-1930s, Monogram was part of Herbert Yatess Republic Pictures before again going independent. (Courtesy Bison Archives.)

IMAGES

of America

EARLY POVERTY

ROW STUDIOS

E.J. Stephens and Marc Wanamaker

Copyright 2014 by E.J. Stephens and Marc Wanamaker

ISBN 978-1-4671-3258-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439648292

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014941231

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

Dedicated to the thousands of early cinematic pioneers, who took a chance and changed the world

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank everyone at Arcadia Publishing for their hard work, especially our editor Jared Nelson.

E.J. would like to thank Marc Wanamaker for his passion, his encyclopedic knowledge of early Hollywood, and his priceless Bison Archives collection. He would also like to thank his good friend Steve Goldstein, who, along with Theodore Hovey of Hollywood Forever Cemetery, helped him right an old wrong by finally getting Ford Sterlings crypt marked. But mostly, he thanks his beautiful wife, editor, and soul mate, Kimi, who reminds him with every glance that he is the luckiest man alive.

Marc Wanamaker would like to thank E.J. Stephens for helping him put this book together and for his excellent writing skills. He would like to thank his late mother, Edith Wanamaker, for helping him catalogue his collections over the years (before computers), organizing voluminous amounts of information culled from countless sources.

Thanks also go to Robert S. Birchard for the use of photographs and for his research on early motion picture companies. Major thanks to Hollywood Heritage, who helped preserve the Lasky- DeMille Studio Barn. Thanks to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for its Margaret Herrick Research Library. Others who contributed to the photographic research and information include Michael Peter Yakaitis, Tommy Ryan, Mike Hawks, Linda Mehr, Matt Seversen, Cecilia DeMille Presley and Helen Cohen of the Cecil B. DeMille Estate, Kevin Brownlow, George Pratt (formerly of the Eastman House), Ray Stuart, Larry Edmunds Bookshop, Howard Mandelbaum of Photofest in New York, Movie Star News, UCLA Archives, USC Archives, American Film Institute Library, University of Madison Wisconsin, Georgetown University Archives, Andy Lee of the Universal Research Library, Jimmy Earie of the MGM Research Library, Lillian Michelson of the Goldwyn Research Library, Ken Kenyon of the 20th Century Fox Research Department, Kellum DeForest of the RKO Research Library, Fred Jorden of Producers Studio, the Rosenthal family of Raleigh Studios, Bill Kenly of Paramount Publicity in New York, Jack Warner Jr., Universal Old Timers Club, Hal Roach, Brent Christo, Dick Bann, British Film Institute Archives, Bruce Torrence, Dino and Greg Williams, Jesse Lasky Jr., Cinemabilia of New York, Collectors Bookshop in Hollywood, Mary Corliss of the MOMA in New York, John Kobal, and many others. All information and photographs are courtesy of Bison Archives.

INTRODUCTION

In the first decade of the 20th century, Hollywood was still miles from the encroaching city of Los Angeles, cattle herds ambled down unpaved Sunset Boulevard, and the marketing of demon liquor was strictly verboten.

It was at this time that the first wave of West Coast cinematic pioneers stepped into this obscure hamlet, where initially film crews were as unwelcome as blight on the vineyards bordering Vine Street.

Many settled around the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street at an area that came to be known as Poverty Row. It was here, before the rise of the major studios, that an industry of light and movement secured its first toehold in Hollywood.

During this era, Poverty Row was a catch-as-catch-can kind of place, where most producers lived from film to film, feasting or failing based on the take from hundreds of nickelodeon tills scattered throughout the country. Most of these start-ups folded or were absorbed by larger concerns, but a few, namely Warner Bros. (WB) and Columbia, took root, prospered, and are still with us today.

But for every WB or Columbia, there were dozens of other production houses that came and went along Poverty Row, with names like L-KO Motion Picture Company, Amalgamated, Russell Productions, Century Film Corp., Christie Studios, Harry Joe Brown, Crown, Norman Dawn, Goodman, Goodwill, Granada, Hutchison, Morante, Ben Wilson, Kinemart, Phil Goldstone, Bud Barsky, Bischoff/California, Big Chief, Color Craft, Charles J. Davis, Gold Medal, Pacific Pictures, and Yaconelli Productions, to name just a few.

Over time, Hollywood became more of a conceptual term than a geographic one, as most of the Hollywood movies made throughout history came from studios located in places like Burbank, Glendale, and the film citiesStudio City, Culver City, Century City, and Universal City.

The same can be said for Poverty Row, which was stretched to include producers from other places around Los Angeles whose own struggle to hang on to the Hollywood landscape was often a story more intriguing than the plots of the serialized cliffhangers that many produced.

In the early 20th century, Hollywood was much like dozens of other rural hamlets sprinkled throughout Southern California, known for its mild Mediterranean climate, ample agriculture, varied vistas, and 350 days of sunshine a year. It was a snobby town, unfriendly towards film people and their creations.

The area had been Mexican territory just a few decades earlier until the treaty that led to it becoming American soil was signed in 1847 at what is today the entrance to Universal Studios. The future film capital was a rich agricultural area 40 years later when teetotaler Harvey Wilcox and his young bride, Daeida, purchased a 160-acre parcel of farmland with the intention of subdividing it for residents of their planned temperance community.

The region was well known at the time for its figs, citrus, melons, avocados, and grapes, but two products that it did not produce in abundance were holly, which would not take to the soil, and wood, since the land was unforested and covered by chaparral. The genesis of the name came during a train trip Daeida Wilcox took where a female passenger told her about a summer home she owned named Hollywood back in the eastern part of the United States. Liking the name, Wilcox penned it to the new settlement, forever linking the name of an unknown vacation home with the mythical industry of image.

Next page