THE WANDERING YEARS

1922-1938

Cecil Beatons Diaries

Volume One

To the Memory of my Father

And tell of time, what gifts for thee he bears.

What griefs and laughter through the wandering years.

Euripides, Bacchae

Table of Contents

Foreword to the New Edition

I welcome the republication of the six volumes of Cecil Beatons diaries, which so delighted readers between 1961 and 1978. I dont know if Cecil himself re-read every word of his manuscript diaries when selecting entries, but I suspect he probably did over a period of time. Some of the handwritten diaries were marked with the bits he wanted transcribed and when it came to the extracts about Greta Garbo, some of the pages were sellotaped closed. Even today, in the library of St Johns College, Cambridge, some of the original diaries are closed from public examination, though to be honest, most of the contents are now out in the open.

The only other person who has read all the manuscript diaries is me. It took me a long time to get through them, partly because his handwriting was so hard to read. I found that if I read one book a day, I had not done enough. If I did two in a day, then I ended up with a splitting headache! This in no way deflected from the enormous enjoyment in reading them.

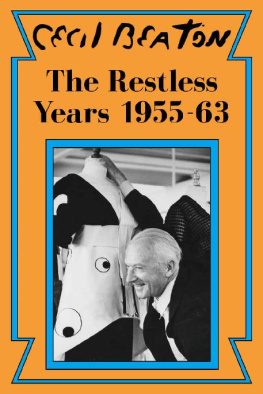

Altogether there are 145 original manuscript diaries dating from Cecil going up to Cambridge in 1922 until he suffered a serious stroke in 1974. A few fragments of an earlier Harrow diary survive, and there is a final volume between 1978 and 1980, written in his left hand. 56 of these cover his time at Cambridge, some of which appear in The Wandering Years (1961) . 22 books cover the war years, and were used for The Years Between (1965), and nine books record his My Fair Lady experiences, some of which appear in The Restless Years (1976) and were the basis for Cecil Beatons Fair Lady (1964). These six volumes probably represent about ten per cent of what Cecil Beaton actually wrote.

The diaries attracted a great deal of attention when first published. James Pope-Hennessy wrote of Cecils thirst for self-revelation, adding that the unpublished volumes were surely the chronicle of our age. Referring to Cecils diaries, and those of Eddy Sackville-West, he also commented: We could not be hoisted to posterity on two spikier spikes.

I have to tell the reader that these volumes were not always quite the same as the originals. Some extracts were rewritten with hindsight, some entries kaleidoscoped and so forth. Certain extracts in these six volumes were slightly retouched in places, in order that Cecil could present his world to the reader exactly as he wished it presented. And none the worse for that.

Hugo Vickers

January 2018

Introduction

It isnt easy to make public the private record of a lifetime. Of all forms of writing, diaries are the most personal; their publication cannot but invoke question or criticism.

Most mysterious is why people write them. Someone once commented to me, I always mistrust people who keep diaries. I winced and was set to wondering. Had I scribbled hundreds of volumes out of boredom, loneliness, frustration or the need for self-assertion?

Perhaps; but my obsession also stemmed from those same obscure motives that have impelled me to take snapshots all my life. Even as a child I felt haunted by a sense of the elusive. And when I grew up, carpe diem became my watchword. I exposed thousands of films, wrote hundreds of thousands of words in a futile attempt to preserve the fleeting moment like a fly in amber.

Hence perhaps the existence of these pages. They are winnowed from an exhaustive record in which anything and everything was set down. But does that justify their publication especially when the most private events are described? I shall inevitably be charged with over-zealous candour. Why, my critics will ask, didnt I hide the diaries under the floorboards?

Reply is not easy. There is, of course, the precedent of other diarists who published journals in their own lifetime. But they have been men of letters, adventurers, generals or statesmen. My province is more frivolous, as my critics never cease to remind me. But perhaps for that very reason I may unwittingly have captured fragments of a social scene that might be shared and give a certain nostalgic amusement to others.

If I am at times too candid, it is not by design but because indiscretion is almost unavoidable: individual idiosyncrasies are more dangerous to deal with than the events of a military campaign or an intrigue in Arabia. In any case, the reader will find I have spared myself no more than others. I find it painful to reveal myself as I was. This is scarcely a flattering self-portrait. Yet truth begins with ones self. No attempt has been made to touch up those extracts in which I appear in a particularly unsympathetic light: for they, too, help to give a picture of the time. I hope, however, that the reader will bear in mind the social circumstances that formed me. In terms of todays more relaxed manners and disregard of conventions, the opinions or attitudes of a young Englishman of years ago must inevitably seem preposterous.

But I must not protest too much. Let the diaries speak for themselves. Their content remains unaltered, though from time to time I have fused a number of entries to form a single recollection of a person or a place. Readers may complain that too much space has been given to a description of an unimportant occasion, whereas some other event that must have been of consequence to me has been indicated in a couple of lines or entirely ignored. But surely this is the very nature of most diaries? In any event they are apt to give a lop-sided impression, since the writer generally does most of his work when feeling melancholy, lonely or down on his luck. Hence the general picture is often self-pitying, or gloomily introspective.

I have tried to fill in the more serious lacunae with narrative comments not so much to give an autobiographical form to the volume as to explain certain extracts that might otherwise be obscure or in need of a longer context. The story told here begins at Cambridge and ends with the outbreak of the Second World War.

CECIL BEATON

Part I: Cambridge, 1922

After three escapist years at Harrow School, where my fledgling interests were ex-curriculum, and any signs of intelligence were seen only out of class, my father was faced with the problem of what to do with me. Most of my contemporaries now knew what they wanted to be in life; but at the age of eighteen I showed no particular aptitude for any known career. I had acquired somewhat of a reputation, and a certain amount of scandalous disapproval, for being able to make people laugh, and was considered sophisticated for my age. Yet I was, in many ways, remarkably undeveloped. It is true that I had been the art masters prize pupil, with a knack for water-colour sketches, and a derivative flair for caricature and theatre design; but I, myself, had little confidence in these talents. In fact, secretly I was as anxious about my future as my father must have been.

It was therefore a welcome reprieve when my parents decided that my education should be continued at a university. Most parents already knew to what university, and to which college their offspring were to go. But my father was delightfully casual about such things, and one Saturday afternoon, at the thirteenth hour, set off at the wheel of the family Renault for Cambridge. Here he interviewed a Mr Armitage of St Johns college. It is only now, so many years later, that I understand what a remarkably generous and loving parent I was fortunate enough to have. Perhaps too close a proximity prevented his children from seeing him as the wistful and rather whimsical person he was; and with the years he wore a sad expression that may have been the result of feeling unappreciated. When, however, he came across some stranger who reacted to his charm or his wit, his whole being changed, and he shone brilliantly. My father had been all his life an enthusiastic cricketer and was, in fact, renowned as a wicket-keeper.

Next page