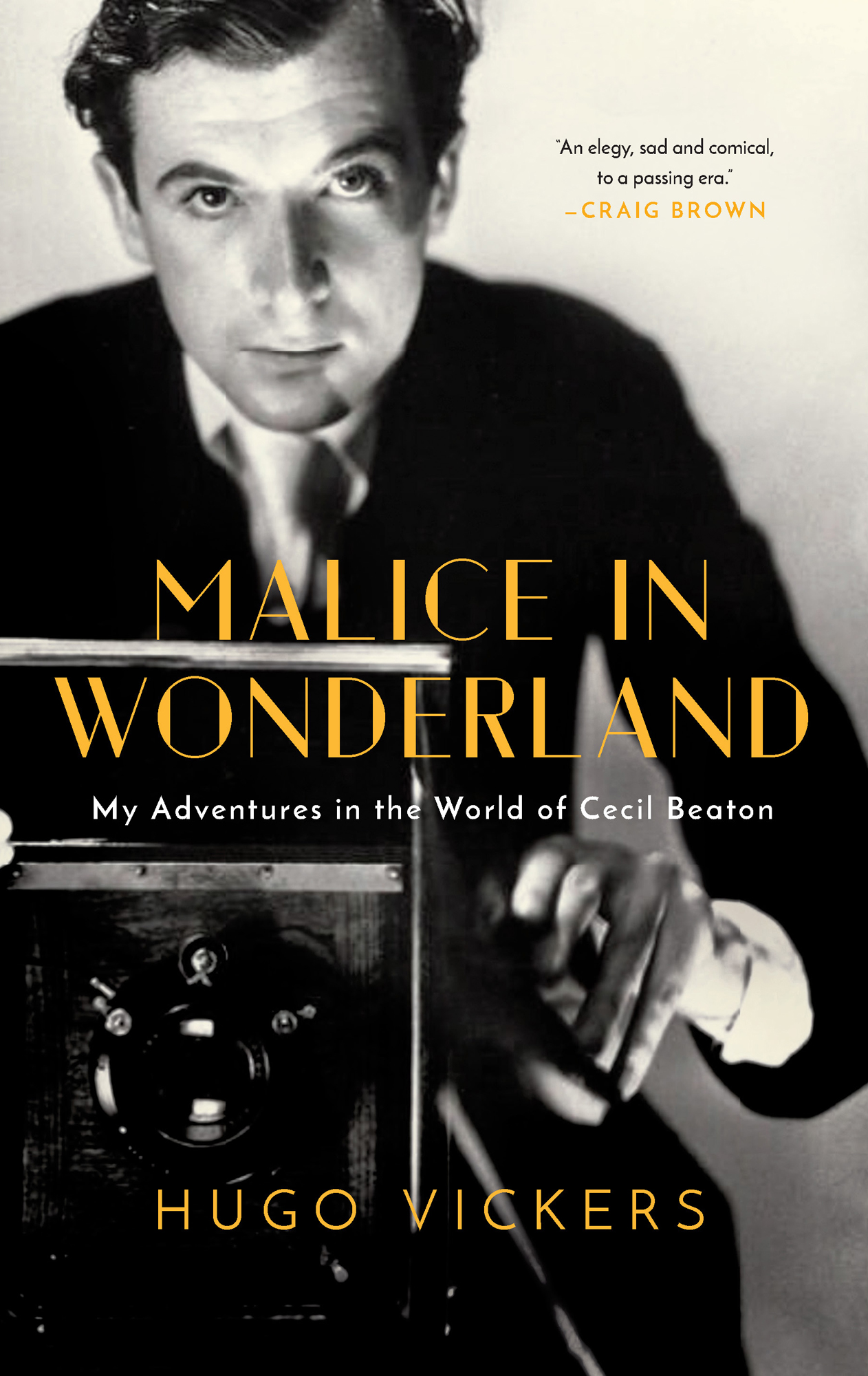

An elegy, sad and comical, to a passing era.

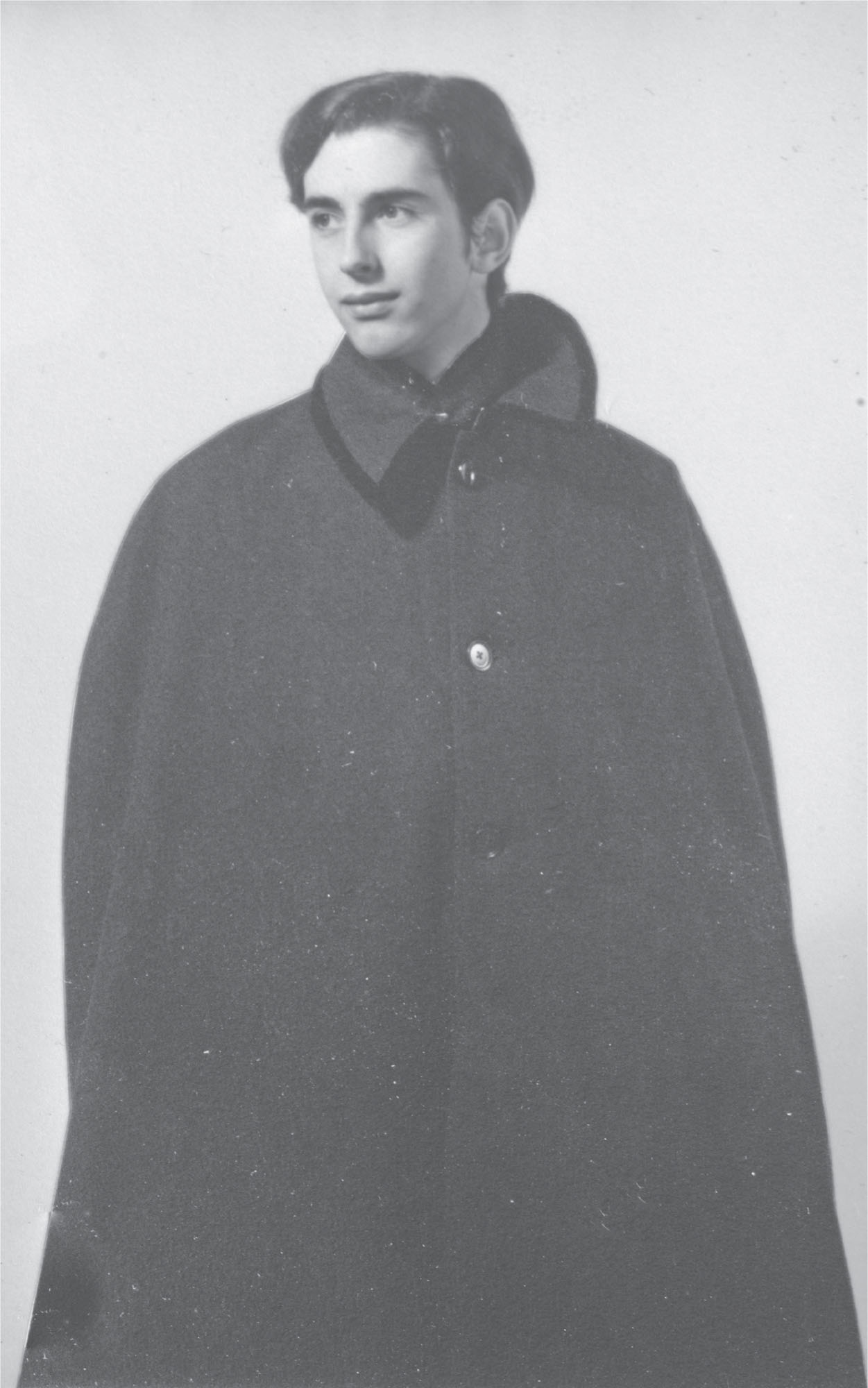

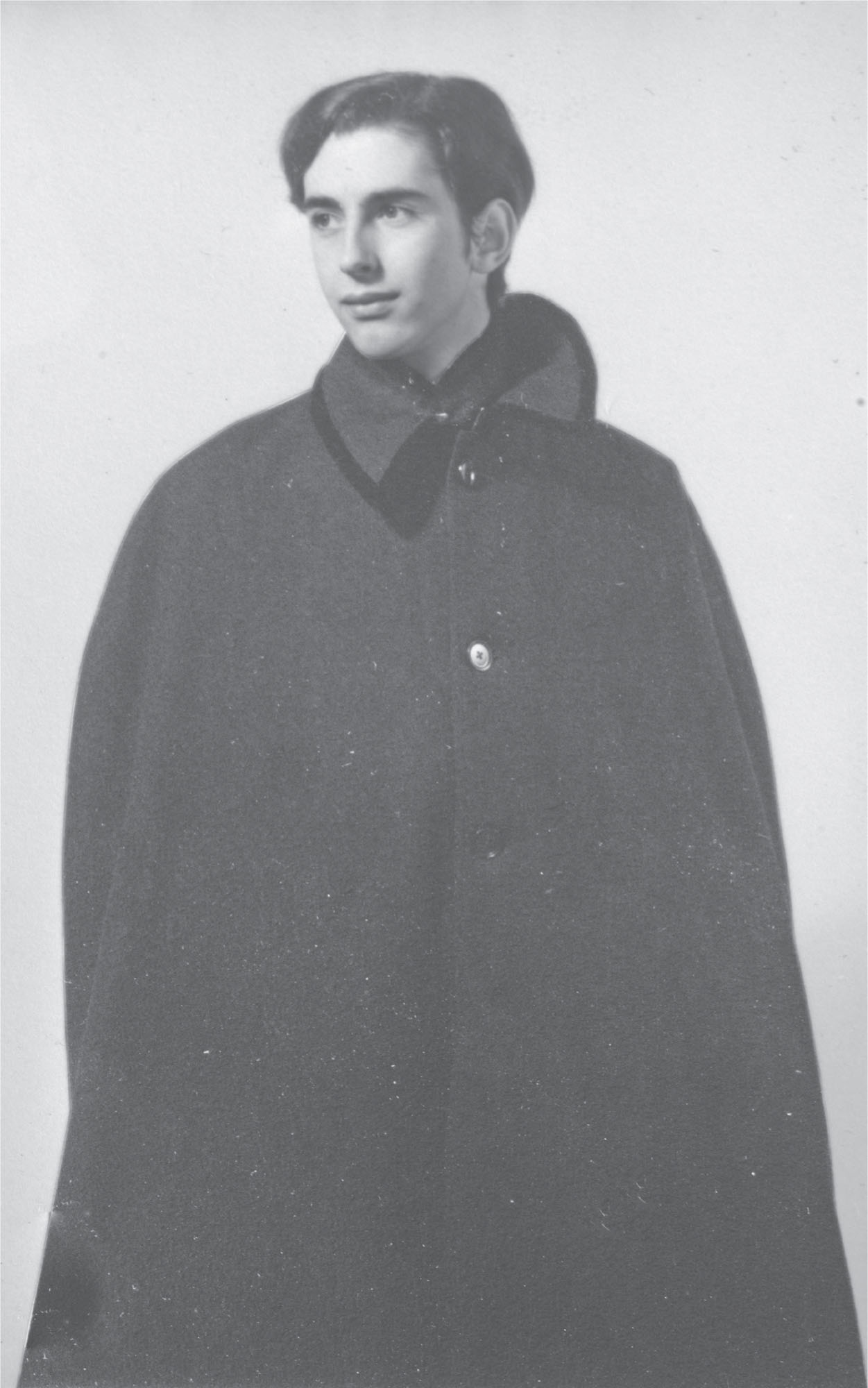

Me in a Cecil Beaton pose, 1969

Introduction

The vision of the past is a dream, a long-drawn sunset splintering into a thousand fires. Edith Wharton gave me that line, but it echoed in my head as I looked back over the years I spent walking in the footsteps of Cecil Beaton. In the long weeks of lockdown, it was a great joy to open the safe and pull out diaries written forty years ago to relive an exciting adventure my good fortune to have been given a passport into a magic world quite new to me. A lost world came to life as I reread my youthful notes the excitements, the setbacks, the extraordinary people, the occasional sense of being overwhelmed by the task of doing justice to a man of so many parts. It led to authors whose books I had never read but then devoured with glee, to meetings with stars from childhood, who had seemed impossibly beyond my orbit. It sharpened my visual taste and I, who only bought books, now bought pictures.

I have said many times that for Cecil Beaton every day was a birthday, every afternoon a matine, the red velvet curtains opening on a new set, every evening a first night, champagne waiting in the wings. He lifted people out of humdrum worlds and gave them something to dream about.

I did not feel that my world was particularly humdrum, but I had emerged from a long, life-changing adventure in my quest for Gladys Deacon. If she had been the first person to breathe life into me and make me think in a different way, then Cecil Beaton guided me (albeit posthumously) into a PhD in lifestyle, new values, new experiences, new challenges.

For several weeks in those long, essentially glorious summer weeks of 2020, I went back into a lost world and lived it once more.

This book is based on the private diaries I kept during those years some fifty-one handwritten books, covering the years between 1979 and 1985. They represent a fraction of what was written, there having been 240,000 words on the work into the biography, excluding anything more personal or irrelevant.

I had started keeping a full diary in 1975, when I was researching Gladyss life. I found I was being told things that were interesting sometimes even historically important which would not fit into the biography. Diary writing is a good exercise for a biographer, turning daily happenings into the written word, a bit like practising daily at the keyboard for a pianist. Diaries are particularly interesting as, unlike the historian or biographer, the diarist does not know what is going to happen next. Here was a chance to record my progress, or lack of it, the excitements and disappointments. My diary was my friend, good therapeutic company on my journey.

Perhaps inspired by James Pope-Hennessy and his notes on Queen Mary, some of which I read at about this time, I wanted to record raw what the sources told me, not all of which found its way into the published biography what I thought of them, what they said about each other and how I started on the outside and was quickly scooped into their world.

These pages do not include the other things going on in my life at this time. The extracts focus on the work and on the characters in Cecils world.

- . Gladys Deacon (18811977), a beauty and intellectual, who dazzled the salons of Europe, became the second wife of the 9th Duke of Marlborough in 1921, and spent her later years as a recluse.

- . Gladys, Duchess of Marlborough, reissued as The Sphinx in 2020.

Authors Note

I appreciate that the world in 2021 is a different place from what it was in the 1980s. My diaries reflect and record what was said at the time, but the world of Cecil Beaton was one where both the public and private understanding of sexuality was sometimes confused and contradictory. The people I spoke to discussed this openly, and the way they expressed themselves in those far-off days was frequently different to what is now considered acceptable. This potentially difficult material has been left in, however, as they are inextricable from Beatons life, his social circles and my experiences and conversations during this period of time.

The Quest Begins

One telephone call changed my life completely. On 4 December 1979, I was sitting at home when John Curtis, I was then under commission to write a joint biography, a plan eventually dropped.

I had not lobbied to write about Cecil: I did not know a biography was being planned. But there was not an instant of hesitation. I set off on a journey that would last over five years and take me into some unusual situations, and into worlds I had never dreamt of. Nothing would ever be the same again.

As for me, in the days before the telephone call, I had paid a long overdue visit to the two Kappey sisters who later featured in my book The Kiss. I had tidied up a proposed book for Debrett about Prince Charles (held back until it could be a royal wedding book). On the day before, I had written an article for Tina Brown, then editing Tatler. That night I had gone to a party of intolerable boredom given by Debrett. A man there held a cigarette in a way that the smoke went directly up my nose. I moved back; he moved forward it was a sinister sort of dance. I tried to escape his wretched conversation about family trees. I had dinner with a French friend in a restaurant and told her: I see little point to life these days. The next day John Curtis rang.

I did not come from a family of writers, though reading was always a feature of my home. My father was a successful stockbroker. Unfortunately I have no head for figures and would have made a hopeless City man. It was my mother who encouraged me to follow my own path. She was a great admirer of Cecil Beaton, and when I was fourteen I stole her copy of his The Glass of Fashion. In 1964 she took me to see My Fair Lady, for which he had designed the costumes, towards the end of its run at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Zena Dare was still in the cast, though Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews had long moved on.

In 1968 I had gone alone to Beatons National Portrait Gallery exhibition, and in 1971 to his fashion exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. I had seen him in life when he arrived with Lady Diana Cooper at the funeral of the Duke of Windsor at St Georges Chapel in May 1972, and when he attended a performance of