TO THE MEMORY OF REX WHISTLER

Table of Contents

Foreword to the New Edition

I welcome the republication of the six volumes of Cecil Beatons diaries, which so delighted readers between 1961 and 1978. I dont know if Cecil himself re-read every word of his manuscript diaries when selecting entries, but I suspect he probably did over a period of time. Some of the handwritten diaries were marked with the bits he wanted transcribed and when it came to the extracts about Greta Garbo, some of the pages were sellotaped closed. Even today, in the library of St Johns College, Cambridge, some of the original diaries are closed from public examination, though to be honest, most of the contents are now out in the open.

The only other person who has read all the manuscript diaries is me. It took me a long time to get through them, partly because his handwriting was so hard to read. I found that if I read one book a day, I had not done enough. If I did two in a day, then I ended up with a splitting headache! This in no way deflected from the enormous enjoyment in reading them.

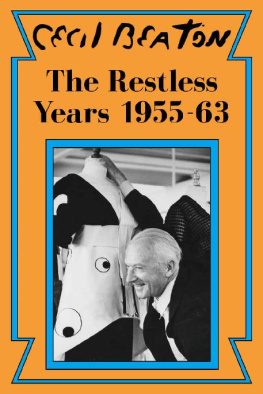

Altogether there are 145 original manuscript diaries dating from Cecil going up to Cambridge in 1922 until he suffered a serious stroke in 1974. A few fragments of an earlier Harrow diary survive, and there is a final volume between 1978 and 1980, written in his left hand. 56 of these cover his time at Cambridge, some of which appear in The Wandering Years (1961) . 22 books cover the war years, and were used for The Years Between (1965), and nine books record his My Fair Lady experiences, some of which appear in The Restless Years (1976) and were the basis for Cecil Beatons Fair Lady (1964). These six volumes probably represent about ten per cent of what Cecil Beaton actually wrote.

The diaries attracted a great deal of attention when first published. James Pope-Hennessy wrote of Cecils thirst for self-revelation, adding that the unpublished volumes were surely the chronicle of our age. Referring to Cecils diaries, and those of Eddy Sackville-West, he also commented: We could not be hoisted to posterity on two spikier spikes.

I have to tell the reader that these volumes were not always quite the same as the originals. Some extracts were rewritten with hindsight, some entries kaleidoscoped and so forth. Certain extracts in these six volumes were slightly retouched in places, in order that Cecil could present his world to the reader exactly as he wished it presented. And none the worse for that.

Hugo Vickers

January 2018

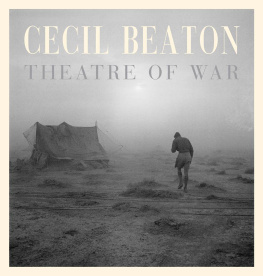

Part I: Ashcombe , 1939-40

September 1939, Ashcombe, Tollard Royal, Wiltshire

I feel frustrated and ashamed. This war, as far as I can see, is something specifically designed to show up my inadequacy in every possible capacity. I am too incompetent to enlist as a private in the army. Its doubtful if Id be much good at camouflage in any case my repeated requests to join have been met with, Youll be called if youre wanted. What else can I do? I have tried all sorts of voluntary jobs in the neighbourhood, helping Edith Olivier organize food control, and the distribution of trainloads of refugee children from Whitechapel. I failed in a first aid examination after attending a course given by a humorous and kindly doctor in Salisbury. Now I start as night telephonist at the ARP centre in Wilton.

September 18th

Our squad is on duty from eleven at night until 8 a.m. On arrival at ugly, Victorian-Gothic, Fugglestone House, we study maps of the vicinity and check our individual tasks. But we all express the hope, for more reasons than one, that there will be no air raid tonight. We have been only rather vaguely briefed in our duties; at the sign of an alarm I am bound to get hopelessly entangled with all the various wires and plugs at the switchboard. Mr Lush, the Town Clerk, is here in case we need help, and Mr Keating, a retired civil servant, is our rather quavering lead. We are an odd assortment and I fear not of marked efficiency, all tweed clad, and country folk (except myself), with rugs, top boots and thermoses of cocoa and Bovril. There are two gentlemen farmers from nice grey stone houses in the neighbourhood, and a grey, hatchet-faced, older woman with a balloon-cheeked debutante daughter. Lady Pembroke, her face drained white, has come across from the big house in grey flannels and heavy overcoat, accompanied by Smith, the Pembroke butler, lobster-coloured, deep-voiced and with perhaps enough ballast to keep our whole group afloat. During the watch he sits quietly, imbibing a crackling pipe and blinking in front of him. When, at early dawn, the switchboard gives us a false alarm, Smith, although dozing at the time, is the first to be on the spot.

Grouped together in this room, reinforced against blast with stanchions of rough wood and sand-bags and curtained with the heaviest felt, we gradually settle down to read, the women to sew; each has a turn to be on a truckle bed for an hours sleep. It is a boring, dispiriting job, and it is difficult to find volunteers to fill it. We are resigned to be together for the duration of the war; a pretty grim prospect.

I lie listening to the others talking. They have the friendly easy personalities that you find only in the countryside. Full of human sympathy, they have a stolid sense of the humorous. They know how to be serious too, and when discussing politics are not ashamed of a clich.

After midnight the radio is silent, but for the whispering sounds it gives out, like those of a peat fire.

Another hour to go. As I sit on the window-sill watching the others staring at mental pictures of war deprivations, cold, and general cheerlessness, my esteem for them is very high. It hurts almost as much to muse upon pain as to endure it. These civilians are suffering the anticipation of wounds to those they love the most. How gallant they are! Yet in the early grey dawn how much older and greyer they appear. Even the pullet-like debutante has grown overnight to maturity, and Captain Myddelton has become like an actor who, in the last act, puts on a grey wig and must appear thin in his clothes and walk with a stiff gait. Dear old Mr Keating, wrapped in a fishing coat, is suddenly a little Methuselah.

Noises of heavy boots and whistling come from the rooms above. Down the carpetless stairs the fire brigade and first aid squad return to duty. The first night of the watch is over.

December 3rd

It is just three months since that Sunday morning when, at 11.15, here, in this small sitting-room, the radio told us that we were at war with Germany. Slow tears trickled down my mothers cheeks on to the needlework rug she was making: every time I look again at those pictures I was pasting into an album I hear again Mr Chamberlains pewter-grey voice.

The radio became the focal point of all our days. Each bulletin brought more news than we had known in a decade. Yet the catastrophe we braced ourselves to face did not happen; a quiet stalemate was achieved on the Western front and the undramatic weeks of waiting were perhaps the dreariest of all our lives a numbing continuation of anxiety and boredom. Like states of ill health we fortunately forget the mental anxieties through which we pass. By degrees weve accustomed ourselves to the fact that we are at war and try to go on leading our own ordinary existences as best we can.

Blackout material is now tacked to the orange and yellow striped curtains, one of the wall-lights flickered on the blink and then went out. Since Graham, the manservant, got a job in the Air Ministry, and with Mrs Graham, her cat in her arms, has bidden us farewell, there is no one to mend it. The front door bell is also broken.