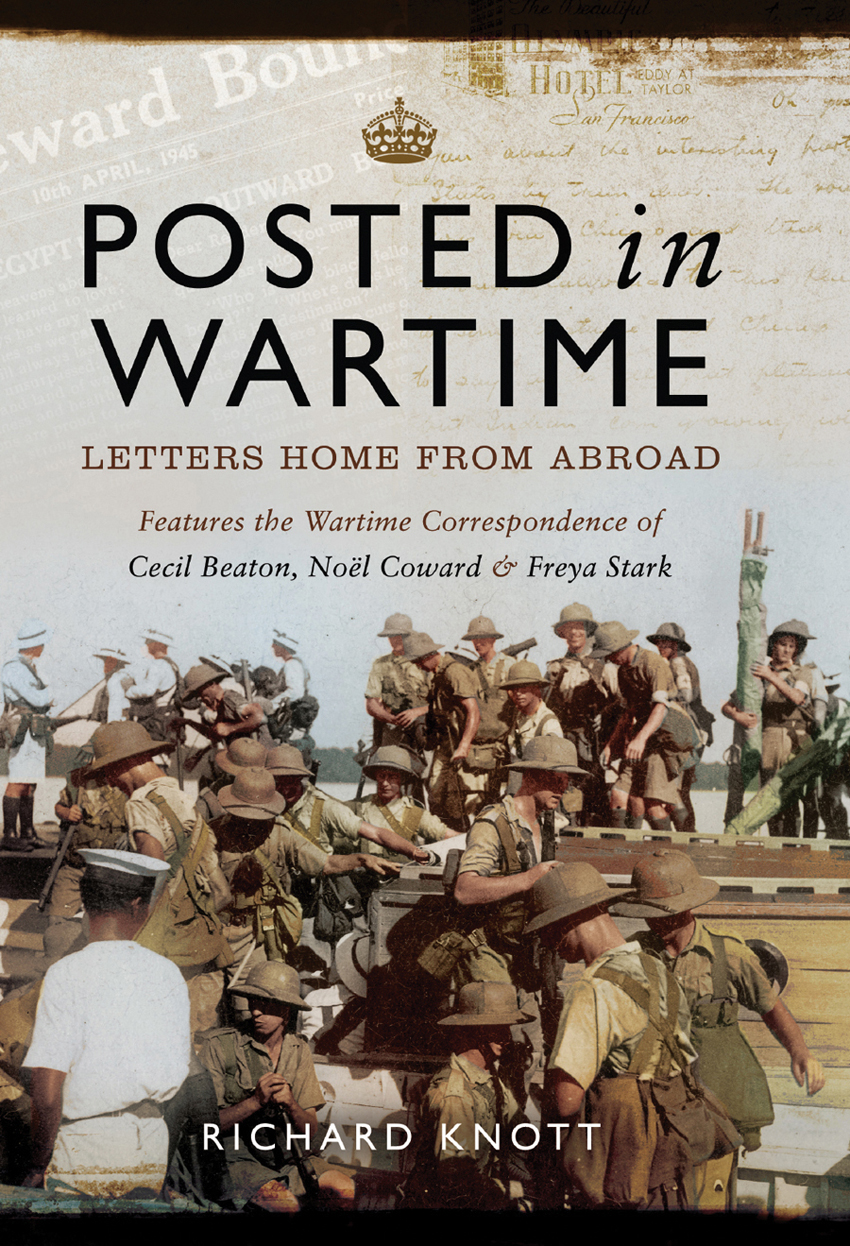

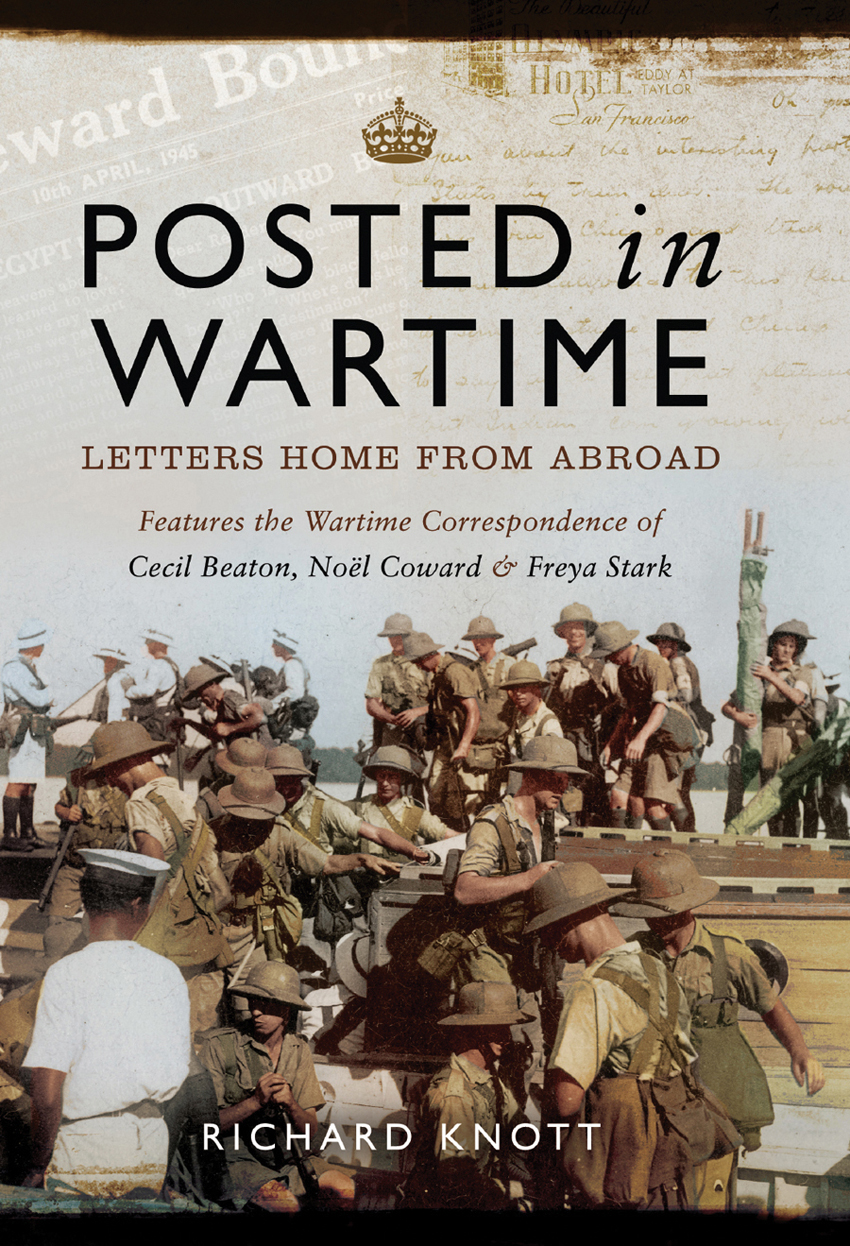

Posted in Wartime

For Julia Martina Knott

Posted in Wartime

Letters home from abroad

Richard Knott

Featuring the wartime correspondence of Cecil Beaton, Nol Coward and Freya Stark

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard Knott 2017

ISBN 978 1 47383 396 8

eISBN 978 1 47388 441 0

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47388 440 3

The right of Richard Knott to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Exile is an illness an illness of the mind, an illness of the spirit and even sometimes a physical illness.

Lara Feigel, The Love-Charm of Bombs

After a bad war, Ive read, the officers stammer and the ranks become mute.

Annette Kobak, Joes War

Here I am in the Army and I think Im going to have a fine time, war permitting.

Gunner John Syd Croft, Royal Artillery

Chapter 1

Keep Me Posted

When this war started, I suddenly found myself totally unable to write letters. I dont know why. I suppose I had the feeling that they would never get to their destination. But now the post does seem to be working, if a bit spasmodically. I expect youll get this in about ten days.

P.G. Wodehouse to William Townend, Le Touquet, Pas-de-Calais, 3 October 1939

I do so hope it wont be like being in cargo ships where I didnt get a letter from one voyages end to another. Your letters are about all I have to look forward to.

Tommy Davies to his wife Dorrie, at sea on board Almanzora , 23 April 1942

You will write, wont you? How many times in the last precious moments of a wartime lovers farewell did one or other of the soon-to-be-parted ask such a question, or breathe a promise that he or she would write? Such promises were all the more fervent, perhaps, when the prospect was of a posting far from home: you would not expect exile to be endured in a glum silence. And yet there is no evidence that my father wrote anything in his four wartime years away in the Middle East, at least, nothing that merited keeping. Added to which was the fact that he would never talk about the war at all. Those two connected mysteries are central to this book.

The mystery of my father Jack had a way of shifting like quicksand as I wrote. For example, I had always believed that he was a bespoke tailor before the war, living in the English Midlands, an ordinary man plying an unremarkable trade in one of Englands less green and pleasant towns. More than six years after he died, the publication of the 1939 Register revealed him to be a Forge Labourer. Shell Factory. It was, dare I say it, a bombshell. That revelation did not, however, alter the basic question: how different, I wondered, would his overseas service have been from others like him; and, more tellingly perhaps, how much of a contrast would the experience of the more celebrated have been in similarly distant situations? At much the same time as I was contemplating that comparison, I was loaned substantial bundles of letters written by two men whose war involved long journeys and prolonged absences from home. Their evidence begged the question that would not go away: why would some write at such length while my father seemingly remained so silent? Those letters and my fathers reluctance to communicate comprise a major strand in this book. Woven into that story are the wartime experiences of three celebrities for whom the war also meant periods of exile: the photographer and designer Cecil Beaton; the playwright Nol Coward; and the traveller and writer Freya Stark.

Wartime exile is a key theme in this book; it is what connects the six principal characters, both the celebrated and the unknown. Posted in Wartime has a double meaning, of course: the first of which refers to the role and nature of written correspondence during the war the impact, for example, of censorship and stretched lines of communication, the slow and unreliable postal service on which those sent abroad relied for news and reassurance. Even, presumably, my tight-lipped father. The second meaning concerns the despatching of individuals to far corners of the world, sent hither and thither to fight, police, drive transports, administrate, liaise, or entertain. That process was often the result of some anonymous civil servants whim or staff officers hunch, which duly consigned someone to a rattling, cold Liberator or DC3, or a transcontinental train; or, more likely, some rusty troopship beating its way from one fly-blown port to another. There was no choice in the matter: the teacher and author Charles Hannam, for example, who had arrived in Britain on one of the last Kindertransport trains, decided late in the war to defer a place at Cambridge to sign on to join the fight against Hitler; he was posted instead to Burma and then India to police the transition to independence.

And why the choice of Beaton, Coward and Stark? Why those three representatives of the more celebrated and fortunate? I was increasingly drawn to the fact that all three undertook wartime journeys whose trajectories crisscrossed and intertwined with those of my three unknown soldiers. These comprised Tommy Davies, an officer in the Merchant Navy; an army doctor, Donald Macdonald; and my father Jack, an RAF policeman. All six, like so many others, were being moved like chess pieces around the board; never in a position to feel they had finally arrived, with no sense of permanence.

* * *

At some point in the war my father and his brother-in-law George Moreton bumped into each other in Alexandria Jack would periodically complain thereafter that he had never recovered the pound note my uncle borrowed on that sun-baked Egyptian street. It was a typical wartime encounter, one of many where the logistics of a global conflict turned certain places into transport hubs, busy crossing points, where you stood every chance of meeting a relation, or an old friend, in what might once have been thought the most unlikely of circumstances. It might be in Cairo; on a pilot training camp in South Africa, Florida or Canada; in Brussels or Paris in the heady days of liberation in 1944; or just maybe the RAF base at Habbaniya, Iraq. Nol Coward, Cecil Beaton, Freya Stark and my father all passed through the dusty hell of Habbaniya at some point or other. So far as Freyas route to Iraq was concerned, it could not have been more different from Jacks. Hitlers war picked them both up and deposited them there, she with some measure of choice; poor Jack with none at all. The tailor and the writer were polar opposites. No letter writer he, while her correspondence over a lifetime of exploration and books stretches to eight volumes. He: aspirant working class, locked into a trade that he could do in his sleep, brain dormant, left school at fourteen; she, fluent in at least seven languages, middle class and cosmopolitan, and acutely restless.

Next page