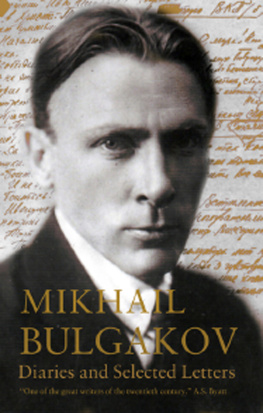

MIKHAIL AFANASIEVICH BULGAKOV was born in Kiev in 1891, the son of a professor of theology. Medicine, religion, and education were the dominant careers in his family. Politically, the family appears to have belonged to the liberal monarchist camp. Despite an early interest in literature and the theater, Bulgakov chose to become a doctor. In 1914, as a medical student, he volunteered with the Red Cross during World War I. After graduating from the University of Kiev in 1916, he served in the White Army during the Civil War, and was subsequently drafted by the Ukrainian Nationalist Army. These experiences during the chaos of the Civil War in Kiev and the Caucasus would have a profound effect on the writer and his work. His two younger brothers disappeared during the fighting around Kiev, and later surfaced in Europe. In 1919, while in the Caucasus, he made the decision to leave medicine for literature; soon after he almost emigrated, but was prevented from doing so by illness. By 1921 he was in Moscow where his literary career began in earnest. The Diaboliad collection, published in 1925, was his major publication of this time, since his masterpiece, Heart of a Dog, could not get past the censorship. This same period saw the partial publication of his novel about Kiev during the Civil War, White Guard. Publication ceased when the journal serializing the novel was shut down; however, enough had come out to arouse the interest of the Moscow Art Theater, which commissioned a play based on White Guard. This play, Days of the Turbins, was the source of Bulgakovs fame for the rest of his life, and was a major sensation both due to its vivid characterizations and its portrayal of a monarchist family in a sympathetic light rather than as monsters, which was the norm at this time. By the late twenties, when he had a number of other plays in production (Zoyas Apartment, Flight and The Crimson Island), Bulgakov had drawn down the wrath of the critics who felt that everything he wrote was essentially anti-Soviet. This was a period of extreme polarization, and Bulgakovs career was destroyed by 1929. He would have one more original play, Molire, staged in his lifetime (but it was quickly withdrawn from production due to the critics), but all publication of his prose ceased after 1927. In 1930 he wrote his famous letter to Stalin, defending his right to be a satirist, and asking that his country let him emigrate if it could not find any use for his talents. Stalin, who had actually seen Days of the Turbins many times, answered this letter with a phone call, and soon afterward Bulgakov had employment with a small theater. The Moscow Art Theater then found work for him, but most of the projects he worked on came to nothing, and the last eight years of his life were full of stress and disappointment. He broke with Stanislavsky and the Art Theater after the Molire debacle, and began to write Theatrical Novel as a way of venting his spleen. From 1928 on, Bulgakov had worked only sporadically on his major work, The Master and Margarita; in 1937 he dropped Theatrical Novel, which would remain unfinished, and concentrated on the novel about the devil in Moscow. When he died of sclerosis of the kidneys (which had killed his father at the same age) in 1940, he had finished The Master and Margarita, but had not completed final editing corrections. This novel, which would be considered one of the best Russian novels of the twentieth century, was not published until 1966-67 (and then in censored form), twenty-six years after Bulgakovs death. Heart of a Dog, however, was not published until 1987, the height of glasnost under Gorbachevmore than sixty years after it was writtena true indication of just how threatening satire could be to a totalitarian regime.

I would like to record my thanks to the British Academy for supporting me with a Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship, and with awards under the Academys Exchange Agreement with the Soviet Union, during the period when most of the research for this book was completed.

I would also like to thank Marietta Chudakova, Violetta Gudkova, Irina Yerykalova, Grigory Fayman and Viktor Losev, as well as the late Lyubov Yevgenyevna Belozerskaya-Bulgakova, for their help and encouragement. I am very grateful, too, to the staff of Pushkin House (the Literary Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences), the Saltykov-Shchedrin Library and the Cherkasov Theatre Institute in Leningrad, as well as to the staff of the Library of the Union of Theatrical Workers, the Moscow Arts Theatre Museum, the Central State Archive for Literature and Art, and the Manuscript Section and Reading Rooms of the Lenin Library in Moscow. I have collected and collated the material for this book from numerous archives, both State and private, and Bulgakovs second wife Lyubov Yevgenyevna was particularly generous in this respect. Bulgakov very often retained copies of the letters he himself had written, which means that some archives hold copies of documents published by another. This has enabled me to compare texts with publications, particularly those by Marietta Chudakova, Violetta Gudkova, Grigory Fayman, Yelena Zemskaya and Viktor Losev and, occasionally, to suggest variant readings. Viktor Losev and Viktor Petelin are the editors of the most comprehensive though far from complete collection of Bulgakovs correspondence, which was published in 1989. I am grateful to Viktor Losev for permission to work on Yelena Sergeyevna Bulgakovas diaries in the Lenin Library in 1990.

Special thanks are due to Lesley Milne; to all my colleagues in Cambridge; and, as ever, to my parents and family.

Without Ray, none of this would have been possible at all.

This edition first published in the United States in 2012 by Ardis Publishers, an imprint of Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

NEW YORK:

The Overlook Press

Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact

LONDON:

Gerald Duckworth Publishers Ltd.

90-93 Cowcross Street

London EC1M 6BF

www.ducknet.co.uk

Copyright 1991 by J. A. E. Curtis

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-139-7

This book is dedicated to Professor Tony Cross

and to my colleagues in the Department of Slavonic Studies,

as well as to the Warden and Fellows of Robinson College,

in gratitude for my happy years in Cambridge.

Mikhail Bulgakov is a Russian writer whose reputation has been growing steadily over the past decades, until he now stands amongst the giants Akhmatova, Tsvetayeva, Mandelstam, Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn and Brodsky of the Soviet period. Bulgakovs story, however, is a particularly unusual one, for he was scarcely published at all, either in the East or in the West, in his own lifetime, and his plays reached the stage only with great difficulty. He was indeed defeated by the stranglehold imposed on Soviet literature during the Stalin period and yet he would not give up. Time and time again we see him coming up with fresh inspiration and settling down to write new works, as soon as he has overcome the shock of yet another banning of a play or refusal to publish a work.