Russian Theatre Archive

A series of books edited by John Freedman (Moscow), Leon Gitelman (St Petersburg) and Anatoly Smeliansky (Moscow)

Volume 1 The Major Plays of Nikolai Erdman translated and edited by John Freedman

Volume 2 A Meeting About Laughter Sketches, Interludes and Theatrical Parodies by Nikolai Erdman with Vladimir Mass and Others translated and edited by John Freedman

Volume 3 Theatre in the Solovki Prison Camp Natalia Kuziakina

Volume 4 Sergei Radlov: The Shakespearian Fate of a Soviet Director David Zolotnitsky

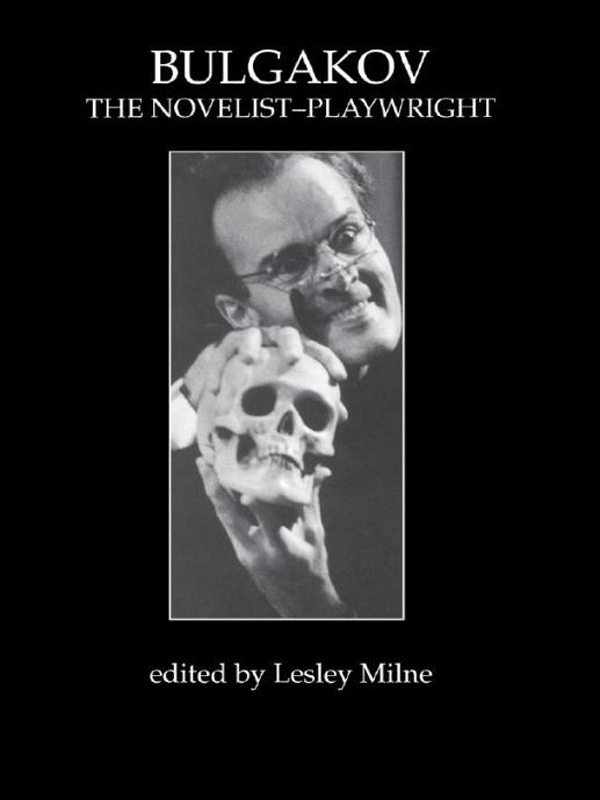

Volume 5 Bulgakov: The Novelist-Playwright edited by Lesley Milne

Volume 6 Aleksandr Vampilov: The Major Plays translated and edited by Alma Law

Volume 7The Death of Tarelkin and Other Plays: The Trilogy of Alexander Sukhovo-Kobylin translated and edited by Harold B.Segel

Volume 8 A Chekhov Quartet translated and adapted by Vera Gottlieb

Volume 9 Two Plays from the New Russia Bald/Brunet by Daniil Gink and Nijinsky by Alexei Burykin translated and edited by John Freedman

Volume 10 Russian Comedy of the Nikolaian Era translated and with an introduction by Laurence Senelick

Please see the back of this book for other titles in the Russian Theatre Archive series.

Copyright 1995 OPA (Overseas Publishers Association) N.V. Published by license under the Harwood Academic Publishers imprint, part of The Gordon and Breach Publishing Group.

All rights reserved.

First published 1995

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Amsteldijk 166

1st Floor

1079 LH Amsterdam

The Netherlands

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Bulgakov: Novelist-Playwright.-(Russian Theatre Archive, ISSN 1068-8161; Vol. 5)

I. Milne, Lesley II. Series

891.784209

ISBN 0-203-98741-1 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 3-7186-5620-5 (soft cover)

INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES

The Russian Theatre Archive makes available in English the best avantgarde plays, from the pre-Revolutionary period to the present day. It features monographs on major playwrights and theatre directors, introductions to previously unknown works, and studies of the main artistic groups and periods.

Plays are presented in performing edition translations, including (where appropriate) musical scores, and instructions for music and dance. Whenever possible the translated texts will be accompanied by videotapes of performances of plays in the original language.

ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

In 1991 the Russian-speaking world celebrated the centenary of the birth of Mikhail Bulgakov. There were academic conferences in Germany, Czechoslovakia, England, France, Hungary and, of course, Russia itself. In Kiev, Bulgakovs birthplace, there was a theatre festival at which his plays and adaptations of his novels were performed. There were commemorative articles in the press. The satirical journal Krokodil performed an extraordinary act of homage by devoting its entire May issue to Bulgakov, including a crossword in which all the across clues were from The Master and Margarita and all the down clues from The Heart of a Dog. This was interesting evidence of Bulgakovs cult status in the Soviet Union in 1991.

The glasnost of the latter half of the 1980s had promised so muchand had by 1990 delivered so much. The cultural and intellectual energy suppressed over the Brezhnev years of stagnation had exploded into the open. One of its manifestations had been the publication of hitherto banned literature. Another had been the freeing of publishing enterprises to respond to market forces. Both of these elements had contributed to the popularity of Bulgakov: works either banned, or never reprinted since the 1920s, or published in a small number of copies which changed hands at high prices on the black market, were now widely available to a mass readership. The dream articulated by the writer Vladimir Voinovich back in 1976 had come true:

Show me your publishing plans. [] Bulgakov? That Bulgakov? Mikhail Bulgakov? And youve planned for 30,000 copies? What? Theres no paper for any more? [] Who are thesePaderin, Pantielev? Have you ever seen anyone in a bookshop asking for a book by Pantielev? Publish Bulgakov in the number of copies that corresponds to the demand. How many? Lets say a million to start with. And why have you still not published Doctor Zhivago? What? Its written from an incorrect viewpoint? Listen, have you ever read a single interesting book that was written from a correct viewpoint? Put down a million for Doctor Zhivago too.

But in the second half of Bulgakovs centenary year, 1991, the Soviet Union disintegrated rapidly and so completely that by the end of the year it had formally ceased to exist. The Commonwealth of Independent States which replaced it was an unknown and untried structure. A period of economic and social trauma began: hyper-inflation; crises of production and distribution; power struggles and internecine wars in the republics of Central Asia and the Caucasus. With dreadful symmetry the whole vast Empire, built up over centuries, had been precipitated into a chaos reminiscent of the post- revolutionary period in which Mikhail Bulgakov began his literary career.

The value system that had sustained the Soviet Union had crumbled before there was anything to put in its place. In this vacuum, there was a dangerous tendency to seek answers as all-encompassing and unequivocal as those previously offered by the official ideology. This search naturally led to areas which had formerly been unofficial: religion; and literature that had stood aside from the ideologically imposed methods of socialist realism. This search for answers in literature is the context in which the post-Soviet Bulgakov cult in Russia has to be understood.

However, the only answer to be found in Bulgakov is the sanctity of human life and the primacy of the individual human conscience. If there is a philosophy to be gleaned from his works, it is to be found in the most unassuming of them all: A Country Doctors Notebook (Zapiski yunogo vracha). The young doctor of the title toils unglamorously in the wilderness; doing his job as well as he can; learning at the end that the only wisdom lies in awareness of his own ignorance and constant readiness to learn. It is in this spirit that the present volume is offered.

It is a snapshot of the international response to Bulgakov in the first half of the 1990s. The twenty-one contributors come from Britain, Canada, the Czech Republic, France, India, Russia, Ukraine and the USA. Among them are doyens of Russian literary studies and also young scholars at the beginning of their academic careers. This enthusiasm across the generations on an international front suggests that the Bulgakov cult represents not a transitory phase particular to Russia but a deep-seated and lasting cultural phenomenon.