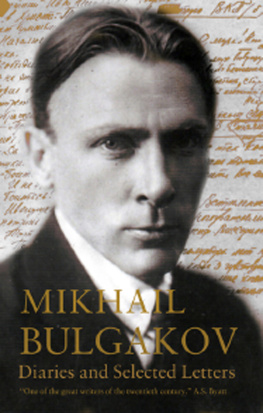

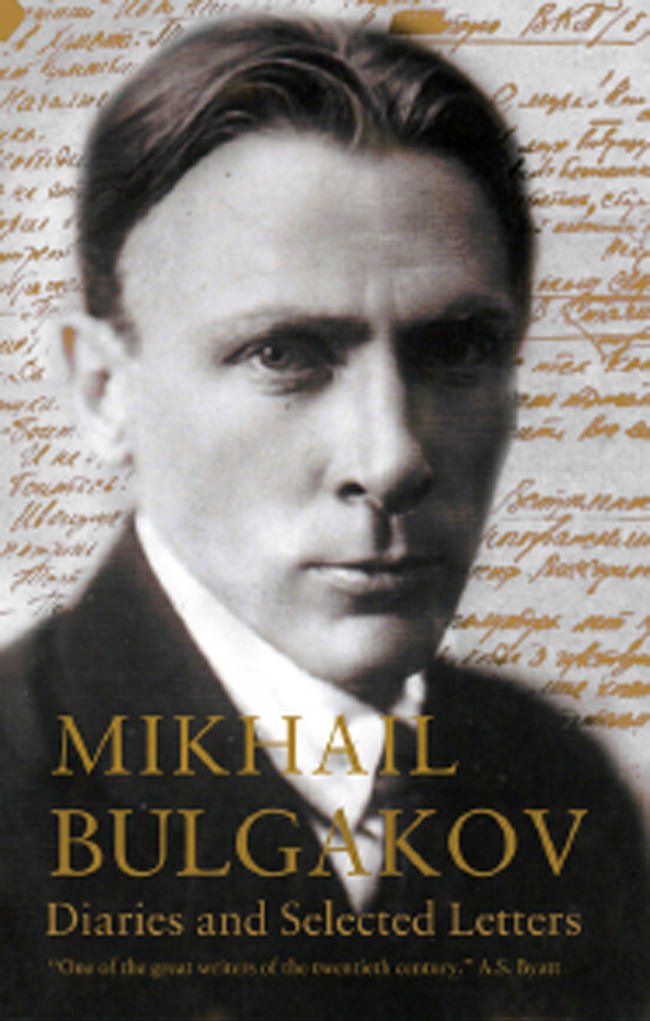

DIARIES AND

SELECTED LETTERS

Mikhail Bulgakov

Translated by Roger Cockrell

ALMA CLASSICS

ALMA CLASSICS

an imprint of

ALMA BOOKS LTD

London House

243253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almaclassics.com

This translation first published by Alma Classics in 2013

the Estate of Mikhail and Elena Bulgakov 2001

Translation and Introduction Roger Cockrell, 2013

Notes, Index and Extra Material Alma Classics, 2013

Pictures the Estate of Mikhail Bulgakov

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

ISBN: 978-1-84749-303-3

ePub ISBN 978-1-84749-338-5

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84749-338-5

All the pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge their copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Introduction

Am I thinkable in the USSR?

Mikhail Bulgakov, letter to the Soviet

government, 28th March 1930

This volume of Mikhail Bulgakovs diaries and letters covers a period of twenty years, from the time of Bulgakovs arrival in Moscow in the autumn of 1921 to his death in the same city in March 1940. In the early years, Bulgakov was overwhelmingly preoccupied with domestic concerns and day-to-day survival in an environment that was often less than welcoming. But his thoughts were also directed outwards and, as a journalist and avid reader of newspapers, he became a keen observer of the social and political scene. Many comments in the diary relate to the volatile international situation outside Soviet Russia, particularly the potentially explosive events in Germany and the growing hostility and conflict between Soviet-style socialism and fascism. As regards Great Britain, he was less than impressed by its imperialist ambitions and its population of slow-witted Brits (see diary entry of 20th21st December 1924).

By this time, however, Bulgakovs desire to become a writer and his growing awareness of his special talent had already taken shape within him. He knew that the future would be difficult: I bitterly regret, he wrote on 26th October 1923, that I gave up medicine, thereby condemning myself to an uncertain existence. But God will see I only did this because of my love of writing. Once the decision had been made, however, he entered the literary scene in the early to mid-1920s with an astonishing burst of creative energy, producing a major novel, The White Guard, several stories and a number of plays. Initially he met with some success: one story, The Fatal Eggs, was published, together with part of The White Guard, and a dramatic adaptation of the same novel, The Days of the Turbins, was staged in Moscow to great acclaim. But there it was to end, and a pattern was soon set that lasted for the rest of his life, in which he was attacked by a universally hostile and often virulent press, harassed by the secret police and subjected to crippling censorship.

After appealing to the government, he was given work as an assistant director at the Moscow Arts Theatre, but his urge to write remained undiminished. He found himself trapped, increasingly depressed, frustrated and overwhelmed by exhaustion and a sense of hopelessness. I am unable to write anything, he wrote to Maxim Gorky on 6th September 1929. Everything has been banned, I am ruined, persecuted and totally alone. He was to all intents and purposes imprisoned in the city that he had come to love. I have been injected with the psychology of a prisoner, he wrote on 30th May 1932. He felt sufficiently safe to reveal his innermost thoughts and fears to only a very few correspondents among them, his wife Yelena Sergeyevna, in a whole series of letters while she was away from Moscow in the summer of 1938, his brother Nikolai in Paris, the composer Boris Asafyev, the writer Yevgeny Zamyatin and his first biographer, Pavel Popov, with whom he was on especially friendly terms. With the renowned director and co-founder of the Moscow Arts Theatre, Konstantin Stanislavsky, the relationship was altogether more ambivalent, ranging from delighted admiration at Stanislavskys skill as a director during rehearsals (31st December 1931) to radical disagreement with the Arts Theatres impossible demands concerning the staging of his play Molire (22nd April 1935). As for the Moscow Arts Theatres other co-founder, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Bulgakov seems to have had little but contempt for him. Oh, yes, he writes with heavy sarcasm to his wife on 3rd June 1938, I am simply dying with impatience to show my novel to such a philistine. At times Bulgakov could be brutally abrupt. In his diary entry of the 23rd to 24th December 1924 he referred to the novelist Alexei Tolstoy as a dirty, dishonest clown, and elsewhere he accused the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold of being so lacking in principles that it was as if he walked about just in his underpants (letter of 14th June 1936).

We will never know how much Bulgakovs anger and sense of despair would have been mitigated had he been allowed to go abroad, but we are left in no doubt how vitally important such permission was for him. Although at one stage he asked to be deported (letter to Stalin of July 1929), he emphasized in many other letters that he wanted only to be able to travel abroad for a couple of months. For personal and medical reasons he wanted his wife to accompany him, but they were both prepared to leave Yelenas young son behind as a pledge of their return. At one stage, permission appeared to have been granted, only for hopes to be cruelly dashed. It was simply not to be, it seemed, and he was left with his yearning and his dreams. I dreamt about Rome, he wrote in a letter of 11th July 1934, a balcony, just as described in Gogol, pine trees, roses a manuscript. The Rome of Gogol, the Paris of Molire (which occupied a place in his heart that was second only to his beloved native city of Kiev), sunshine and the Mediterranean all lured and beckoned, all so close and yet so unattainable, except through his imagination. And by the mid-1930s imagination seemed to be all that remained to him. He continued to work on his novel, but he had given up all hope of it ever seeing the light of day. The most that he could hope for, as he wrote to Yelena on 15th June 1938, was that the novel would be of sufficient worth for it to be put away into a dark drawer.

Bulgakov lived a tragically short life, not even seeing his fiftieth birthday, but it is something of a miracle that he was allowed to continue as long as he did, at a time when other similarly inclined fellow writers were disappearing into the maw of the gulag. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bulgakov had not shared in any initial rush of enthusiasm for the 1917 revolution. Boris Pasternak, for example, speaking through his hero Yury Zhivago, saw the revolution as magnificent surgery, whereas for Bulgakov it was the harbinger of a tragedy that would lead Russia to the abyss. Furthermore, Bulgakov remained openly unrepentant about his political sympathies. In his letter to the secret police (OGPU) of 22nd September 1926 he stated that during the civil war he had been entirely on the side of the Whites, whose retreat filled me with horror and incomprehension. How then did he escape imprisonment, or even worse? Was it perhaps through the intercession of Stalin? Certainly, Stalin particularly admired