It almost goes without saying that a book of this nature requires the help and advice of numerous people and establishments. Those who were of particular help are listed here; others who helped on particular aspects of the book are mentioned in the notes that they helped compile.

I must particularly thank Miss Heather Ann Bingham, the last known direct descendant of the Bingham family, who resides in British Columbia, for graciously agreeing to my request to study and publish George Binghams papers.

The generous help of John Montgomery, Librarian at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies for identifying the whereabouts of Binghams Peninsular letters which, it turned out, had been transferred to the Army Museum, is much appreciated.

I am eternally grateful to Dr Peter B. Boyden, Assistant Director (Collections) at the Army Museum, Chelsea, for agreeing to supply copies of Binghams Peninsular diaries; Mrs Lesley Hamilton, Assistant Secretary to the De Lancey & De La Hanty Foundation Ltd. (the present proud owners of the original HMS Northumberland diary), for granting permission to obtain a copy of the diary from the photocopy of the original held by the British Library and Matthew Jones, Archivist at the Dorset Record Office for copies of the St Helena letters.

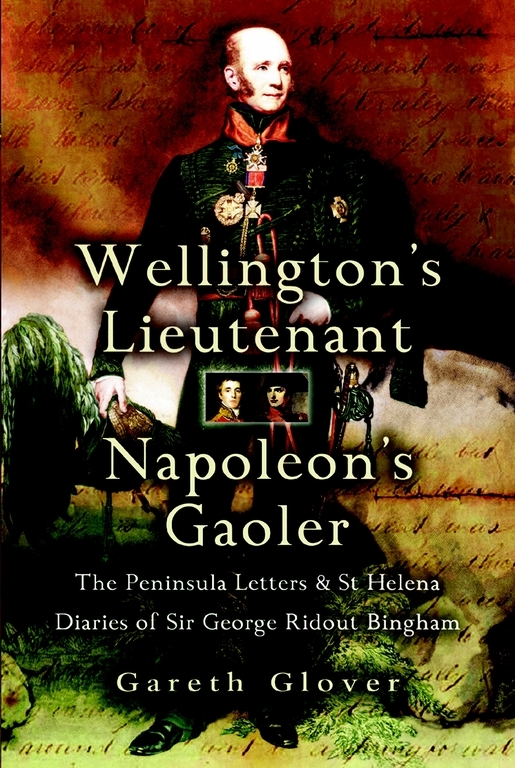

With regard to the various illustrations, I must thank the British Library for their kind permission to reproduce the only known painting of George Bingham (Reference Eg3715 f19). For the views of St Helena by Bellasis, I must thank Barry Weaver of the St Helena Virtual Library and Archive. The 53rd at Talavera is reproduced by kind permission of Lieutenant Colonel P. J. Wykham and Major W. J. Spiers, RHQ, The Light Infantry. The views of Spain reproduced from Major Andrew Leith Hays A Narrative of the Peninsular War, 1830 edition is from my own collection.

I must also thank Brigadier Henry Wilson, Publishing Manager for Pen & Sword Books for his support, encouragement and enthusiasm for the project, from the moment I first brought the idea to his attention.

Lastly, but certainly not least, I acknowledge the unwavering support of my incredibly understanding and patient wife Mary and dear children Sarah and Michael.

Bibliography

Anon, The Royal Military Calendar , T. Egerton, London, 1820

Chandler, D.G., Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars , Arms & Armour, London, 1979

Clinton, H.R., The War in the Peninsula , Warne, London, undated

Clowes, W.L., The Royal Navy a History , Chatham, London, 1899

Cockburn, Sir G., Buonapartes Voyage to St Helena , Lilly, Boston, 1833

Esposito, Brigadier V.J. & Elting, Colonel R.E., Military History & Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars , Arms & Armour, London, 1980

Forsyth, W., History of the Captivity of Napoleon at St Helena , Murray, London, 1853

Gregory, D., Napoleons Jailer , AUP, 1996

Gurwood, Lieutenant Colonel, Duke of Wellington Dispatches , Murray, London 1834

Hart, Lieutenant A. G., Annual Army List 1840 , Murray, London 1840

Haythornthwaite, P.J., The Napoleonic Source Book , Guild Publishing, London, 1990

Wellingtons Military Machine , Guild Publishing, London, 1989

Jones, Sir J.T., Journal of Sieges in Spain , Weale, London, 1866

Kauffmann, J.P., The Black Room at Longwood, Four Walls Eight Windows, New York, 1999

Kemble, J., Napoleon Immortal , Murray, London, 1959

St Helena, Gorrequers Diary , Heinemann, London, undated

Latimer, E.W., Talks of Napoleon at St Helena , Mc Clurg, Chicago, 1903

Martineau, G., Napoleon Surrenders , Readers Union, Newton Abbot, 1973

Napoleons St Helena , Murray, London, 1968

Mullen, A.L.T., The Military General Service Roll 17931814 , London Stamp Exchange, London, 1990

Myatt, F., British Sieges of the Peninsular War , Guild Publishing, London, 1987

Napier, W.F.P., History of the War in the Peninsula , Boone, London, 1835

Oman, Sir C., A History of the Peninsular War , Oxford, 1902

Wellingtons Army 180914 , Arnold, London, 1913

OMeara, B.E., Napoleon in Exile , Simpkin, London, 1822

Rosebery, Lord, Napoleon the Last Phase , Humphreys, London, 1906

Warden, W., Letters from St Helena , Ackermann, London, undated

Chapter One

The Peninsular letters

Although Britain and France had been almost continually at war since 1793, except during the short lived Peace of Amiens of 1802, it had in many ways been a limited war. Britain, through its navy, had gained complete supremacy of the seas; whilst Napoleon and his ever growing French Empire dominated the European land mass. For most of this period, therefore, neither was in a position to seriously challenge the others control of their given element. France had cowed all of the major powers in Europe, frustrating Britains attempts to bring her Empire to its knees through grand alliances with the other traditional power houses of Austria, Prussia or Russia. Britain had used her navy to capture virtually all of the French, Dutch and Danish outposts throughout the world. This had a hugely beneficial effect on the economy of Britain but was extremely detrimental to the British forces, which had to be thinly spread across these pestilential islands and suffered frighteningly high mortality rates. The few attempts to land a substantial British army on the continent of Europe generally led to abject failure or, where victory was gained over the local French forces such as at the Battle of Maida in Southern Italy, the inability to maintain sufficient numbers to stand against the French forces summoned to counter the threat, caused a rapid re-embarkation. Such pyrrhic victories gave some cheer to the besieged British populace, but proved a merely temporary irritant to Napoleons driving ambition and Britain could only look upon the minor peripheral states of Sweden and Portugal as her allies.

This all suddenly changed in 18078, when Napoleon made the fatal decision not merely to eradicate Portugal but also to enforce his own brand of democracy on his erstwhile ally, Spain, the final bastion of the venal and arrogant Bourbon dynasty. His usurping of the Spanish throne for his brother Joseph was the catalyst for a general insurrection throughout the country. Spanish representatives were soon in London demanding support in the form of money and arms, which they did receive in copious amounts; but were reluctant about troops, as the enthusiastic insurgents were convinced that they were capable of defeating the French hordes alone; a belief that was unfortunately strengthened by the fortuitous defeat of a French corps at Bailen.

Ten thousand troops under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, later to become famous as the Duke of Wellington, was formed into an expedition to aid Portugal oust the French invaders. This army landed at Mondego Bay in August 1808 and, following victories at Rolica and Vimiero, General Jean Andoche Junot agreed to sign the Convention of Cintra by which the French forces would leave Portugal on British ships! The convention was heavily criticized in Britain and Generals Sir Hew Dalrymple and Sir Harry Burrard with Wellesley, who had been supplanted by these senior officers as the British Army in Portugal significantly increased in numbers, were called home to face an enquiry. Only Wellesley was exonerated although the agreement had achieved the complete removal of French troops from Portugal including two significant fortresses, without further loss.