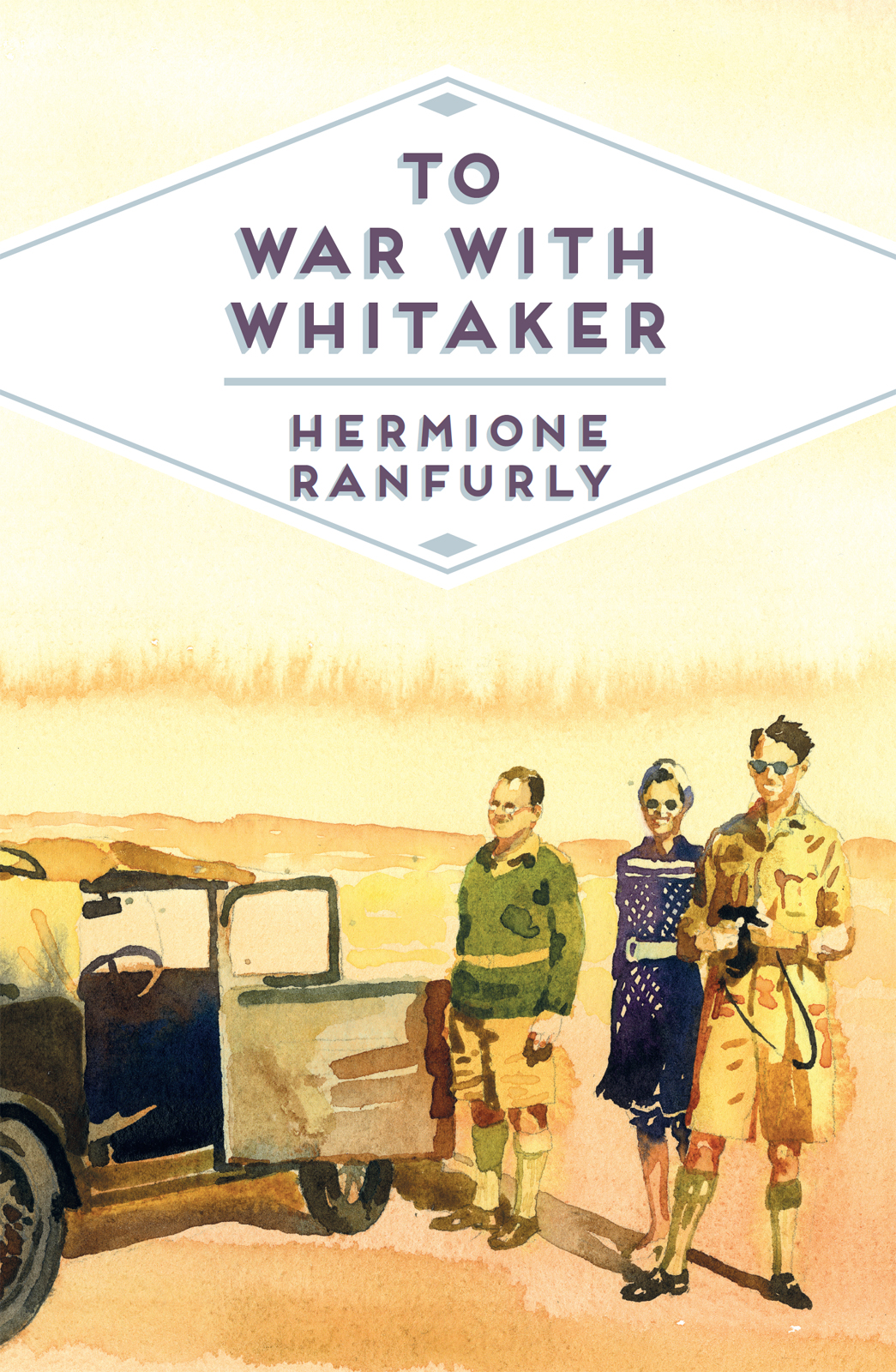

Hermione Ranfurly

TO WAR WITH

WHITAKER

PAN BOOKS

Contents

Preface

Since I was about five years old I have kept a diary. Though I am now eighty, most of these have survived my many adventures and travels and sometimes I glance at them to remember with laughter.

Growing up is like entering a jungle where some of the larger creatures look alarming and possible man-eaters; and most of the smaller ones like insects go unnoticed. As one grows up the jungle gets denser and so, most likely, do you.

But now I am old and in the Departure Lounge though certainly still growing up I look back with amusement at how cock-sure I became and how often wrong; so many of those creatures who, at first, looked big and fierce became my life-long friends; so many insects turned out to be brilliant, fascinating and kind companions.

My diaries, written mostly at night and always in haste, in nurseries, school rooms, cars, boats, aeroplanes and sometimes in loos, expose how we all arrive, helpless, innocent and ignorant; and then, as we step gingerly into the jungle, show how afraid, selfish, show-off and silly we often are. Mine also prove how lucky I have always been. Most of the creatures in my jungle have been extra special.

Two friends who helped me through thick and thin I never met: Alexander the Great, who said, One must live every day as if it were ones last, and as if one would live forever, both at the same time, and Oscar Wilde, who said, All of us are standing in the gutter but a few of us are looking at the stars. These two remarks should get anyone through their jungle.

Then, of course, there was Dan; forever the best human being Ill ever know.

I have only one regret: that soon the diaries must stop and no longer record with laughter what happened next. This is an account of my life during the six years of World War II.

1. The Storm Breaks

Dan Ranfurly and I were married in London on 17 January 1939. We were both twenty-five years old. We had met in Australia in 1937 when he was Aide-de-Camp to Lord Gowrie, the Governor-General, and I was personal Assistant to Lord and Lady Wakehurst, Governor of New South Wales.

When our different terms were up and we met again in Europe we heard much talk of war Hitler was on the prowl. We knew that England had given a guarantee to Poland but, like most other people, we could not believe that Hitler would risk war with Britain and France. In late August 1939, when the German-Soviet agreement was broadcast to the world, people in the know looked grim but we, and our generation, took little heed. In that lovely hot summer Dan and I left our small flat in London and drove up to the highlands of Scotland for a holiday. The countryside looked more beautiful than ever. We were supremely happy and carefree when we arrived to stay with Joe and Ann Laycock beside Loch Torridon in Ross-shire to fish and stalk deer.

31 August 1939 Upper Loch Torridon, Scotland

Dan, Andrew the Ghillie and I set off early this morning. We took the mountain track through the wood. Cobwebs glittered on the grass and brambles, rabbits thumped their warnings and hustled away into the bushes.

Soon we began wading up steep heathered hills, catching our toes in roots and tufts, leaving deep marks in the peat hags. Andrew went easily ahead his rifle slung on his shoulder, his lunch bulging his pocket. Several times I slumped to the ground and looked back at the blue loch water below. I wondered if I was tired after the long drive from London yesterday or am just lazy. How does one know the difference? I counted three out loud to make myself get up and each time Andrew looked back and grinned.

Presently we reached bare rock and began to climb. It took ages to reach the top. There we lay in the sun and spied for stags through a telescope while we ate our lunch, each with a halo of midges. Deer were grazing in a corrie far beyond and below us, and through the long hot afternoon we made a great detour and stalked them, finally crawling along a burn over shining brown pebbles till we were in range. Dan fired and missed. I was glad the stag looked so beautiful.

Long after the sun went down we were still walking home. We discussed whether toenails came off after slithering down steep slopes in sodden shoes. They laughed at me for wearing tennis shoes, which I always use for mountains. We talked about our wedding in January and this, our second honeymoon. Andrew told us all about his job and his family.

When we came out of the wood and crossed the lawn it was dusk. Lights were on in the house. We opened the front door and were surprised to see suitcases in the hall. General Joe Laycock came out of his study and for a moment I thought he was going to be cross because we were nearly late for dinner. He looked tired, or older than he did at breakfast. Dear Dan and Hermione, welcome back, he said. We are not changing for dinner. He hesitated, and then said very slowly as if it hurt him I want you to give me a lift in your car at day-break tomorrow. I must go south and so must you. Bob has telephoned from the War Office: the Germans are marching on Poland.

No one spoke or ate much at dinner and immediately afterwards we went upstairs to pack and go to bed. Soon it will be dawn. Dan is fast asleep. I have counted sheep in vain they all turned into Germans.

3 September 1939 Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire

Two days ago we left Torridon. It seems an age. As we stacked our guns, golf-clubs and fishing rods into the back of our Buick, fear pinched my heart: those are the toys of yesterday I thought; they belong to another world. General Laycock, Dan and I sat in front. We hardly spoke. No doubt the General was thinking of his sons, Bob, Peter and Michael, who will all have to go to the war. Questions teemed through my mind: where will Dans Yeomanry, the Notts Sherwood Rangers, go? Will I be able to see him? Mummy, ill in hospital in Switzerland should I fetch her back to England? And Whitaker our cook-butler perhaps he is too old to be a soldier? It was raining. The windscreen wipers ticked to and fro and it seemed as if each swipe brought a new and more horrifying thought to me. We had started on a journey but to where? And for how long?

We sent a telegram from Inverness to our flat in London and drove on to Edinburgh where we were surprised to find the street lamps out. All night we drove slowly, through thick fog. It was hard to see without headlights. None of us slept.

We dropped the General at his house, Wiseton, near Doncaster, where we ate a hurried breakfast and then drove on to London. Whitaker and Mrs Sparrow, our charlady, were waiting for us, and a telegram from Dans Yeomanry saying he must report immediately at Retford in Nottinghamshire. After reading this Dan asked Whitaker if he would like to go with him. The old fatty looked over the top of his spectacles and said, To the War, my Lord? Very good, my Lord. Then we started to pack.

Short and stout, his huge face much creased from smiling, Whitaker has many abilities all self-taught but I just cant imagine him going

This morning we piled camp beds, saddle and saddle bags into the back of the Buick and started: Dan in uniform, Whitaker in his best navy pinstripe suit and myself in a fuss. We listened to Mr Chamberlain broadcasting that a state of war exists as we sped up the Great North Road.

Dan left me here with Hilda, his Mother. She offered him her beautiful chestnut mare to be his second charger and he accepted gratefully. In twenty minutes, he and Whitaker were gone...

Thousands of children are being evacuated from London to the country. They, and their parents, must feel as desolate as me.