by Karin Nyman

I was five at the outbreak of the Second World War. For us children in Sweden it soon started to feel like a normal state of affairs, almost a natural state, for all those around us to be at war. We took it for granted that our country had somehow secured guarantees not to be involved, and it was constantly being stressed to us: No, no, dont be scared, the war wont be coming to Sweden. It felt special, but in some strange way reasonable and justified, for us to be the ones who were spared.

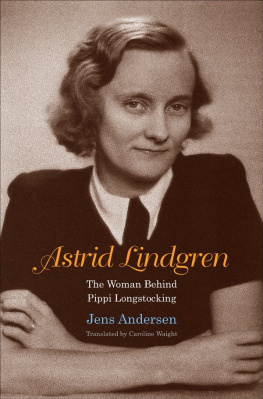

It did not seem strange to me that my mother cut articles out of the papers and pasted them into exercise books; I assumed it was just something parents did. Now I know that she was very probably unique, a 32-year-old housewife with secretarial training but no experience of thinking in political terms, who was so determined to document what was happening in Europe and the world to her own satisfaction that she persisted with her cuttings and commentaries for all six years of the war. It is also extremely rare and special to find diary entries so well written that they can be reproduced unabridged and instantly make gripping reading.

That is why Salikon Frlag originally wanted to publish them, of course, because they give such a good picture of ordinary family life in Sweden in the war years and so vividly express the despair of the powerless at the horrors they read about in the papers every morning. Daily papers were the primary news source, there was no television, and although there was radio it had no live broadcasting or correspondents the radio news consisted of readings of the telegrams received f rom the Swedish news agency Tidningarnas Telegrambyr (TT).

After the first year of the war, however, Astrid gained access to a fresh source of information. She was offered state security work at the secret Postal Control Division, as a censor of military and private post sent to, and coming from, other counties. The letters had to be steamed open and read, the aim being to find and black out any locations of military importance or other classified information. It was all so hush-hush that we children never knew what her late-evening job was. But the restrictions did not prevent her from copying out, or quoting sections of, the more interesting letters in her diary, for the insight they gave into conditions in the occupied countries.

The diaries show another side of Astrid Lindgrens authorship. She was admittedly still not a published author, nor had she any intention of becoming one. But in the midst of the convulsive tensions of the time, at some point in the winter of 1941, she started coming out with her unbridled stories of wild, freedom-loving Pippi Longstocking first as a bedtime story for me, then at any time of day, for a growing audience of children, her own and others, all wanting to hear more. In early 1944, she wrote down some of the stories and made them into a book. It was published by Rabn & Sjgrens Frlag in 1945, having first being refused by Bonniers. That was how it all began. It rather takes your breath away to think that before that relatively recent date, Pippi Longstocking simply did not exist and Astrid Lindgren could not have had the faintest idea of the career as a childrens writer which lay ahead of her.

And that she, and we, did not know was probably just as well! How utterly unreal a glimpse of her future global fame would have seemed to her then. I can imagine that she might have looked away in terror at the sight of it. In old age, with her renown a fait accompli and her eyesight too poor for her to read the piles of readers thank-you letters and their touching testaments to the crucial role some of her books had played in their lives, when I had to read the letters out loud to her, she would sometimes look up, interrupt me and say, sounding almost fearful: But this is remarkable, dont you think? Well yes, I would say, because I did. Truly remarkable.

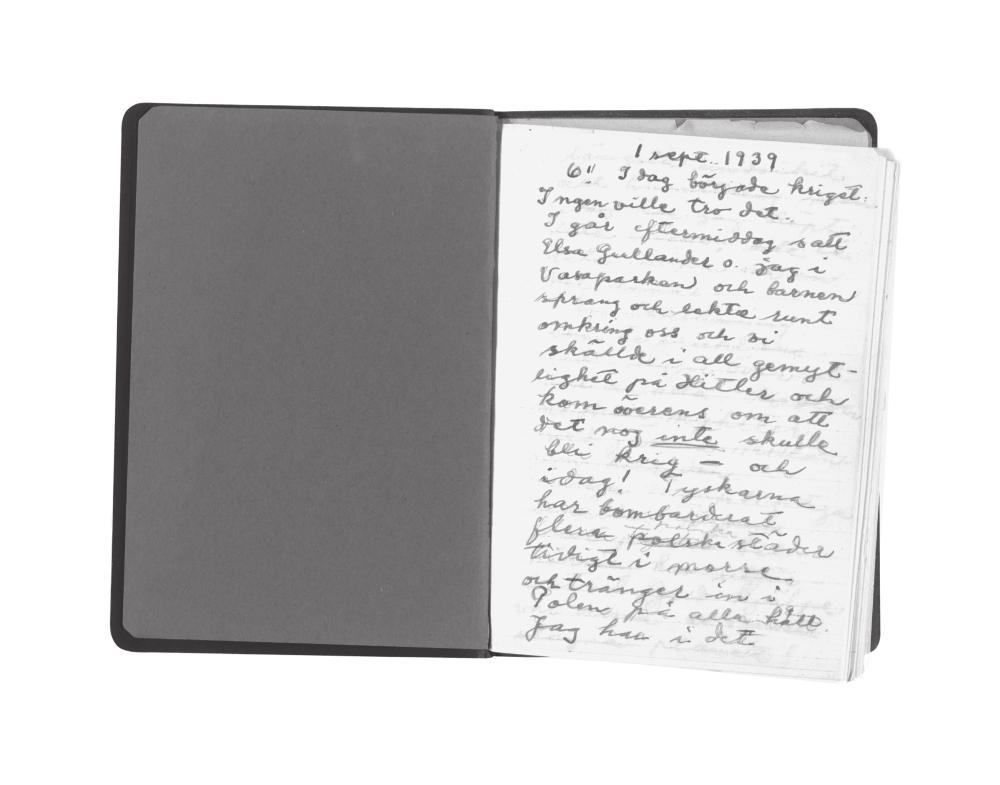

Until 2013, seventeen leather-bound diaries lived in a wicker laundry basket at Astrid Lindgrens familiar home address, 46 Dalagatan in Stockholm. The diaries cover the years 193945. Her own name for them was The War Diaries and they are now accessible to the public for the first time. The diaries bulged with press cuttings, pasted in between Lindgrens handwritten entries. She refers now and then to the time it has taken her to save newspapers and magazines, sift through them and select items to cut out for pasting into her note-books, but it was a task she set herself and she carried it through to the end, the number of cuttings increasing with every passing wartime year. In her preface to the Swedish edition, Kerstin Ekman, another eminent Swedish writer, expresses her admiration for Lindgrens unusual resolve:

War diaries were kept by general staffs and units out in the field. Their operational maps, battle accounts and observations would form the foundation of future history writing. It is striking to think of this 32-year-old mother of two and office-worker taking on the same sort of task with such seriousness. But only for herself, to try to understand what was going on.

The Swedish edition includes facsimiles of quite a number of the two-page diary spreads featuring pasted-in newspaper cuttings. Here and there in this edition the reader will come across references to such accompanying cuttings and Pushkin Press has asked me to provide an explanatory note wherever one is necessary.

Astrid Lindgrens own comments are in round brackets, whereas square brackets indicate clarifications added by the Swedish editors, with a few additions for this English-language edition, to provide a little more background information for a non-Swedish readership.

The ambition was to retain the overall character of the original, but dates and abbreviations have been harmonized. Biographical names have been corrected and some place names have been put into English. Where the original work was in English, or in long lists of Swedish works, book and film titles have also been rendered in English.

Then as now, Swedes often use England as shorthand for any part of the British Isles, and that is Lindgrens practice throughout her diaries. It seemed less jarring to render this as Britain in the English-language edition.

SARAH DEATH

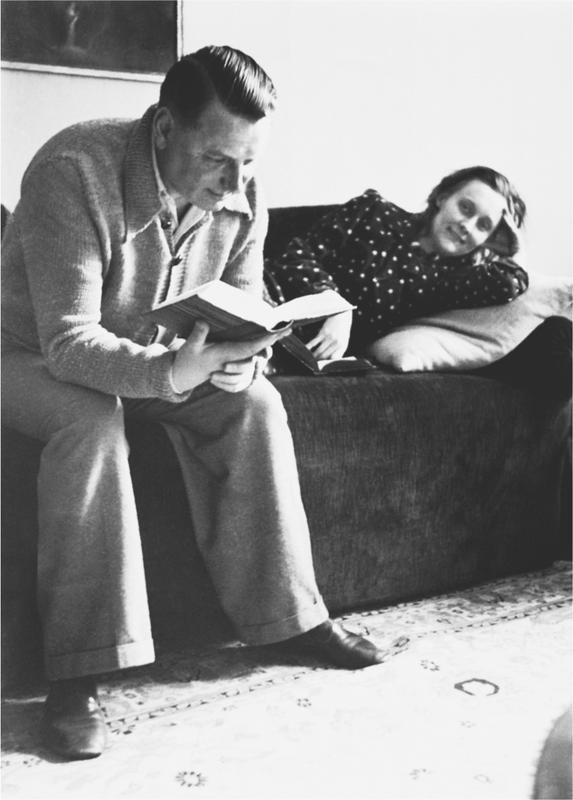

Astrid and her husband Sture at home in Vulcanusgatan, 1939.

1 SEPTEMBER 1939

Oh! War broke out today. Nobody could believe it.

Yesterday afternoon, Elsa Gullander and I were in Vasa Park with the children running and playing around us and we sat there giving Hitler a nice, cosy telling-off and agreed that there definitely was not going to be a war and now today! The Germans bombarded several Polish cities early this morning and are forging their way into Poland from all directions. Ive managed to restrain myself from any hoarding until now, but today I laid in a little cocoa, a little tea, a small amount of soap and a few other things.

A terrible despondency weighs on everything and everyone. The radio churns out news reports all day long. Lots of our men are being called up. Theres a ban on private motoring, too. God help our poor planet in the grip of this madness!

2 SEPTEMBER

A sad, sad day! I read the war announcements and felt sure Sture would be called up but he turned out not to be, in the end. Countless others have got to leave home and report for duty, though. Were in a state of intensified war readiness. The amount of stockpiling is unbelievable, according to the papers. People are mainly buying coffee, toilet soap, household cleaning soap and spices. Theres apparently enough sugar in the country to last us 15 months, but if nobody can resist stocking up well have a shortage anyway. At the grocers there wasnt a single kilo of sugar to be had (but theyre expecting more in, of course).