Contents

Guide

Introduction by Erik Larson

Mary Churchills War

The Wartime Diaries of Churchills Youngest Daughter

Edited by Emma Soames

Foreword ERIK LARSON

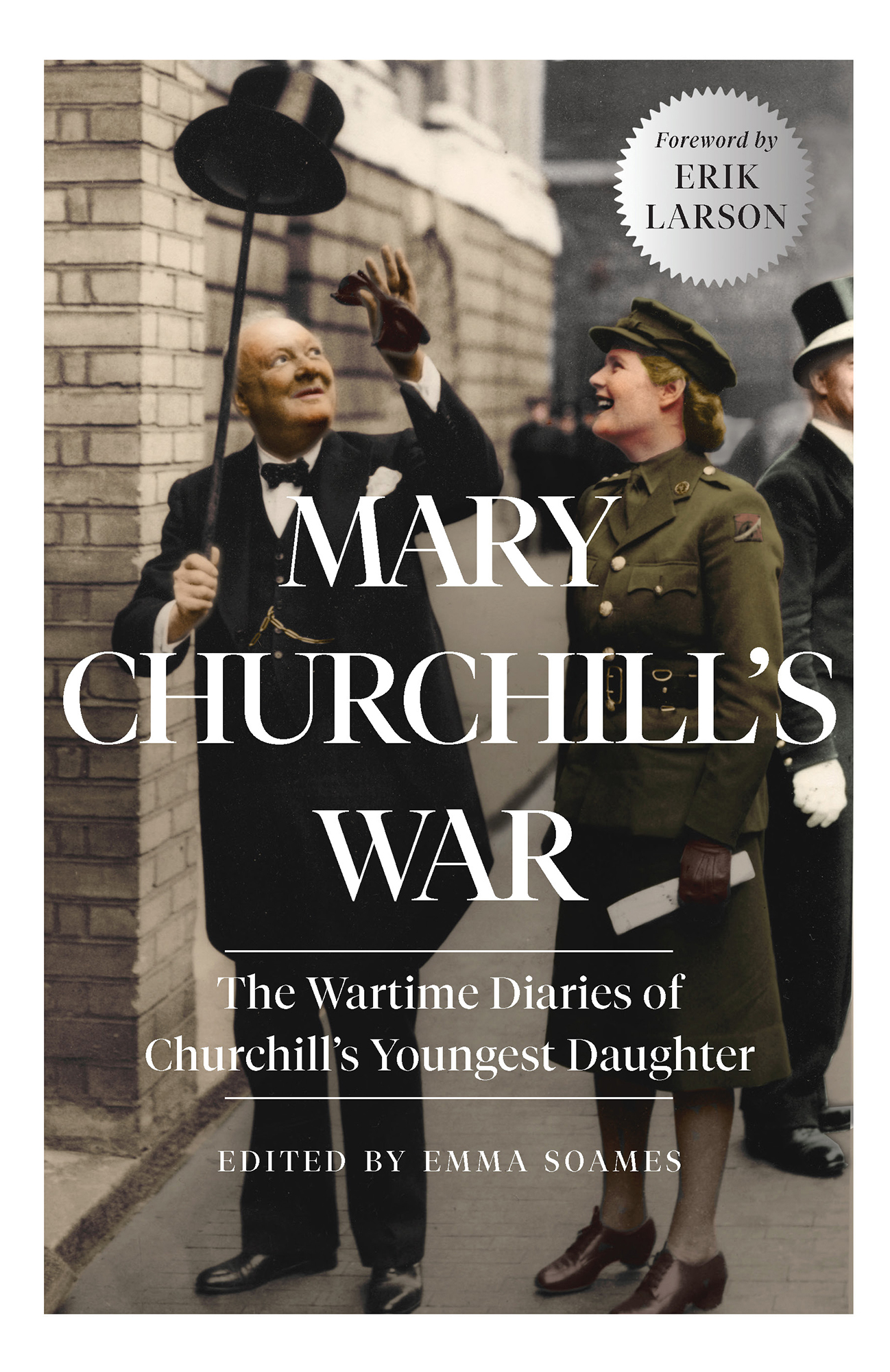

When I first learned of the existence of Mary Churchills diary, I knew that I absolutely had to read it. I was researching a book about how Winston Churchill, his family, and his close advisors endured the German air campaign of 1940-41, which included the period we know today as the Blitz, when the Luftwaffe bombed London 57 nights in a row. There are many books on the war and on Churchill, of course, but I wanted to tell a different kind of story, one that captured an intimate sense of how the family really managed to get through that periodhow they dined, what they did for fun, and so forth. Mary was 17 when her father first became Prime Minister, on May 10, 1940, the day Hitler invaded the Low Countries and turned the so-called Phoney War into an all-too-real conflagration. I could not imagine a more compelling perspective than that of Churchills daughter in that time of turmoil.

When I began my research, Marys diary resided in the vast collections of the Churchill Archives Centre at Churchill College in Cambridge. I had read bits of it that Mary herself had excerpted in a memoir, A Daughters Tale, published in 2011, three years before her death. When I inquired about reading the complete collection, I learned that its guardian, Marys daughter Emma Soames, had not yet made it available to researchers. This was deeply disappointing, but as a writer of history, I was accustomed to rejection and frustration. The archives director, Allen Packwood, suggested that I try contacting Ms. Soames directly. Having been raised on the motto nothing ventured, nothing gained, I composed a request, which Mr. Packwood then relayed to her. Weeks passed, and I assumed my petition had failed. I plunged into other diaries by other men and women of the era, but always with a flicker of hope that Id get a chance to read Marys.

One morningto be precise, at 4:57 A.M. on the last day of February, 2018I received an email from Ms. Soames, granting me permission, and soon afterward I found myself in the quiet embrace of the Archives Centre, slipping backward in time to Marys world. I found myself engaged, charmed, and enthralled. She made entries on all manner of subjects, in clear and articulate prose, and, thankfully, in easily legible handwriting. For the record, I did not encounter a single misspelling or grammatical breach. To read Marys diary is to look over her shoulder into her world, and see what she saw, and hear what she heard, as she moved though her days, gracefully coping with the destruction and chaos of those fraught times.

She embodied everything I hoped to convey about the Churchills capacity for endurance, and for love. Because really thats what suffuses this diary: Lovefor her father, her mother, and above all for life. One always has to ask, of course, what biases a diarist brings to her vision, but in Marys diary there is a lovely guilelessness that makes it all the more valuable. I knew immediately that these pages would provide an element often missing in the realm of Churchill scholarship, which skews toward massive great man biographies in which, necessarily, there is simply not room or time enough to consider the views of a seventeen-year-old girl. Through Marys eyes we see Churchill not merely as a political titan, but also as an indulgent, if at times aloof, parent who, despite the deepening war, is attentive to such small details as a daughters 18th birthday and the christening of a grandson. Mary gives us an intimate portrait of her father, her mother Clementine, and her own rich life as their country mouse, sequestered for a time in the countryside to keep her safe. This country mouse, however, soon rises to command a force of female anti-aircraft gunners.

I confess to have fallen for Miss Churchill. She is charming, funny, spirited, and deeply empathic. She loved her father very much, and grieved when he came under attack by the press and political foes. But she also loved to have fun. Her diary is full of moments that attest to the idea that even in the midst of war, life has its bright side. We see Mary attending dances at nearby RAF bases, and once being forced to flee with her hosts into a muddy air-raid trench as bombs fell into a nearby field. The bombs did no damage; the mud, however, destroyed a favorite pair of suede shoes. We go with Mary to Queen Charlottes Annual Birthday Dinner Dance, Londons debutante ball, held in March 1941 in the bomb-proof cellar of a hotel, where the festivities continued even as an air-raid began and anti-aircraft guns from a nearby emplacement began firing away. Here Mary examines the years fresh crop of debutantes with a cool eye. I must say, she writes, we all agreed this years debs arent much to write home about.

After the ball, and the raid, she and her friends moved on to dance at a favorite nightclub, the Caf de Paris, only to find that the club had just been destroyed by a German bomb that exploded on the dance floor, with great loss of life, including the decapitation of its famed bandleader, Kenrick Snakehips Johnson. Mary was struck by the awful juxtaposition of joy and death. They were dancing & laughing just like us, she writes. They are gone now in a moment from all we know to the vast, infinite unknown.

In these pages the war is always near at hand, but what I love most are the little moments, the grace notes, that shed light on daily life. One of my favorites is when Mary, on a fine summers day in the country, decides to go for a swim. It was so lovely, she tells us: joie de vivre overcame vanity.

Casting aside all convention, she jumped in without a bathing cap.

I am grateful to have had the chance to spend time with Mary. It is fair to say that my own book about the Churchills would have been a much colder affair without the joyous clarity of this particular teenage girl, enthralled with life and her own youth.

Introduction

I am not a great or important personage, but it will be the diary of an ordinary persons life in war time though I may never live to read it again, yet perhaps it may not prove altogether uninteresting as a record of my life or rather the life of a girl in her youth, upon whom life has shone very brightly, who has had every opportunity of education, interest, travel and pleasure and excitement, and who at the beginning of this war found herself on the threshold of womanhood.

With Churchillian prescience for great events, and blessed with the family gene for recording them, Mary Churchill began keeping a diary in earnest in January 1939, recording the thoughts of a rather prim sixteen-year-old obsessed with her pony, the state of her fingernails and with her shortcomings in the sight of the Lord. Eight months later, just before her seventeenth birthday, war was declared and a few days later, on 18 September, she muses on her future one that turns out to more than fulfil her own, or anyone elses, expectations.

By 1939, the three elder Churchill siblings had all left home, but Mary was living with her parents, moving first from Chartwell to Admiralty House and thence in short order to No. 10 Downing Street. Thanks to her assiduous journalling it is not long before the reader of these diaries is eavesdropping on history and her descriptions of great events as viewed from her fathers elbow.