Contents

Guide

Page List

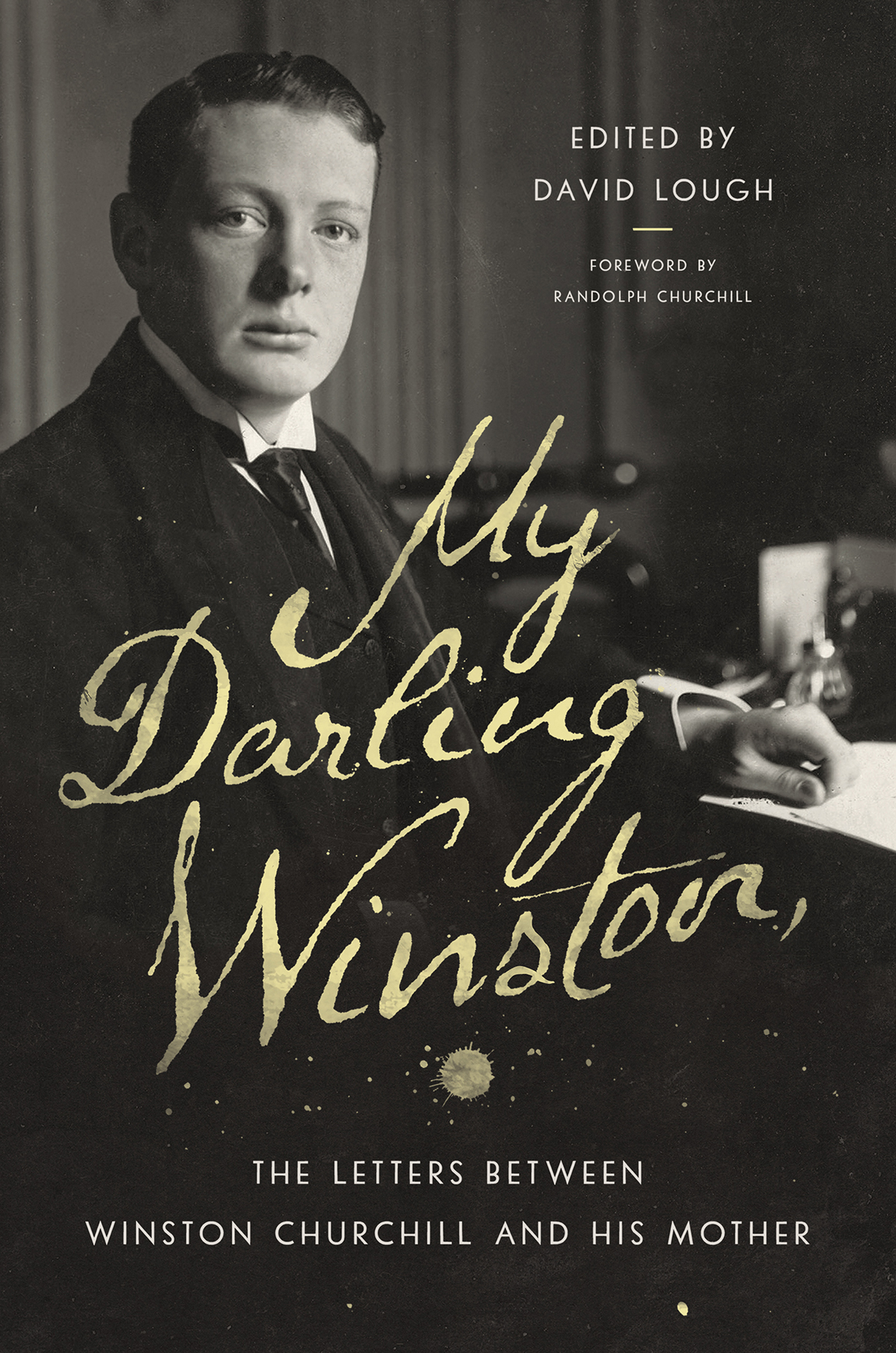

My Darling Winston

THE LETTERS BETWEEN WINSTON CURCHILL AND HIS MOTHER

DAVID LOUGH

To Felicity, a brilliant mother to our five children

CONTENTS

by Randolph Churchill

I VERY MUCH welcome the first publication of these letters between my great-grandfather, Sir Winston Churchill, and his mother, Jennie, as a correspondence in their own right. I believe that history has under-appreciated the role of Jennie Jerome (as she was known at her birth in America) in shaping the early years of her son, Winston, and the influence she had on the life of a great statesman. Nothing illustrates better how she did it than these letters.

Jennie Jerome and her American ancestors, who were of early pioneering stock, are legends in my family history. My great-grandfather loved the stories of supposed Iroquois antecedents, which we are now told are untrue. But Jennies father, the fabulous Leonard Jerome, created a spark of energy in her, because Jennie was beautiful, talented and captivating. So much so that when, aged nineteen, she met the young Lord Randolph Churchill when they were guests on board HMS Ariadne in 1873, he proposed to her just two days later. Although Jennies parents did not think that the second son of a duke was good enough for their daughter, the young couple were very much in love. They married in 1874 and Winston was born later that year.

Jennie had to bring Winston up almost single-handed once he was a teenager, because his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was so ill and away so much. He died when Winston was barely twenty. Thereafter Jennie was completely on her own, and Winston was a handful.

But, then, Jennie was no ordinary Victorian mother, as David Lough makes clear in his Introduction. She combined a naturally warm and vivacious personality with considerable talents. She was a concert-standard pianist and was fluent in several languages, skills she had acquired during a childhood spent in New York, Trieste and Paris. This equipped her to survive the shock of marrying into the stiff, male-dominated world of the Victorian upper class and, indeed, to carve out a position among its top politicians, soldiers and intellectuals.

Jennie kept this position after her husband died and used her network of friends to pull all sorts of strings on Winstons behalf; at the same time, she tried to smooth his rougher edges without blunting his exuberance. Jennie also passed a spark of strong American independence onto Winston, which was to manifest itself in the darker years ahead when Britain stood alone and then later alongside her American allies after he persuaded them to enter the war. I love the tribute Winston gave his mother when he addressed the joint houses of Congress in December 1941 and said: I wish indeed that my mother, whose memory I cherish, across the vale of years, could have been here to see.

The striking intimacy of their long correspondence will give pause to those who assume their relationship was distant or strained. For his mothers eyes only, Winston confided his innermost thoughts on his strengths and weaknesses, on the senior generals and politicians of the day, and on his early attempts to devise his own political philosophy. Jennie told him whenever she thought he was wrong, at the same time describing evocatively the gilded lives of the Victorian and Edwardian elites among whose country estates she moved effortlessly as a popular guest.

All this we can now read in an exchange of sparkling letters spanning forty years. David Lough has assembled a wonderful collection that takes us through mother and sons shared successes and failures, love and disappointment, exhilaration and despair.

The result is not just wonderfully entertaining; it also sheds important historical light on a relationship that was pivotal in the growth of my great-grandfathers personality, political philosophy and moral courage.

RANDOLPH CHURCHILL

Crockham Hill

W INSTON CHURCHILL and his mother Jennie Jerome exchanged more than a thousand letters in the forty years between his sixth birthday and her death. Jennie was better at keeping her sons letters than he was at keeping hers, especially while he was fighting as a young man in north-western India, the Sudan and southern Africa. Nevertheless, I estimate that at least three-quarters of their letters survive; although many have found their way individually into biographies of either mother or son, they have never before appeared as an uninterrupted correspondence between the two.

I have had to omit some letters for reasons of space, but the majority of these omissions date from Winstons days at boarding school when he had to write a weekly letter home and he followed the schoolboys well-worn formula of weaving appeals for more pocket money or parental visits into tales of sporting or academic achievements. I have included a representative but far from exhaustive sample of the genre.

The many attractions of the letters exchanged between Winston and his mother Jennie struck me while I was researching an earlier book, No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money. It is not just the entertainment that two natural writers provide us as they express themselves to each other without reserve; nor is it just the historical light that each shines on the ruling elite at work and play in the years before the First World War, when Jennie in her own right was as well known a public figure as her son.

There are two additional attractions. The first is the insight that the letters offer into the curious mind of Winston Churchill as he develops his adult personality. By the time he was a teenager, his father Lord Randolph Churchill was seriously ill with a disease that doctors at the time treated as syphilis, although modern medical opinion is not so sure. So it was Jennie who took the strain of bringing up their difficult son and his brother Jack, six years younger.

Soon after Winstons twentieth birthday, his father died and Jennie became a single parent. From this moment onwards, she helped him to develop his education and his philosophy towards life. He confided intimately in her while testing out his increasingly assertive views about the military, social and political figures or controversies of the day. She was able to respond in kind because, being both well educated and socially well connected, she knew all the leading actors whom her son was precociously judging.

The second attraction is the almost operatic quality that the Churchills letters bring to the universal story of a mothers invincible love for a son, counterpointed by her gradual decline from the vibrant, young giver of life in the childs early days to the lonely, elderly burden that she felt herself to be in her later years.

In the first act of the drama, this mother struggles to cope with a wayward child while losing her husband inch by inch, in public, to a terrible disease. Following his death, the second act sees her subsume her ambitions into those of her son, deploying her many great gifts to advance his career. Then, in the third act, just as their joint endeavours are bearing fruit, she falls for the charms of a young suitor half her age. Despite many warnings against the alliance she marries him while her son stands loyally by.