The Long Road Back to China

By Carl Crow, edited by Paul French

ISBN-13: 978-988-18154-0-8

2009 Earnshaw Books

HISTORY / Asia / China

Spellings and punctuations are left as in the original edition.

First printing August 2009

Second printing January 2010

Thrid printing December 2010

EB026

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information contact

Published by Earnshaw Books Ltd. (Hong Kong)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF IMAGES

FOREWORD

BY P AUL F RENCH

IN August 1937 aerial terror came to Shanghai as bombs began to fall on the city. The situation in China escalated quickly by the end of the year Beijing was under Japanese control and the Rape of Nanjing had occurred, during which Japanese soldiers rioted through the city for six dreadful weeks. Carl Crow, an American journalist, advertising agent, author and man-about-town in Shanghai had been forced to leave Shanghais International Settlement and return to the United States. For some years he had been warning through his writing, speaking and letters of the coming threat to China from an increasingly aggressive and militaristic Japan. When the Japanese army arrived in Shanghai they remembered this.

At home his fame was growing. His 1937 book 400 Million Customers, a series of anecdotes and observations about China, the Chinese and foreign businesses in Shanghai, was a runaway bestseller. This was fortunate for Crow, as he had been unable to take more than a dribble out of his Shanghai bank account when he left and had had to leave his home, business and most of his possessions behind. Back in America more books followed as well as a national speaking tour to raise awareness of the deteriorating situation in China and appeal for greater public and political support from America for China in its struggle against Japan. Then in the spring of 1939 Crow was asked by Fulton Oursler, the editor of the liberal and pro-China Liberty magazine, to go to Chongqing to report on the wartime capital at the head of the Yangtze, from where the Chinese Nationalist government was staging its final stand against the Japanese invasion.

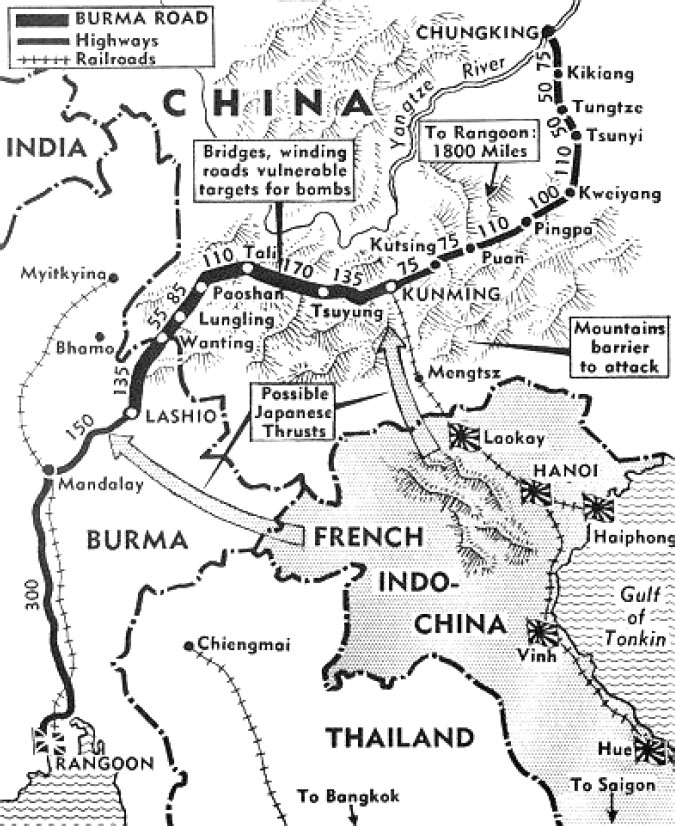

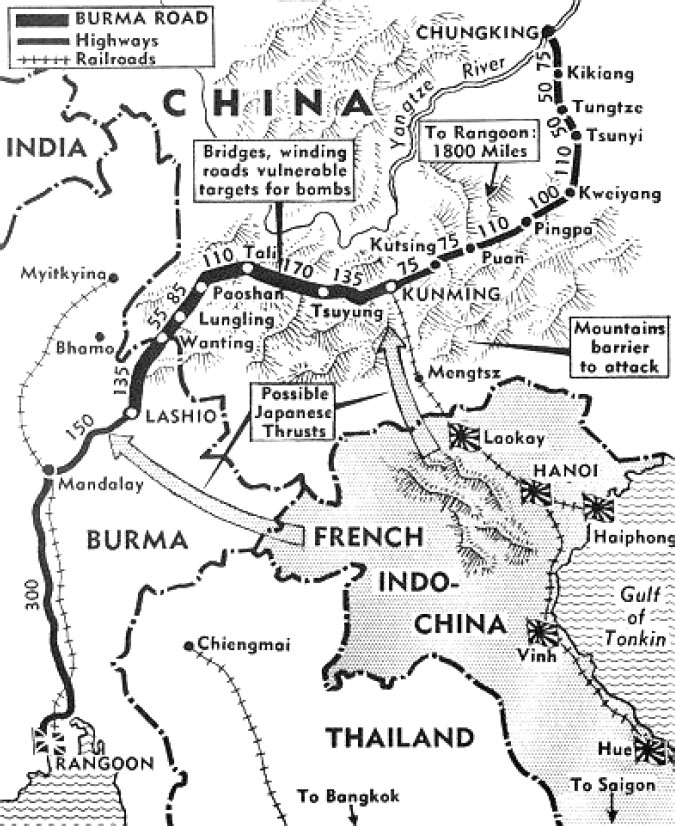

The obvious route by sea to Shanghai and then up the Yangtze to Chongqing was now problematic for Crow and so he decided to take the Burma Road. The new highway from the Burmese town of Lashio, through the Shan states and into Yunnan Province was itself, Crow believed, a vital weapon in Chinas armoury. To get to the Burma Road Crow sailed from New York to London and then flew to Rangoon, then still under British control.

When Crow arrived in Rangoon he found a city of simmering tensions and a nervous British administration. Burma and Rangoon had technically been part of British India, as Burma had been incorporated into the British Raj in 1886. However, in 1937 Burma had been designated a separate, self-governing colony. The British were still ultimately in control but tensions had increased between Burmese nationalists and the colonial administration as well as between the Burmese and the other ethnic groups the British had brought to Burma, notably Indians and Chinese. The vote for keeping Burma in India, or as a separate colony, had divided the populace and laid the ground work for the insurgencies that came after formal independence in 1948. The Japanese were believed to be stoking these political and racial tensions in Burma and Liberty had asked Crow to specifically look at this question. The benefit to Japan of a Burma in turmoil and chaos was obvious.

In 1939 the Burma Road was Chinas major lifeline for supplies of armaments and material to fuel the war effort as well as its major channel for exports to the outside world. The 717-mile Burma Road was rough and mostly mountainous; the more advanced engineering efforts of the US Army Corps of Engineers were to come later. In the spring of 1939 the Burmese portion of the road was little more than single track and the Chinese portion from the border with the Shan states to Kunming only slightly better. The sections from Kunming to the border had been built by 200,000 Chinese laborers throughout 1937 and 1938; repairs were constantly required, construction machinery virtually nonexistent and the monsoon rains unforgiving. The Burma Road continued to be a vital lifeline until the Japanese overran Burma in 1942, when the Allies began flying supplies over the eastern end of the Himalayas - the Hump and constructed the Ledo Road to connect Assam in India to the Road through territory in the far north of Burma that was still in Allied hands. Crows intention was to show the incredible efforts being made along the Burma Road by both the builders and the trucks that traversed it; to show how thin and fragile Chinas major line of communication with the outside world was.

Crows ultimate destination was Chongqing. By the end of 1937 Chiang Kai-shek had moved the government from Nanjing ever further inland; first to Wuhan and later to mountainous Chongqing. The city was then transformed steadily into a fortress retreat; from an inland port at the top of the Yangtze River to a heavily industrialized city able to create a war machine and absorb hundreds of thousands of refugees from Chinas coastal cities and occupied hinterlands to resist the Japanese invasion. In 1939 Chongqing was the most heavily bombed city in the world, over a year before the first wave of the Nazi Blitz was to hit London. From February 1938 to August 1943 Chongqing was almost constantly bombed more than 5,000 Japanese Imperial Air Force bombing runs with over 11,500 bombs dropped on the citys mostly civilian population. As Crow arrived in Chongqing on May 20th he witnessed the final days of the raids of May 1939 that killed more than 5,000 Chinese civilians a death toll previously unknown from aerial bombing.

Carl Crows diary of his trip from Rangoon, along the Burma Road and to Chongqing, provides a valuable source of information and first-hand experiences of the time. Most Burma Road memoirs either recall the Road before the war, when it was mostly a faded trade route between Burma and Western China or later when the Road had been significantly upgraded by the time the American correspondent Martha Gellhorn travelled the Road in 1941 Lashio to Kunming was still seven days by car but just three hours by plane. Crow traversed the Burma Road at both the roughest and most dangerous time still far from complete and yet being heavily used by endless streams of trucks pouring into and out of Western China. Crows diaries recall both the hazardousness of the Road as well as the life that continued along it and its supreme tactical importance to Chinas survival. The Burma Road closed in July 1940 and was not to reopen to Allied supply convoys until January 1945.

His recollections of Chongqing during May and June 1939 are also invaluable. As is usual for Crows writing style, they are at one and the same time both informative and partisan. Crow makes no bones about his unequivocal support for China in her fight against Japan and to do this he reveals the daily life of the wartime capital and its citizens life under constant air raids; nights spent in hastily constructed dugouts to avoid falling bombs; the death and destruction that reigned on the city and across Sichuan; the dead and the orphaned but above all these the stiff and stoic resistance of the Chinese people.

Next page