Surviving the Japanese Onslaught

Surviving the Japanese Onslaught

An RAF PoW in Burma

A Biography of William Albert Tate W.O. (Ret.) Royal Air Force Bomber Command 19381946

William Tate M.A.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Aviation

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright William Tate 2016

ISBN 978 1 47388 073 3

eISBN 978 147388 075 7

Mobi ISBN 978 147388 074 0

The right of William Tate to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Dedication

D uring the twentieth century, in both the First and Second World Wars, millions of allied forces personnel and civilians made incalculable sacrifices; many of whom died or were wounded. Western nations and their allies fought to secure our heritage, values and lifestyle for the benefit not only of their own generation, but future generations too.

In the course of the two world wars members of my family and relatives rallied to the call to do what they believed was their duty. The First World War saw my paternal Grandfather, William, fight predominantly on the Western Front while my paternal Grandmother, Elizabeth (Stoker), worked in a munitions factory for part of the war. My maternal Grandfather, Arthur Cox, became a member of the Military Police, now the Royal Military Police, and served on the Western Front. Two of my Great Uncles, Lesley and Robert (Bob) Stoker also fought on the Western Front.

Throughout the Second World War my father served in the Royal Air Force (Bomber Command) and his younger brother Robert with the Royal Corps of Signals. My paternal Grandfather served in the Air Raid Precautions (Search & Rescue) and my paternal Grandmother joined the Nursing Auxiliary Service. My maternal Grandfather worked on the railways, which were vital for the transportation of troops, resources and equipment to keep the war machine operating. Two of my mothers brothers, Reginald and Ronald Cox, both served in the British Army. Reginald served in Europe and the Far East, and Ronald served in the Middle East. My aunt June, the wife of Roy Cox, lost her father when she was 4 years old. Her father, John Cook, was posted to the Far East in 1941 and subsequently captured by the Japanese. John died as a Prisoner of War in Kuching, in Sarawak in 1945.

Of the 55,573 personnel of Bomber Command who made the ultimate sacrifice in the Second World War, I wish to mention two veterans. First is Paul Griffiths, a Co-Pilot, who first befriended my father in the Middle East but later died as a Prisoner of War of the Japanese in Rangoon, Burma. Pauls death haunted my father for the rest of his life. Second is Douglas Jeffrey who, at the time of the war, was a Navigator who died during a mission over Germany. Douglas is the cousin of David and Flora Edwards, two wonderful friends to my parents and, understanding better than many why my father suffered a breakdown, remained supportive of the Tate family.

To my publishers, for their commitment, professional advice and applications I have depended on I sincerely and gratefully acknowledge the following staff: Laura Hirst (Aviation Imprint Commissioning Editor), Karyn Burnham (Sub-Editor), Charles Hewitt, Lori Jones, Jon Wilkinson, and Matthew Blurton.

Finally I pay respect to the thousands of medical personnel including doctors, physiotherapists, nurses, orderlies, administrative staff, surgeons, psychologists, psychiatrists, dentists and orthodontists who have healed, and continue to heal, many veterans in both body and mind.

It is to the above that I remain deeply, and humbly, beholden.

Introduction

After capture and interrogation, with several beatings on my face and other parts of my body over two days, I was taken outside where Japanese soldiers were then ordered to raise and aim their rifles at me; I stood stiffly to attention fearing the worst.

William A Tate: April 1943

It has been written of men who have undergone a cruel captivity that the record thereof has never faded from their countenances until they died.

Charles Dickens

I n 1974, at 53 years of age, my father was admitted into hospital suffering a breakdown from a condition now extensively recognised as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. This ailment resulted from Williams incarceration between April 1943 and April 1945 as a Prisoner of War of the Japanese Imperial Forces in Rangoon Gaol in Burma (now Myanmar) during the Second World War. A number of symptoms associated with this illness William managed to control during the conflict and upon returning to civilian life, while others surreptitiously remained; nestled beneath the surface in a silent vigil, not spoken about, but waiting to erupt.

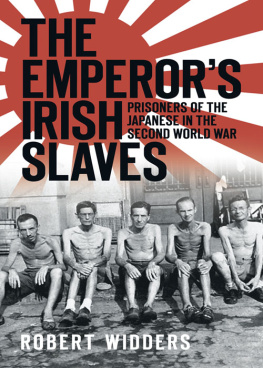

William was one of thousands of allied prisoners of war immutably scarred by the brutality and iniquitous butchery of their Japanese captors. This episode encompassed a systematic, intransigent policy of torture, beatings, solitary confinement, starvation, forced labour, insanitary and incommodious living quarters and virtually nonexistent medical facilities and stores. These deeds gave rise to, or compounded, a profusion of health problems among prisoners including beriberi, dysentery, cholera, malaria, physical deformities, amputation of limbs without anaesthetic, tropical ulcers and other skin infections. The physical plight of the prisoners was encumbered by the unrelenting anguish of their minds, endured by all prisoners of Japanese Prisoner of War camps, and from which many predominantly young men, once healthy in mind, spirit and body, were never to return home to their cherished ones. The day my father was liberated from Japanese military forces, he had been reduced to an emaciated 6 st 2 lbs, (approximately 39 kg), less than half his normal weight, and with a nervous system entwined in a state of infirmity. In spite of this horrendous ordeal, William forever considered himself a fortunate man to have survived.

My intent in 2015, during the seventieth anniversary of the cessation of the war, where unpleasant personal opinions regarding Japans war crimes may cause disapprobation, or be pressured into remaining hidden from the public domain, is to enlighten readers who may possess only a limited knowledge of the privations perpetrated by Japanese soldiers on their prisoners. These acts of callousness and cowardice, of a sanguinary disposition, did not belong to a civilised culture whatever apologia the Japanese people furnished Emperor Hirohito with, either preceding and during the war or, for that matter, in contemporary times.