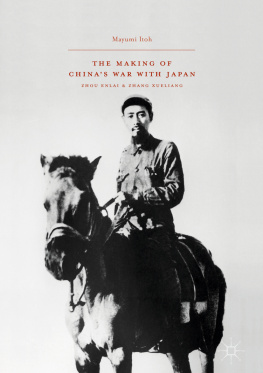

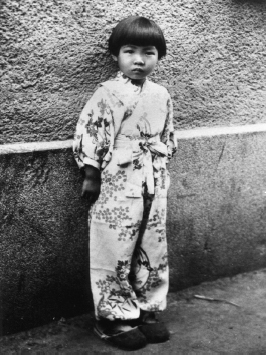

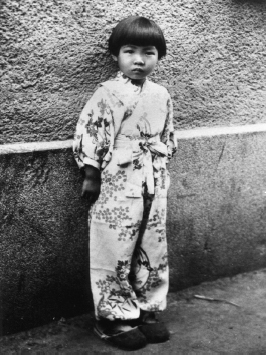

The author at age 5, standing beside the Shinkyo ether storehouse in Changchun.

This is the clothing she wore when entering the Qiazi no-mans land.

Published by

Stone Bridge Press

P. O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

TEL 510-524-8732

| Publication of this book has been supported by a generous grant from The Japan Foundation. |

2012 Homare Endo.

Originally published in Japan in 2012 as Chazu: Chugoku kenkoku no zanka by Asahi Shimbun Publications, Inc. English-language translation rights arranged by IBC Publishing, Tokyo.

English translation 2016 Michael Brase.

First English-language edition published 2016.

Cover design by Linda Ronan, incorporating a map of the city of Changchun prepared by U.S. Army Map Service in 1945 (Library of Congress).

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

p-ISBN: 978-1-61172-038-9

e-ISBN: 978-1-61172-925-2

Introduction

On October 1, 2012, China Central Television (CCTV) was showing the festive celebrations commemorating the sixty-third anniversary of the Peoples Republic. It would be the last such celebration in which Hu Jintao would preside as General Secretary.

Sixty-seven years earlier, on August 15, 1945, the day Japan surrendered to the Allied powers, the Chinese Communist Army led by Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung) and the Nationalist Army (Guomin-dang [Kuomintang] Forces) led by Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek) resumed their fight for national hegemony, a struggle that is often referred to as the Chinese Civil War.

During the Sino-Japanese War of 193745, instigated by Japans invasion of China, the Communist Army and the Nationalist Army sometimes collaborated, but with the defeat of Japan, all relations between the two combatants ruptured, and in 1946 civil war broke out in earnest.

At the time China was called the Republic of China, and Jiang Jieshi was the chairman of the national government. Thus, in the sense that the Communist Army was in rebellion against the national government, it can be said to have created a revolution. This explains why in modern-day China this struggle is often referred to as the Revolutionary War.

The Communist army emerged victorious and gave birth to todays Peoples Republic of China. This occurred on October 1, 1949.

I myself was caught up in the Chinese Civil War and struggle even today with ambivalent feelings toward China.

Until just recently, whenever I heard the opening notes of the Chinese national anthem, the March of the Volunteers, I instinctively stopped whatever I was doing and came to attention. This ingrained reaction was implanted in me when I was small. Whenever this happened, I couldnt help but shed sad tears over what I was doing.

There were days when Chinese children called me a Japanese Dwarf, a Japanese Devil, or a Japanese Dog, threw rocks at me, spit on me. It was as if I was the one who had invaded China. All this hatred and anger was directed at a little girl only ten years old or so. Their pent-up anger came in a furious barrage, as if to say its all your fault because youre a Japanese. There was nothing I could do but stand there, shrinking into myself.

My parents are not invaders, and neither am I, I wanted to say. Wanting somehow to prove my innocence, I would raise my voice loudly when singing the March of the Volunteers and other revolutionary songs. And somewhere in the back of my mind, I har-bored the faint hope that the new China would bring a brighter tomorrow.

Even though a great deal of time has passed since then, I would still come to attention, shouldering the burden of several decades, crying as I sang, my body trembling from sheer sadness.

* * * * *

But now its different.

Now I can be coldly objective; now I can feel an emotion close to wrath rise irresistibly within me.

In particular, the recent scenes on Japanese TV showing the anti-Japanese riots of September 2012, the figures of Chinese youths running amuck, has put even further distance between me and China. Seeing those faces twisted in hate, hearing the cries of Japanese Dwarf, Japanese Devil, Japanese Dog, I couldnt help but return to my ten-year-old self and feel as though I had been stabbed in the heart.

Although more than sixty years have passed since the war, young Chinese with no firsthand experience of the Japanese invasion are becoming more and more vehement and destructive in their anti-Japanese sentiments.

How long do they plan on prolonging this historical chain of events?

Then in October, as if someone had thrown a switch, CCTV suddenly began broadcasting a series of programs in which ordinary citizens were asked, Are you happy? Day after day it was this same question.

Many interviewees answer, What, am I happy? That goes without saying, doesnt it? After all, here I am, living a prosperous life in this wonderful country. My children and grandchildren have plenty to eat; theyre getting a good education, and

I realize that CCTV has purposely focused on what the Chinese government wants to hear. But still, listening to one proud smiling face after another say, Im happy, so happy, I cant help but have mixed feelings.

Then, all of a sudden, the announcer turns to the camera and asks the TV audience, Are you happy?

I immediately spring to my feet. Unhappythats what I am. How could I be anything else? Facing the TV, I shout this out in Chinese, challenging the announcer.

I had never reacted in this way before. It was unexpected, surprising even myself.

* * * * *

My life has been a long, continuous, agonizing struggle between China and Japan. But now I have had enough.

I was born in the city of Changchun, Jilin Province, in 1941, then called Xinjing, the capital of the Japanese puppet state of Man-zhouguo (otherwise known as the State of Manchuria or the Great Empire of Manchuria).

In 1946, owing to the intervention of U.S. special envoy George Marshall, the escalating Civil War was brought to a temporary halt and large numbers of Japanese were repatriated. This is known as the One Million Repatriation. It is said that the motive for American intervention was the fear that the Japanese remaining on the mainland would eventually come under the control of the Chinese Communist Party and be converted to Communism.

At this time Changchun was occupied by the Nationalist Army. In 1947 the Nationalist Party (Guomindang; Kuomintang) decided that all Japanese should be repatriated except for technicians with vital skills, who were to be detained. Since my father was a technician, he was not allowed to return to Japan. As a result of this policy, Changchun lost almost all of its Japanese residents.

When this repatriation had come to an end, Changchun abruptly came under siege by the Eighth Route Army (later the Peoples Liberation Army). Electricity and gas were cut off, drinking water unavailable. This was the beginning of the food blockade.

In 1983 I produced a piece of nonfiction writing called Fujori no kanata (Beyond the Unthinkable), which won the Yomiuri Womens Human Documentary Excellence Award. In one short week I had dashed down the thoughts that rushed to my mind. This was my first literary work for public consumption.

Next page