Contents

Guide

Dedicated to my Grandmother Florence Reid,

a survivor of the London Blitz.

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Penny Starns, 2018

The right of Penny Starns to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9031 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The process of writing this book has been greatly assisted by the military and civilian nurses who generously recounted their wartime experiences for my research. They include: Monica Baly, Mary Bates, Glenys Branson, Constance Collingwood, Gertrude Cooper, Ursula Dowling, Brenda Fuller, Anne Gallimore, Monica Goulding, Daphne Ingram, Anita Kelly, Margaret Kneebone, Sylvia Mayo, Kay McCormack, Anne Moat, Phyllis Thoms and Dame Margot Turner. The remarkable story of the latter is the subject of a separate book entitled Surviving Tenko. Dame Margots oral history testimony is held in the Imperial War Museum Sound Archive. The families of Rose Evans, Gladys Tyler, Florence Johnson and Grace Davis have also provided me with valuable source material.

Special thanks are due to the late Dr Monica Baly for her kindness, wisdom and guidance in the field of nursing history. Monica remained a very dear friend until her death in 1998. Thanks are also due to my PhD mentor Professor Rodney Lowe for his expertise in the field of welfare history. I am indebted to Captain Jane Titley, ARRC Matron-in-Chief of Queen Alexandras Royal Naval Nursing Service 199194, and Colonel Eric Ernest Gruber Von Arni ARRC of the Queen Alexandras Royal Army Nursing Service, for giving me valuable insights into the history and development of military nursing during the early stages of my research.

Archivists across the country have also assisted my research, especially those who are based at the Imperial War Museum, The National Archives, Royal London Hospital Archives, London Metropolitan Archives and the Royal College of Nursing Archives.

I thank my father Edward Starns for his consistent encouragement, and his vivid recollections of living through the Blitz. I am also grateful to those who have patiently listened to my ideas; these include Nigel Line, Michael and Rocha Brown, James and Lewis Brown, Joanna Denman, Catherine Nile and Margaret Taplin.

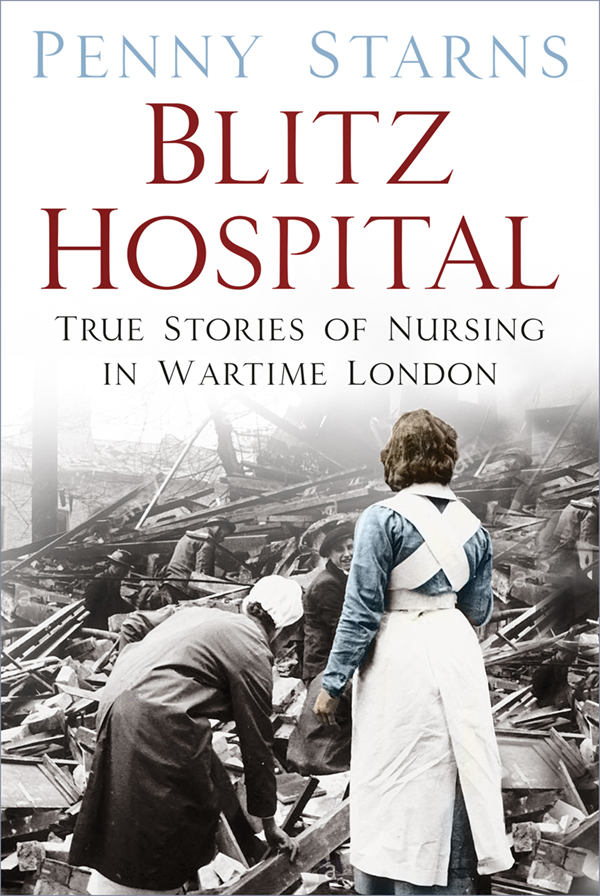

INTRODUCTION

In every war in our history, Britain has looked to the women to care for the sick and wounded. It is womens work. The nurses never let us down. Florence Nightingale lit a candle in the Crimea 85 years ago. The women of today have kept it burning brightly, not only in France, Egypt and Greece but in Poplar, Portsmouth, Liverpool, Hull and all the other battlefields on the Home Front.

Government recruitment poster

Imperial War Museum 536/172/K9540

As a Ministry of Health nurse recruitment poster acknowledged, what could be termed as being the front line during the Second World War was arbitrary. Medical staff were just as likely to be killed on the Home Front as they were when working within international theatres of war. Indeed, at the height of the Blitz, between September 1940 and May 1941, Home Front medical staff were far more likely to be killed or injured whilst administering emergency medical care than their international counterparts. As the German Luftwaffe subjected Britains major cities and ports to unremitting waves of aerial bombardment, doctors, nurses, first aiders, ambulance drivers and Air Raid Precaution workers constantly risked their lives to give urgent treatment to the severely wounded. Over 87,000 casualties were sustained during this period and city hospitals, especially in London, were working under extreme conditions. They were also experiencing acute staffing problems. A shortage of male doctors forced medical schools to open their doors to women, and nurses also extended their field of influence. A delighted senior nurse triumphantly wrote in the Nurses League Review of The London Hospital:

On March 1st the theatres were taken over by me and are now entirely run by the nursing staff. (Applause) This, as you will realise has meant a lot of reorganisation and it will take some time before they are running as we would wish. This, however, will mean that far more nurses can have theatre experience than was possible in the past.

But as nurses responsibilities increased, so did their workloads, and throughout the Blitz they worked at a furious pace. The diaries of London nurses reveal that they were confronted by a vast array of appalling injuries on a daily and nightly basis, charred bodies burnt black beyond recognition, gashed limbs and fractured spines. Gaping head injuries and bodies ripped apart by the force of bomb blasts. London skies were frequently aglow with burning buildings, as a nurse recorded on 7 September 1940: One early evening I noticed that the city skyline was a brilliant red it was just like a glorious sunset. Then I realised that if it was the sun, it was going down in the wrong place, because the glow was in the East.

Undoubtedly, the East End of London bore the brunt of the Blitz, which killed over 20,000 civilians in London alone. Survivors were cared for by staff at the citys hospitals, most of whom were an integral part of the governments official Emergency Hospital Scheme. Although source material is included from a variety of London hospitals, this book primarily follows the fortunes of two major London hospitals as they struggled to cope with mounting wartime casualties: St Thomas Hospital and The London Hospital (The Royal London from 1990 onwards). The diaries, letters and reports of medical and nursing staff highlight the many human stories of tremendous courage and hope that lived and breathed within the corridors, theatres and wards of Londons hospitals during the Blitz.

Background History of British Hospitals

By the early twentieth century, most British hospitals fell into two categories, depending on their funding arrangements. First were the voluntary hospitals, which were maintained by charitable donations; second, the local authority hospitals, which were funded by regional authorities. Voluntary hospitals tended to be prestigious institutions where medical men carved out their reputations and careers. On the other hand, local authority hospitals tended to be more lowly establishments, often feared by members of the public because of their long-standing associations with nineteenth-century workhouses. St Thomas and The London were both voluntary hospitals.