Contents

Guide

Oceans

Apart

Dedicated to the memory of Margaret Hill-Smith

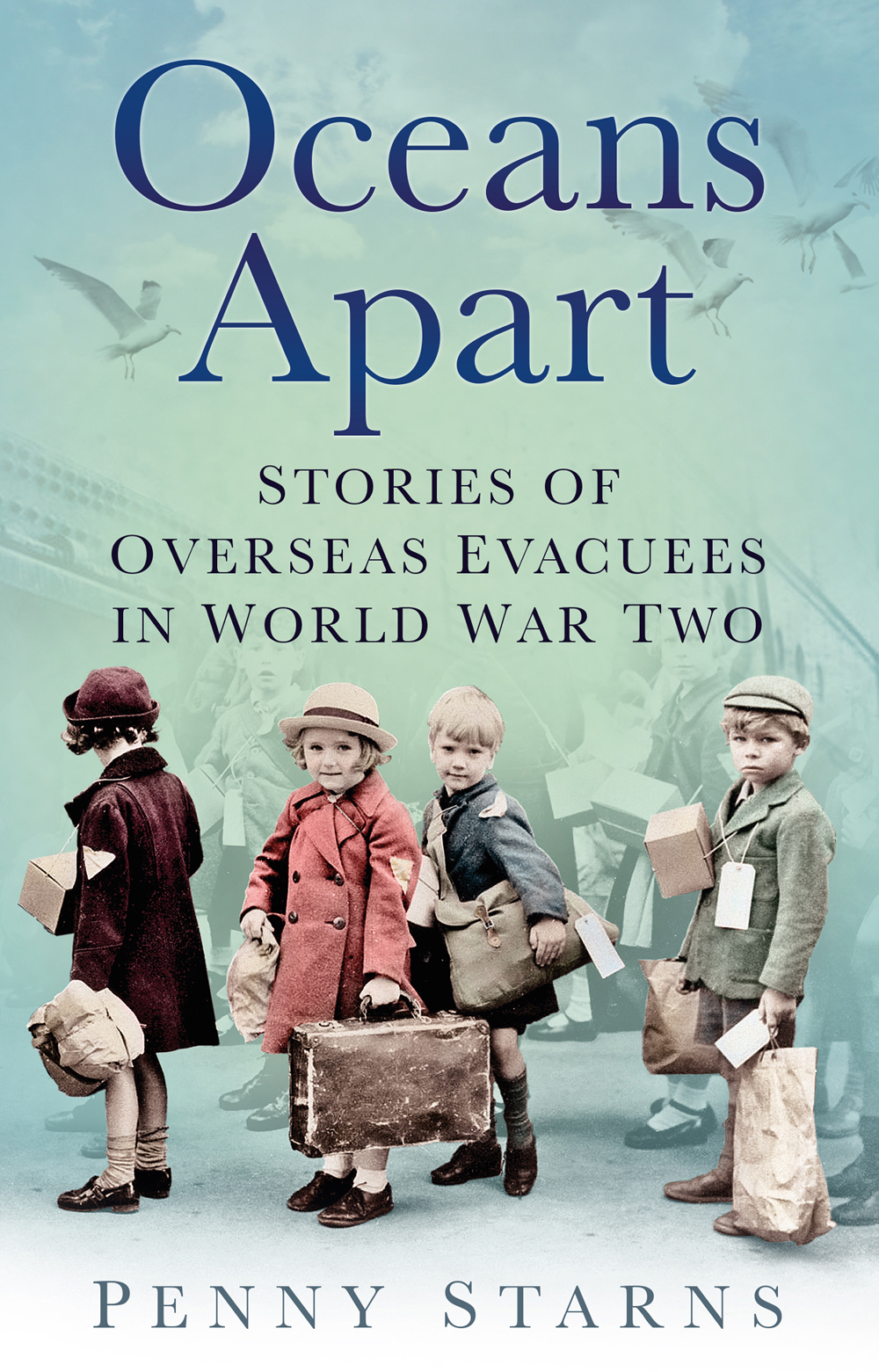

Front cover images: Monica B. Morris Archives; Wikimedia Commons.

Back cover image: Wikimedia Commons.

First published 2014

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Penny Starns, 2014, 2022

The right of Penny Starns to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 5472 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Firstly I would like to thank my editor Sophie Bradshaw and the production team at The History Press for their excellent work. I also thank my PhD supervisor Professor Rodney Lowe for initially guiding my research into child welfare. In addition I am very grateful to all of the ex-sea-vacs who recounted their individual experiences in the form of oral history testimonies, and to the various ships escorts, host family members and childcare professionals who documented their stories. These fascinating accounts have added a richness and depth to the overall text. Margaret Bush deserves a special thank you for generously allowing me to include her personal story and unique images of her childhood in Canada. I also extend my gratitude to archivist Anthony Richards of the Imperial War Museum, who assisted my research, and to the many archivists who helped me to find further information in both the national and county archives across the country, and beyond into the realms of empire.

I thank my father Edward Starns for his love and continuing support, and my friends Timothy Dowling, Maggie Keech, Deborah Evans, Jo Denman, and Catherine Nile for their encouragement. I also appreciate my brother Christopher for his previous research assistance. Finally I thank my sons and grandchildren for their love and humour.

Therell Always Be an England

I give you a toast Ladies and Gentlemen

I give you a toast Ladies and Gentlemen

May this fair land we love so well

In dignity and freedom dwell

While worlds may change and go awry

Whilst there is still one voice to cry!

Therell always be an England

While theres a country lane

Wherever theres a cottage small

Beside a field of grain

Therell always be an England

While theres a busy street

Wherever theres a turning wheel

A million marching feet

Red white and blue

What does it mean to you?

Surely youre proud

Shout it out loud

Britons awake!

The Empire too

We can depend on you

Freedom remains

These are the chains

Nothing can break

Therell always be an England

And England shall be free

If England means as much to you

As England means to me

Therell Always Be an England was composed and written by Albert Rostron Parker and Charles Hugh Owen Ferry in the summer of 1939. The song became a hit for Vera Lynn during the Second World War, and it was adopted by the sea-vacs as their signature tune when leaving and approaching ports, and most poignantly when they were in their lifeboats awaiting rescue after their ships had been torpedoed by the enemy.

Introduction

Much has been written in recent years of the horrors of forced child-migration schemes; of children who were sent to the Dominions in order to work the land and boost population numbers. Often they were badly treated and exploited in the process. The story of children who were sent overseas during the Second World War however, was dramatically different. This cohort of children were generally fussed over, feted, adored and completely spoilt; they were viewed as special and treated accordingly. Known as sea-vacs, the history of these extraordinary youngsters is complex and controversial. The subject matter embraces the pressing concerns of the British at war, but also highlights the prevailing social attitudes with regard to class distinctions, child welfare, eugenics, religious affiliations and national identities. In the wider sense, the topic also sheds light on the shifting sands of competing social and political ideologies within the British Empire and the strenuous efforts that were made to strengthen and uphold traditions of colonial rule. Indeed, during the months leading up to the war some sections of British society chose to make full use of colonial ties and were already abandoning the country faster than rats leaving a sinking ship.

Upper-class British families began sending their children overseas in the latter part of 1938. Some already had family connections in the United States of America or in the Dominions, and were therefore able to rely on a reasonable welcome and accommodation for their children. By virtue of their affluence, all of these families were able to secure private shipping arrangements. According to The Times newspaper, thousands of these wealthy children had been shipped abroad in the months leading up to the declaration of war, and during the forty-eight hours immediately before this declaration 5,000 adults and children had fled from Southampton to the United States. Furthermore, long queues of chauffeur-driven cars, the titled and well-to-do accompanied by their valets and maids staggering under the weight of their luggage, became a prominent feature of all British ports. Alongside these privately secured escape routes, companies such as Kodak and Ford established their own evacuation schemes. Notable academics in Canada and the US even operated eugenically motivated evacuation programmes designed to support and preserve the intellectual elite by persuading scholars to offer homes to the children of Cambridge or Oxford dons.

Naturally, this rapid exodus of the British social, financial and intellectual elite prompted deep resentment in other sections of society. The average shipping fare from Britain to the United States was somewhere between 15 and 18. For around 75 per cent of the British population this amount constituted their monthly wage, and effectively priced them out of the market in terms of sending their children abroad. However, by April 1940 public criticism of elitist escape routes, combined with a significant shift in wartime circumstances, galvanised the government into action. While politicians hotly debated the pros and cons of sending children overseas, it was the imminent threat of invasion that drove policy decisions at this stage. Consequently, a Childrens Overseas Reception Board was established, and British children were sent to far-flung corners of the empire.