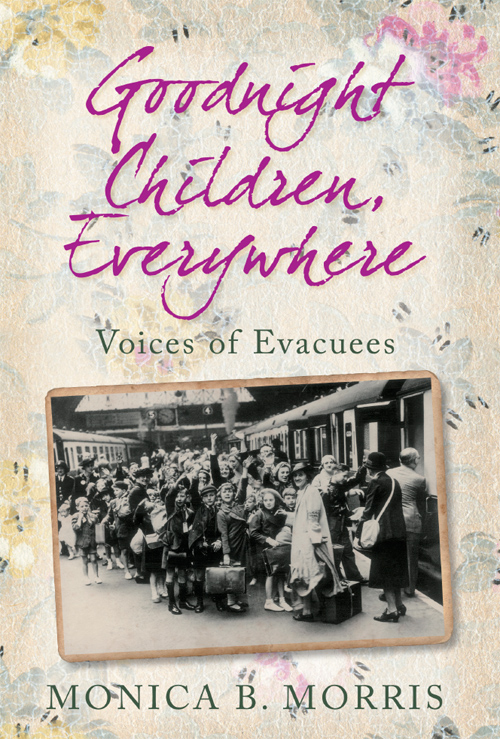

Goodnight

Children,

Everywhere

Goodnight

Children,

Everywhere

Lost Voices of Evacuees

MONICA B. MORRIS

First published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Monica B. Morris, 2009, 2011

The right of Monica B. Morris, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7568 4

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7567 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Ebook compilation by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Acknowledgements

A book is never solely the work of one person. I am indebted, first, to Diz White, my friend and colleague, author of Haunted Cotswolds and Haunted Cheltenham, whose cheerful enthusiasm kept my nose to the grindstone or, rather, my fingers on the computer keys even when I would rather have gone fishing. Thanks, also, to my walking buddy, Maureen Bailey, with whom I shared many of my ideas when we were hiking in Bronson Canyon, and who always asked pertinent and thought-provoking questions.

Without the men and women who sat patiently and told me their stories, I would have no book. Thank you all; I am eternally grateful. And to Nicola Guy of The History Press goes my appreciation for her optimism and advocacy; you are a treasure.

Finally, to my husband: it isn't easy being married to a writer!You may hope that she is simply sharing a meal with you as you look at her across the dining table, but you know she is editing passages and juggling facts and figures, and mixing moonbeams and metaphors in her head! So thank you Clark, for your understanding, patience and encouragement.

Images

Many thanks to the Associated Press, the Imperial War Museum and Diz White for allowing the reproduction of the images in this book.

Note: Some names have been changed or omitted for protection of individual privacy.

Introduction

The beginning of September 1939 saw a unique event in Britain's history.

Never before had millions of children close to a million just from London alone been moved from the cities to the countryside in the space of three or four days, and without a single accident or casualty. Operation Pied Piper, as this Government Evacuation Scheme was dubbed, has been described as the largest, best-prepared and most minutely organized movement of mothers and infants, schoolchildren and others ever conceived in peacetime. No one has ever seen anything quite comparable. And although this was not the only time during that era that the children were transported from place to place there was another evacuation, Operation Trickle, in October 1940 to take the children away from the Blitz, and still another, Operation Rivulet, in the autumn of 1944 it was the one at the onset of the war that seared minds and spirits most; it lingers still in the memory.

Most of the people telling their stories in this book make some mention of their parents seeing them off on the buses or deliberately not seeing them off. Some, including myself, claim that parents had been told to stay away from schools and other embarkation points to avoid displays of emotion that might slow down the process. Others mention that their mothers walked with them to school and helped them to carry their luggage. I wondered, therefore, if there had been any official policy and learned that while parents were generally not to be allowed on railway platforms, head teachers appear to have made individual decisions about the parents of their students making their farewells at their schools.

Margaret Gaskin, in her book Blitz, tells of the headmistress of the London County Council's Stoke Newington Junior and Infant Schools who had called a joint emergency meeting for parents at the start of September 1939, on the eve of the children's departure. One teacher recalls how solemn it was in the school hall, packed with grim-faced parents who listened in silence as the headmistress ran through the drill for the following day.

You will want to see them off, she began. She then gently requested that they stand around the playground walls and wave the children off cheerfully as they marched out. Shed your tears after they have left, she urged. She also reminded them to appreciate the sacrifices that the teachers were making. They, too, were leaving their homes and their families to shoulder the serious responsibility of looking after other people's children. Her advice was followed to the letter. The parents who came to the school smiled through their anguish and the children went off cheerfully. As the children left the playground and climbed onto the buses, the parents all waved and so did the children. It was a most moving sight, the teacher continued. the children and their parents showed great courage. The only tears I saw shed that day were those of the young bus driver who wept all the way to Finsbury Park where we disembarked.

That parents were so cooperative as their children were taken away to unknown destinations, perhaps never to be seen again, is testament to the trust that parents put in the school staff and in the government. Further, they had been persuaded that their sacrifice was warranted. This mass exodus of September 1939 had been in the planning since the early 1930s. It was anticipated that the bombing would begin as soon as war was declared, and there were predictions of as many as 4 million civilian casualties in London alone.

As early as 1922, after the air threat from Zeppelins, Lord Balfour had suggested that the capital of the Empire would be subjected to unremitting bombardment of a kind that no other city has ever had to endure It was felt that the inferior housing of poor people would be the first to collapse and as many children from the cities, especially from the East End of London, lived in sub-standard dwellings, it was vital to get them into safer areas as quickly as possible. The rich were thought to be able to fend for themselves. They could leave the cities as families or they could send their children to America or to the colonies.

The estimates of casualties, as it turned out, was something of an exaggeration. According to Richard M. Titmuss, from the onset of the Blitz on 7 September 1940 when the bombing began, until 1 January 1941, some 13,596 Londoners were killed and 18,378 were severely injured. On 10/11 May 1941, a further 6,487 were killed and 7,641 were injured. These are horrifyingly large numbers but they are far from the many millions of casualties estimated.

Further, the bombardment did not begin with the declaration of war, as was predicted. The Blitz began a whole year later, in September 1940, and during this period, known as the phoney war, when nothing was happening, thousands of homesick children had returned to the cities. As early as November 1939, more than 6,000 children a week were returning to London alone, and by the summer of 1940, half of all that city's children were home I was one of them and their parents had to be persuaded to send them away again.