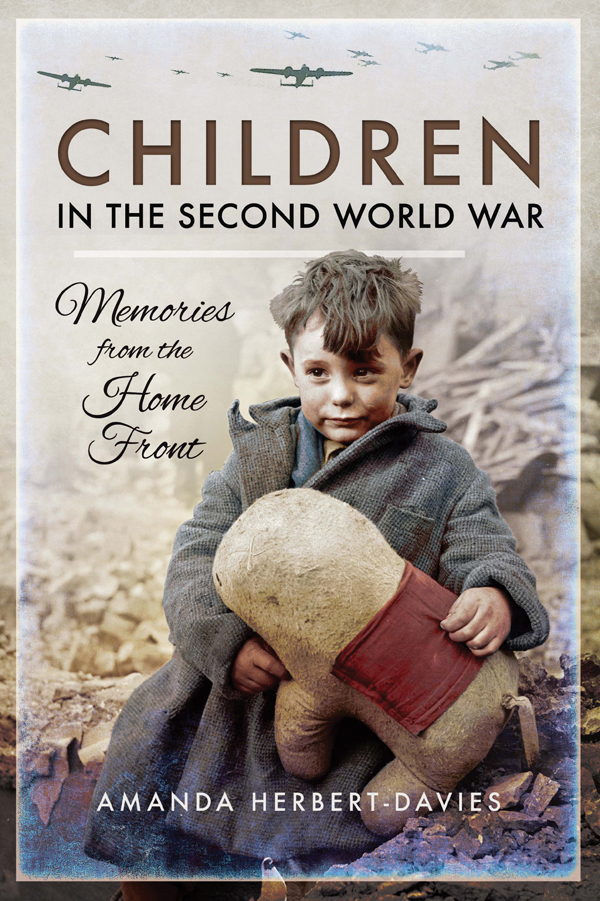

Children in the Second World War

To my children Eleonore and Eloise

Children in the Second World War

Memories from the Home Front

Amanda Herbert-Davies

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Amanda Herbert-Davies, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47389 356 6

eISBN 978 1 47389 358 0

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 357 3

The right of Amanda Herbert-Davies to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

List of Plates

A twelve-year-old girl helping to dig a trench for air raid protection in Kent, 1939. (D. Rice)

A homely Anderson shelter. (P. Tollworthy)

A sketch of her familys Anderson by Christine Widger, aged twelve, drawn while sitting in the shelter during a doodlebug attack .

A brick surface shelter built at the bottom of a garden in Kingsmead Avenue, Tolworth, Surrey. (E. Gardener)

Evacuees label. (W. Hayle)

Phyl Jones, privately evacuated from East London with her siblings for the duration of the war .

Muriel Booth, aged eleven, who was evacuated on a Thames paddle steamer .

Muriel Booths plea to come home from evacuation .

Kitty Levey (right) and her sister, CORB evacuees, ready to depart from Lancashire to South Africa .

Jo Veale from Birmingham who was convinced she was going home on Monday. She did not return home for six years .

Christine Widger, evacuated from Kent to Lancashire, kept in touch with her Lancashire teacher for the next fifty-seven years .

Yorkshire boy Ernest Tate, spy-watcher and unofficial member of Leeds ARP .

Daphne Hackett, aged eleven, whose family befriended prisoners from Thames Ditton POW Camp .

German prisoners at Long Ditton POW Camp, Greenwood Road, Thames Ditton, Surrey. October 1946. (Iain Leggatt)

Dorinda Simmonds of Ealing, London, black-market butter girl .

Derek Clarks school, semi-demolished overnight by a doodlebug in 1944 .

A little boy in Kent playing with his fathers ARP kit. (M. Jones)

Iain Leggatt playing war games, 1942 .

Alan Starling (left), underage member of the 3rd Battalion Renfrewshire Home Guard, Scotland .

Geoff Creece, GPO messenger boy in Portishead during the Bristol Blitz .

John Bones in uniform as Flight Sergeant in No. 308 Squadron Air Training Corps, Colchester .

Joyce Garvey (1942), who helped a mother give birth in an air-raid shelter, member of Birmingham ARP from the age of sixteen .

Jean Wilson, member of Friern Barnet Girls Training Corps, London .

Jean Wilson wearing her St John Ambulance cadet uniform .

Myfanwy Khan with her older sisters in the garden of her home in Exeter .

The ruins of Myfanwy Khans home after the Exeter blitz, 1942 .

Margaret Hofman, whose family fled the docklands of London during the Blitz .

Sketch of a doodlebug by Jeff Nicholls who was an industrial spotter in London for the Alarm within the Alert .

John Pincham (left) and his brother at home in Wimbledon Park the year before they were bombed-out .

Bomb-damaged houses in John Pinchams street, 1944, which had to be guarded from looters .

VE Day street party in Rothsay Road, Gosport. (M. Brien)

Introduction

During the Second World War, Britain was a war zone. Over 60,000 civilians died on the Home Front due to enemy action, millions of homes were damaged or destroyed, and mass migration was necessary to save the vulnerable. The last generation able to give a living testimony of life in Britain during this, one of the countrys most tumultuous periods in history, are those who were children. On the Home Front, war pervaded every aspect of life. As a consequence, children from the very young to teenagers were inextricably involved in the war effort and even warfare itself. There was no child who was not, to a greater or lesser degree, untouched by the exceptional conditions of the time .

This book describes the Home Front from the childrens perspective, focusing on those experiences which left the deepest impressions. From the cataclysmic wail of the first air-raid siren to the Victory bonfires that scarred the backstreets, these recollections present a comprehensive picture of childhood in Britain throughout the Second World War, as remembered by those who lived it. The experiences of these children who came from all over the country, from every class, are as diverse as the individuals who tell them .

For some children, particularly the younger ones, the war did not detract from a happy childhood because, to them, war was normal. Though conscious of what was going on, they did not have the deeper concerns their parents had. Protected by the optimism of youth which believes tragedy is a lifetime away and dying is for the old, young children were free to find excitement and thrills in war. The fear felt during bombing raids was, as described by one boy, like being on a rollercoaster ride: it belonged to the moment and then it was over; until the next time. Some of these children even considered their wartime childhood to have been an exciting journey, one which did not last long enough. The popular picture of children on the Home Front presents a childhood like this, one which shows childrens attraction towards and the ability to cope with the conditions of war. This is verified by the overall impression of childrens experiences which, even when set within the context of war, is one of the cheerful optimism of youth, that ability of children to find adventure and enjoyment in the world around them. The war, with all its restrictions, provided plenty of opportunity for that .

Whether living in the battleground of a Birmingham housing estate or the war-torn tenements of Glasgow, children adapted to war. Gasmask fitting, a trial that no child could escape, evolved into gas-mask couture with fancy designer cases; the blackout, so intrusive in the lives of adults, gave the freedom of unsupervised play. By day, school lessons were undertaken in semi-derelict schools, greenhouses and tin sheds, while nights were spent in the wartime bedrooms of underground shelters, crypts and caves. Shelter-run etiquette, secret butter runs and auditory bomb-tracking were part of daily life. From spy catching missions to running business ventures with the local POWs, children embraced life on the Home Front. Even that which was designed to cause terror aerial bombardment provided inspiration for creative enterprises: bomb craters made for speedways; shrapnel became the new playground currency; home-made explosives were produced in backyard sheds. There was also the opportunity for direct involvement in civil defence, positions which gave responsibility and pride. Child messengers sped through bombed cities at night, young firefighters stood guard on the top of seven-storey mills during air raids, and underage boys patrolled the parish armed with only the vicars First World War pistol .

Next page