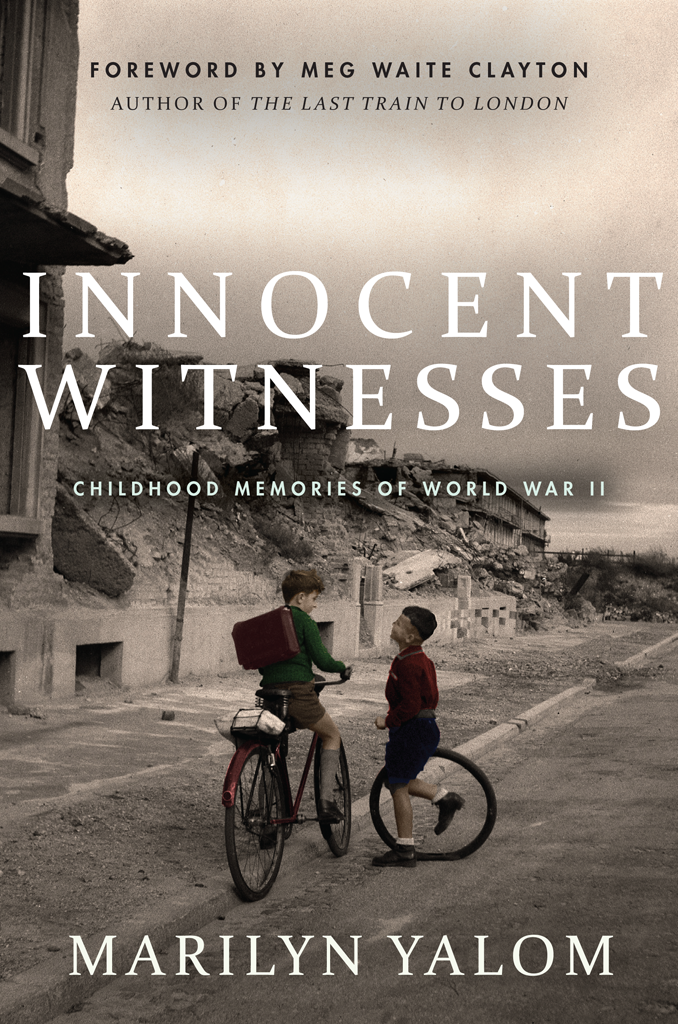

INNOCENT WITNESSES

Childhood Memories of World War II

MARILYN YALOM

With a Foreword by Meg Waite Clayton

Edited by Ben Yalom

REDWOOD PRESS

Stanford, California

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

2021 by Marilyn Yalom. All rights reserved.

Foreword 2021 by Meg Waite Clayton LLC. All rights reserved.

Afterword 2021 by Ben Yalom. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Yalom, Marilyn, author. | Clayton, Meg Waite, writer of foreword. | Yalom, Ben, editor.

Title: Innocent witnesses: childhood memories of World War II / Marilyn Yalom; with a foreword by Meg Waite Clayton; edited by Ben Yalom.

Description: Stanford, California : Redwood Press, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020026964 (print) | LCCN 2020026965 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503613652 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503614048 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 1939-1945ChildrenEurope. | World War, 1939-1945EuropePersonal narratives. | LCGFT: Personal narratives.

Classification: LCC D810.C4 Y35 2021 (print) | LCC D810.C4 (ebook) | DDC 940.53092/53094dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026964

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026965

Cover design: Rob Ehle

Cover photo: Traces of the war, Freiburg after 1945. akg-images, Ltd.

Text design: Kevin Barrett Kane

Typeset at Stanford University Press in 11/16 Constantia

CONTENTS

, by Meg Waite Clayton

, by Ben Yalom

FOREWORD

MARILYN YALOM was a community-maker, a bringer-together of people, a supporter of others, and a writer about the kind of friendship and love that rested at the core of her unfathomably generous heart. To all she did, she brought her particularly intense and careful way of listening, a tireless championing of others, and a delightfully mischievous sense of humor. All three are evident in the pages of this new booka book which might come as a surprise to readers who know her only through her writing. It was in fact, at first glance, a bit of a surprise to me.

Marilyn was a feminist, early and often and wholeheartedly. She was one of the organizers and a director of what is now the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University, its real, on-the-ground working founder, historian Edith Gelles says, and Deborah Rhode, a subsequent director, calls her its true leader. As the institutes director, Marilyn championed women generally and individually, bringing in visiting scholars and organizing conferences and programs to amplify female voices.

An admirer of the female-driven French salon culture of centuries past, Marilyn also hosted, with poet Diane Middlebrook, a salon of San Francisco Bay Area women journalists, novelists, poets, nonfiction writers, and academics across all fields. Men were invited only once each year. I wont soon forget the horror I felt when, during a poetry reading at the first salon Marilyn invited me to attend, I was moved to quietly weeping among all these swanky strangers. But she invited me back, and I dont believe I launched a novel afterward without Marilyn hosting a salon to celebrate, one of the many ways she supported so many of us. Silicon Valley historian and salonnire Leslie Berlin recalls how, when she was a lowly graduate student... not in Marilyns department, in her field, or even working in the same century, Marilyn often checked in to see how her dissertation was coming and, later, was always there with a kind word when I had something published somewhere. German-born author Renate Stendhal describes the salon as something shed never seen outside Europe... a place to call home in terms of warmth, hospitality, intellect, culture, community, writing (and baking!).

Marilyns prior books, too, largely focused on women. Since her 1985 debut, Maternity, Mortality, and the Literature of Madness, her titles alone tell us we will be reading about female lives. Blood Sisters. A History of the Breast. A History of the Wife. The Social Sex: A History of Female Friendship. Compelled to Witness: Womens Memoirs of the French Revolution.

In Birth of the Chess Queen, she explores the transformation of the sole female piece on the board, originally the games weakest, into its strongest power. It is something Marilyn herself did in life and in her work: not just connecting us with each otherconnecting women, especiallybut also lifting us up.

Of course, many of these earlier books, as well as the last three published in her lifetime, are as steeped in history as is this new one. Her The American Resting Place, a collaboration with her photographer son, Reid, examines four hundred years of history through a look at burial grounds. How the French Invented Love takes readers on a journey through centuries of French literature. The Amorous Heart explores the heart as metaphor and icon across two thousand years.

But a collection of first-person narratives of people who were children during World War II?

Why this book? Why now?

In its final chapter, When Memory Speaks, Marilyn tells us, I suspect that I have written this book, long after the end of World War II, because I have carried a lifelong sense of debt to the millions who suffered instead of me. And I despair as I see how many others continue to suffer.

Here, she does what she always did so well in her writing and in life: she brings diverse elements together, and finds connection. She uses those connections to explain and explore. In exploring memories from nearly a century ago, she allows us a greater understanding of what it means to be human in this world today.

This is a Marilyn Yalom book, so have no fear: even on this literary turf of war story so often dominated by male voices, she finds space for female experience. Three pieces are written by women, including one by Marilyn herself. And the pieces by men, too, include stories of motherhood.

But more importantly, she explores that other theme of Birth of the Chess Queen: the conversion of weakness into strength. Here, she demonstrates that transformation through the stories of people who lived through World War II as vulnerable children and emerged to become important thinkers, teachers, and leaders. Not flawless. Not undamaged. Not without weaknesses. But ultimately strong.

In the opening memoir, A Sheltered Vision, Marilyn considers her own childhood in Washington, DC, during the war, where it never occurred to her that Jews could be a special target of attack. She ate less sugar but never went hungry. Her behavior was questioned by a teacher who frowned upon her mother working in the war effortcriticism Marilyn even as a child shrugged off, a lovely prelude to her own partnering with Irvin Yalom to raise four children while they pursued dual careers. The innocence of her childhood was shattered only after the war ended, when her family learned that her aunt, uncle, and cousin in Poland had died in a concentration camp. Living in France herself seven years later, she saw the lasting devastation wreaked by war.

Philippe Martial was five and had newly lost his father to paratyphoid when his family moved from the city of Djibouti in what was then French Somaliland back to his grandparents Normandy home just before the war began. He writes in Under German Occupation of his experience living through the war in Fleury-sur-Andelle, near the city of Rouen which was nearly destroyed by Allied bombs. German soldiers occupied and ravaged their home. He grew up cold and hungry. His mother used burnt wood ash for soap. His is a childhood any of us would grieve to have our sons and daughters experienceyet one he is apologetic for mentioning, given what happened to others in the Holocaust.