How The French Invented Love

Nine Hundred Years of Passion and Romance

Marilyn Yalom

N EITHER YOU WITHOUT ME, NOR I WITHOUT YOU

Ni vous sans moi, ni moi sans vous

Le lai du chvrefeuille, Marie de France, twelfth century

Contents

Ablard and Hlose, Patron Saints of French Lovers

Courtly Love: How the French Invented Romance

Gallant Love: La Princesse de Clves

Comic Love, Tragic Love: Molire and Racine

Seduction and Sentiment: Prvost, Crbillon fils, Rousseau, and Laclos

Love Letters: Julie de Lespinasse

Republican Love: Elisabeth Le Bas and Madame Roland

Yearning for the Mother: Constant, Stendhal, and Balzac

Love Among the Romantics: George Sand and Alfred de Musset

Romantic Love Deflated: Madame Bovary

Love in the Gay Nineties: Cyrano de Bergerac

Love Between Men: Verlaine, Rimbaud, Wilde, and Gide

Desire and Despair: Prousts Neurotic Lovers

Lesbian Love: Colette, Gertrude Stein, and Violette Leduc

Existentialists in Love: Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre

The Dominion of Desire: Marguerite Duras

Love in the Twenty-first Century

H ow the French love love! It occupies a privileged place in their national identity, on a par with fashion, food, and human rights. A French man or woman without desire is considered defective, like someone missing the sense of taste or smell. For hundreds of years, the French have championed themselves as guides to the art of love through their literature, paintings, songs, and cinema.

We English speakers often turn to French expressions for the vocabulary of love. We refer to tongue-locked embraces as French kissing. We have adopted the words rendezvous, tte--tte, and mnage trois to suggest intimacy with a French flavor. Our words courtesy and gallantry come directly from the French, and amour doesnt need to be translated. Americans, like much of the world, continue to be fascinated with anything French that promises to improve our physical appearance or our love lives.

O ne defining feature of love la franaise is its forthright insistence on sexual pleasure. Even older French men and women today cling to a vision of love grounded in the flesh, as indicated by a recent poll of American and French citizens aged fifty to sixty-four. According to a study published in the JanuaryFebruary 2010 issue of AARP The Magazine , only 34 percent of the French group agreed with the statement that true love can exist without a radiant sex life, as compared to 83 percent of American respondents. A 49 percent difference in opinion on the need for sex in love is a startling statistic! This French emphasis on carnal satisfaction strikes tighter-laced Americans as deliciously naughty.

Moreover, the French idea of love includes the darker elements that Americans are reluctant to admit as normal: jealousy, suffering, extramarital sex, multiple lovers, crimes of passion, disillusion, even violence. Perhaps more than anything, the French accept the premise that sexual passion has its own justification. Love simply doesnt have the same moral overlay that we Americans expect it to have.

From the medieval tale of Tristan and Iseult to modern films like Mississippi Mermaid , The Woman Next Door , and Leaving , love is represented as a fatum an irresistible fate against which it is useless to rebel. Morality proves to be a weak opponent when confronted with erotic love.

In this book I trace lamour la franaise love French-stylefrom the emergence of romance in the twelfth century until our own era. What the French invented nine hundred years ago, and have been reinventing through the ages, has traveled far beyond the borders of France. Americans of my generation thought of the French as purveyors of love. From their books, songs, magazines, and movies, we concocted a picture of sexy romance that was at odds with the airbrushed 1950s American model. How did the French get that way? This book was written to answer that question.

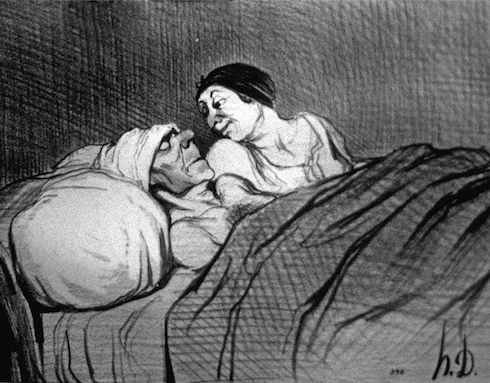

Two kinds of loving. Paintings by Edouard Manet and Honor Daumier. Photograph copyright Kathleen Cohen.

Ablard and Hlose, Patron Saints of French Lovers

T HROUGHOUT MY LIFE, G OD KNOWS, IT HAS BEEN YOU, RATHER THAN G OD, WHOM I FEARED OFFENDING, YOU, RATHER THAN H IM, I WANTED TO PLEASE.

Hlose to Ablard, circa 1133

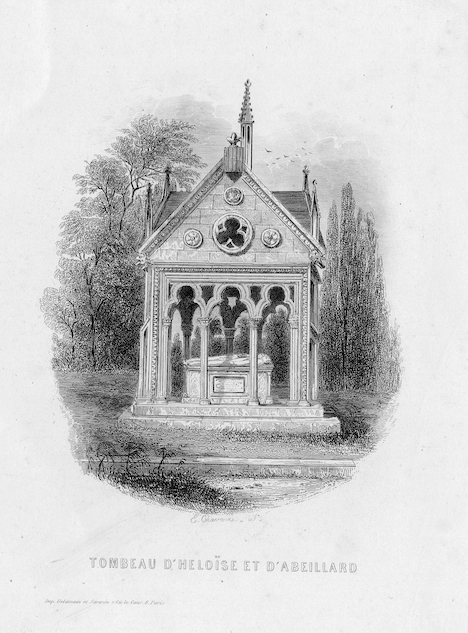

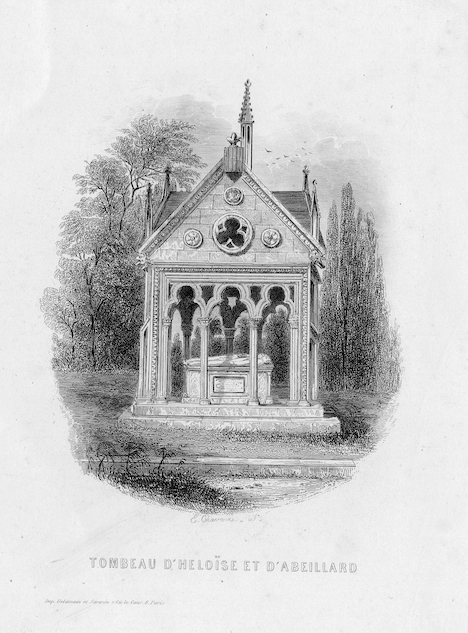

Tombstone of Ablard and Hlose in Pre-Lachaise Cemetery. Nineteenth-century engraving.

A blard and Hlose are as familiar to the French as Romeo and Juliet are to Americans and Brits. This pair of lovers, living in the early twelfth century, left behind a story so bizarre that it reads like a gothic novel. The astonishing letters they wrote each other in Latin and Ablards autobiography, Historia calamitatum (The Story of My Misfortunes), have become charter texts in the history of French love.

Ablard was an itinerant cleric, scholar, philosopher, and the most popular teacher of his age. He became famous in his twenties and thirties for his speeches on dialectics (logic) and theology. And his good looks didnt hurt. Like rock stars today, he brought out adoring crowds in his appearances as a public speaker. Before the establishment of universities in France, there were urban schools that rose up around celebrated scholars, and the one Ablard created in Paris brought together students from every part of Christendom.

Hlose, the niece and ward of a church canon living in Paris, was already renowned in her teens for her brilliant mind and advanced learning. By then, she had already mastered Latin and would go on to become conversant in Greek and Hebrew. Attracted by her singular talents, Ablard devised a surefire method to seduce her: he would lodge in the canons house and give her private lessons. It did not take long for them to fall into each others arms and develop a mutual, searing passion.

During the winter of 11151116, when they first became lovers, Hlose would have been barely fifteen and Ablard around thirty-seven. Yet he claimed to have been celibate before their encounter and was totally unprepared for the overpowering force of their shared entrancement: With our books open before us, more words of love than of our reading passed between us, and more kissing than teaching. My hands strayed oftener to her bosom than to the pages; love drew our eyes to look on each other more than reading kept them on our texts.

For Hlose, their love was a rapturous paradise she could never erase from her mind: The pleasures of lovers which we shared have been too sweetthey can never displease me, and can scarcely be banished from my thoughts.

But there was a downside to erotic love. Ablards work began to suffer, and his students began to complain of his absentmindedness. More occupied with composing love songs for Hlose than with making theological pronouncements, he became deaf to the rumors that rose up around them. Finally, Hloses uncle could no longer remain blind to the affair, and the lovers were obliged to separate, but not before Hlose had become pregnant. Ablard sent her away to his family in Brittany, where she remained throughout her pregnancy, while he stayed in Paris and faced her uncles wrath. The men agreed that the lovers should marry so as to repair her dishonor. No one paid any attention to Hloses objections: she would have preferred to remain Ablards mistress rather than become his wife, since she knew that matrimony would be disastrous for his career, and she shared the general view that love could not thrive within marriage.

Next page