Copyright 2020 by Wendy Moore

Cover design by Ann Kirchner

Cover images courtesy of the author; copyright Lukasz Szwaj / Shutterstock.com

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

Originally published in 2020 by Atlantic Books in the UK

First US Edition: April 2020

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Cook-Dickerman Collection is held at the Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site, National Park Service, New York State.

Pictures belonging to the Anderson family and Annie Fox are held at the London School of Economics (LSE) Womens Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moore, Wendy, 1952author.

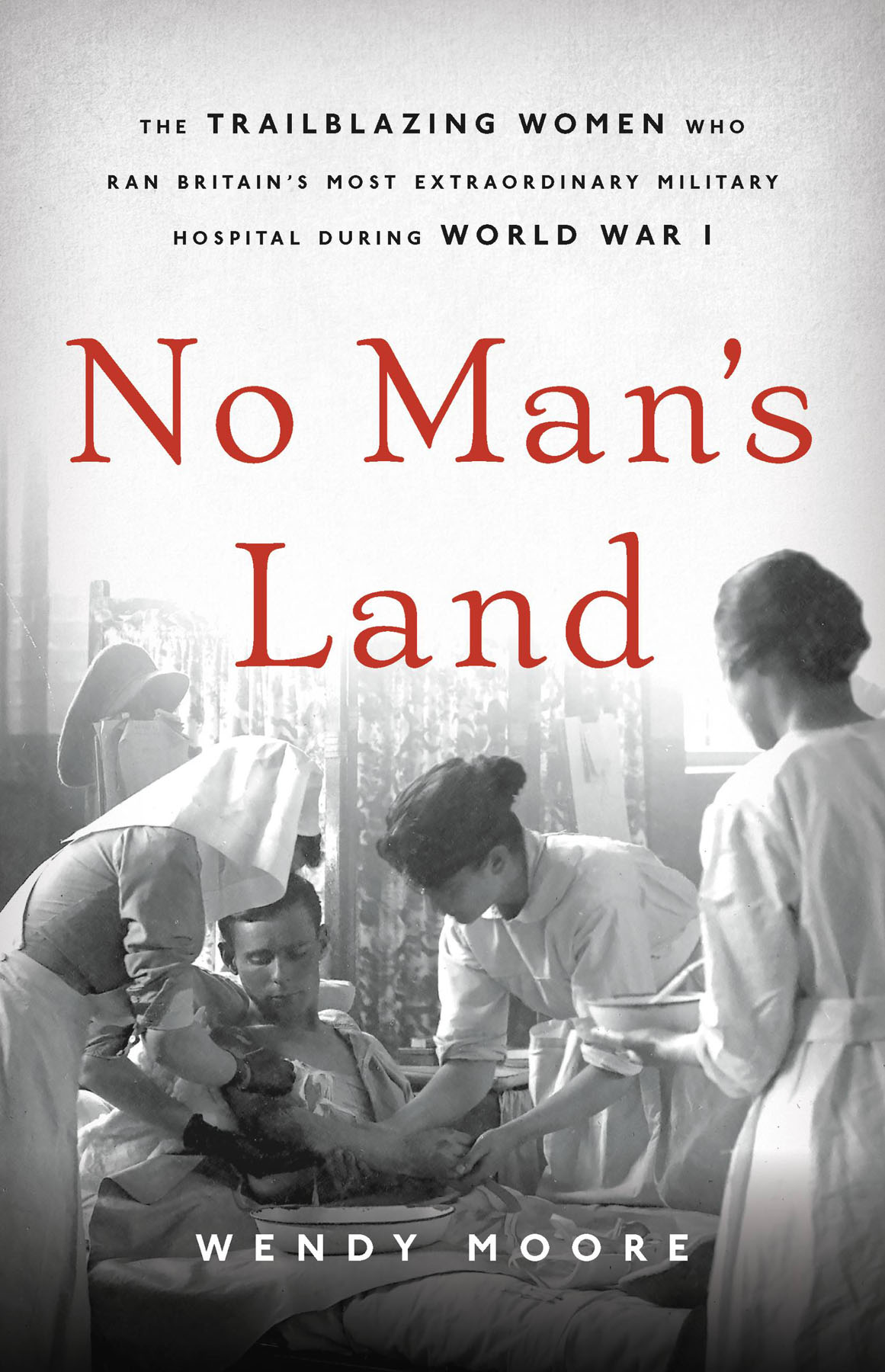

Title: No mans land : the trailblazing women who ran Britains most extraordinary military hospital during World War I / Wendy Moore.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019041778 | ISBN 9781541672727 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781541672734 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Murray, Flora. | Anderson, Louisa Garrett, 18731943. | Womens Hospital CorpsHistory. | Endell Street Military HospitalHistory. | World War, 19141918HospitalsGreat Britain. | World War, 19141918Medical careWomen. | Women in medicineGreat BritainHistory20th century. | Women surgeonsGreat BritainBiography. | SuffragistsEnglandBiography. | Covent Garden (London, England)History20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / Women

Classification: LCC D629.G7 M66 2020 | DDC 940.4/7642132dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041778

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-7272-7 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-7273-4 (ebook)

E3-20200401-JV-NF-ORI

The Knife Man: Blood, Body Snatching, and the Birth of Modern Surgery

Wedlock: The True Story of the Disastrous Marriage and Remarkable Divorce of Mary Eleanor Bowes, Countess of Strathmore

How to Create the Perfect Wife: Britains Most Ineligible Bachelor and His Enlightened Quest to Train the Ideal Mate

The Mesmerist: The Society Doctor Who Held Victorian London Spellbound

To Jennian

Guide, mentor, and friend

And for all the women who worked at Endell Street and all the men and women who were treated there

The Staff of the Military Hospital Endell St., August 1916

(BY KIND PERMISSION OF ANNIE FOX.)

Covent Garden, London, 1915

It was like slipping into a dream. Or waking from a nightmare. They had grown used to the constant thunder of shelling, the crackling of rifles and machine guns, the screams and groans of their comrades. Now all they could hear was the gentle thrum of the city at night as they rumbled through dark, deserted streets. For months, they had known only the rural landscapes of France and Flanders, where every living thing had been crushed and obliterated into the mud of the trenches and shell holes. Now they were being driven down a narrow street between tall buildings that blotted out the night sky. They had been living in a world peopled by men. But now they would enter a world run solely by women.

Most of them were young men in their twenties and thirties; some were just boys in their late teens. Officially, they were supposed to be at least nineteen to fight overseas, but some had lied about their age. Many had signed up in bands of friends in a fit of patriotic zeal, or shown up shamefaced at a recruitment office after being challenged with a white feather by a stranger in the street. For some, being injured had come as a blessinga Blighty wound that allowed them to escape the death and devastation of war. For others, their injuries meant a new kind of terror and fear for the future: the prospect of never working, perhaps never walking again, the possibility of perpetual pain, of permanent disfigurement. They had suffered long and agonizing journeys, having been scooped up from the battlefield by regimental stretcher-bearers, sometimes after lying abandoned for hours in no-mans-land before being shuttled back to casualty posts in tents and dugouts for basic first aid, a shot of morphine, and perhaps a hurried operation. They had been transported in ambulance trains to one of the French ports, crammed into hospital ships to cross the Channel, then packed into Red Cross trains bound for London. Arriving at one of the mainline stations, they had been collected by volunteers who drove them in ambulances or private cars across town. If the men asked their drivers where they were being taken the answer came: To the best hospital in London.

When they pulled up outside the old workhouse building in Endell Street, in the heart of Londons Theatreland, the great black iron gates were opened by a woman in a military-style jacket and ankle-length skirt. The ambulances juddered to a halt in the dimly lit courtyard, and women stretcher-bearers, wearing the same military-style uniforms, carried them to a lift. When they arrived on one of the wards, they saw a room bright with colored blankets and fragrant with fresh flowers. Rows of patients watched, their heads resting on crisp white pillows, as the new arrivals were lifted onto coarse blankets protecting the beds from their muddied and bloody uniforms.

The men were surrounded, naturally enough, by female nurses, orderlies, and clerks. Then the doctors arrived. And all of these were women, too. From the physician who assessed the condition of the patients to the surgeon who inspected their wounds, from the radiologist who ordered X-rays to the pathologist who took swabs, from the dentist who checked their teeth to the ophthalmologist who tested their sight, every one of the doctors was female. Other than the burly policeman at the entrance and a handful of male orderlies who were too old or too infirm for combat, the Endell Street Military Hospital was staffed entirely by women.

For some of the men who arrived at Endell Street on one of those dark nights, the stink of the trenches still clinging to their uniforms, to enter this female world after living in the hell wrought by men was a glorious relief. But for others it was a threatening, shocking, even distressing experience. Women nurses were one thing. Many of the men had already had their wounds dressed by female nurses in field hospitals and on ambulance trains. Women doctors were something else entirely. None of them had ever been treated by a female doctor in civilian lifethe idea of women providing medical care to men was simply unknownand they knew full well that women doctors were not ordinarily employed in the army. Some of the men had wounds in intimate places; others had contracted venereal diseases after sexual encounters with women in France. A few were convinced they had been sent to Endell Street to die, that they were hopeless cases. For why else would the army dispatch them to a hospital run solely by womenand not just any women, but suffragettes, former enemies of the state?