Contents

Guide

Patricia and Robert Malcolmson are social historians who have edited several diaries for publication. They have edited three different volumes of the diaries of Nella Last, the inspiration for the award-winning drama Housewife, 49: Nella Lasts Peace, Nella Last in the 1950s and the collected edition The Diaries of Nella Last. Patricia and Roberts other books include The View from the Corner Shop: The Diary of a Yorkshire Shop Assistant in Wartime (the diary of Mass Observation writer Kathleen Hey) and Women at the Ready, a history of the Womens Voluntary Services on the Home Front during the Second World War. They live in Nelson, British Columbia, Canada.

The Mass Observation Archive at the University of Sussex holds the papers of the British social research organisation Mass Observation. The papers from the original phase cover the years 1937 until the early 1950s and provide an especially rich historical resource on civilian life during the Second World War. New collections relating to everyday life in the UK in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have been added to the original collection since the Archive was established at Sussex in 1970.

Kathleen Johnstone (1913-1982) was a diarist for Mass Observation between June 1943 and September 1946.

HarperNorth

Windmill Green

Mount Street

Manchester M2 3NX

A division of

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperNorth in 2022

1 EDITION

Copyright in selection and editorial matter Patricia and Robert Malcolmson 2022

Mass Observation Material copyright The Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive

Cover design by Emma Rogers HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2022

Patricia Malcolmson and Robert Malcolmson assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008519155

Ebook Edition July 2022 ISBN: 9780008519162

Version 2022-06-28

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008519155

I like people who keep diaries: they are not as others, at least not quite

Henry Chips Channon, Diaries, 11 July 1939

Contents

How does a good diary come to exist? There must be many plausible answers to this question, some emphasizing circumstances, others the personality of the writer, others still a blend of both. Some good and now well-recognized diarists emerged virtually out of the blue. This was the case with Nella Last (b. 1889) of Barrow-in-Furness, the Housewife, 49 vividly portrayed on film by the late Victoria Wood. Nella Lasts lovingly detailed and engaging diary, which she began at the end of August 1939, runs to millions of words and four books have now been published based on what she wrote.

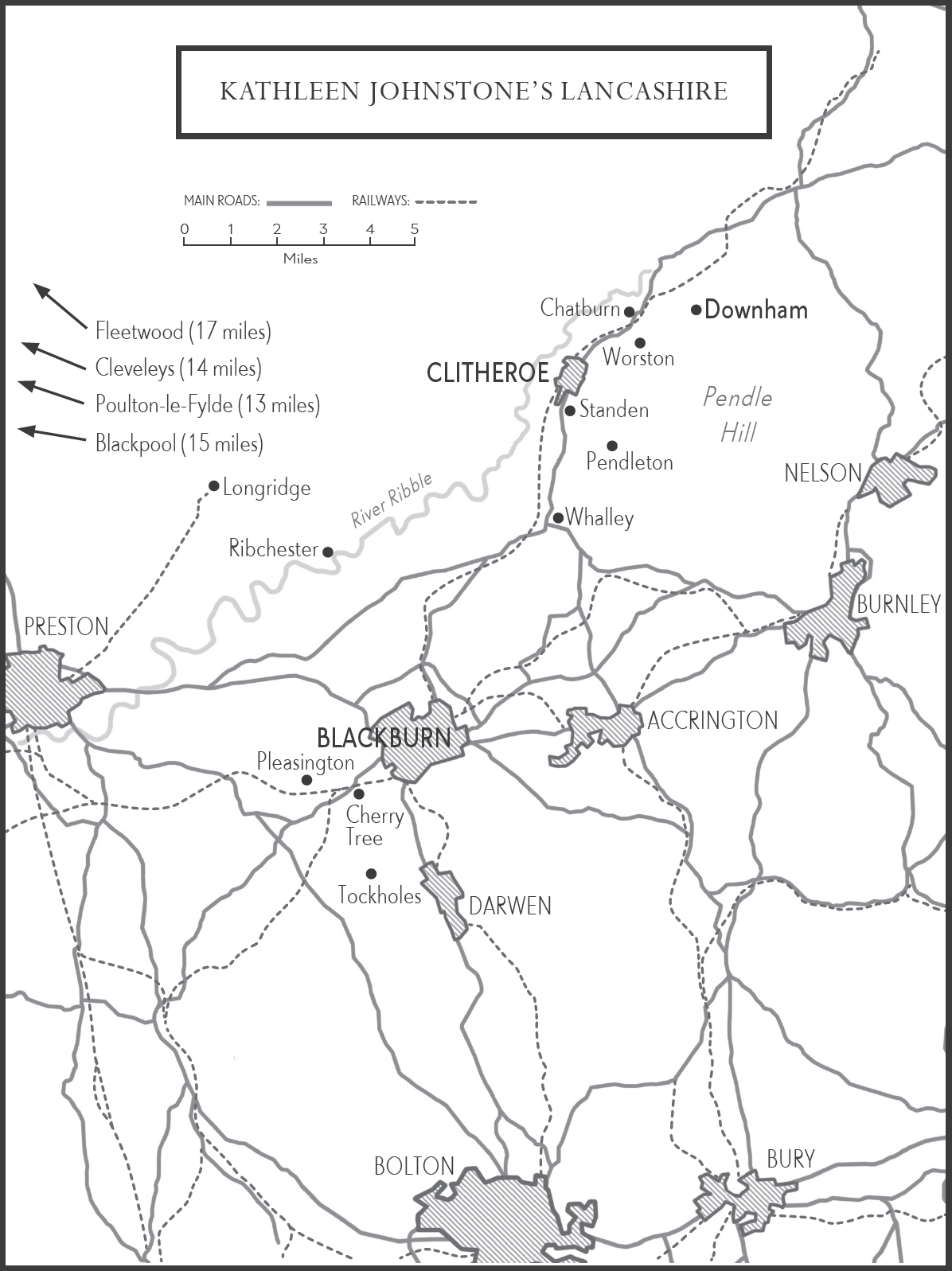

Perhaps the same sort of surprised discovery can be linked with the diary of Kathleen Johnstone, a student nurse in Blackburn, Lancashire, who began her diary in June 1943. Like Nella Last, she, too, wrote for Mass Observation (MO), the social research organization launched in 1937 to foster a sort of social anthropology of contemporary Britain. MO wanted to collect evidence on a wide range of topics, often relating to the everyday life of ordinary people that is, aspects of life that had previously not been much studied. Diaries were seen by MOs leaders as one way of capturing these social realities, in the manner that a camera might. Hundreds of people signed up as diarists. A few proved to be very good at it. Kathleen Johnstone was one of them. From the start she revealed her talents as a diarist, drawing readers into her life and times, her personal feelings and observations of public lives and events, all during the last two years of the Second World War.

Kathleen Johnstone was born on 16 November 1913 in Sharnbrook, Bedfordshire, the first child of George and Ellen Johnstone. The couple had met while they were servants at Tofte Manor, a large house in Sharnbrook. He was a footman and later a butler (when Kathleen was born), she a housemaid. They had married in 1912. The Johnstones were to have two more children, Phyllis (b. 1916) and Stanley (b. 1920). George Johnstone spent most of the First World War as a gunner in the Royal Artillery and was discharged from the Army in 1919. Once in her diary (2 September 1944), Kathleen reflected on the struggles of her mother during this war, caring for two young children and trying to get by with little money. These were undoubtedly years of hardship for the family.

George Johnstone spent most of his post-1918 adult life as a butler in households in different parts of England. For some fifteen years after the First World War, he was butler to Algernon George Lawley, 5th Baron Wenlock (18571931), at Monkhopton House, near Bridgnorth, Shropshire. The Johnstone family lived in Monkhopton; the children attended the local village school, and Ellen was a post mistress. George left this position in 1935, soon after the death of Lady Wenlock, and probably served briefly in at least two different houses during the following two years (one of them Hungerford House, near Fordingbridge, Hampshire, a country home of the Bishop of Salisbury). Then, in later 1937, George and Ellen moved to Downham, Lancashire, where he took up a position as butler to Ralph Assheton at Downham Hall. George remained in this position for the following fifteen years, including all thirty-nine months during which Kathleen wrote her diary.

Kathleens life before the 1940s is thinly documented. It is virtually certain that she lived for all or most of the 1920s with her family in Shropshire, probably leaving school in or about 1928 perhaps even earlier. Family members report that she was away from home in hospital for considerable periods of time in the 1920s, probably because of the rheumatic fever she had contracted. She is remembered by relatives as later walking with what seemed to some a limp, to others a certain stiffness of gait, and sometimes using a stick, a result of those childhood illnesses that had kept her away from school. This sickly childhood is never mentioned in her diary. Despite a disrupted education, Kathleen was a committed reader, and in adulthood many books of various kinds passed through her hands. She was interested in all sorts of topics. She spent at least some of the 1930s as a nursery governess, perhaps in London; certainly, she knew London reasonably well and had lived and worked there for an undisclosed period of time. Her other residences in the 1930s (as recorded in her sisters address book) include Bexhill in East Sussex and East Grinstead in West Sussex, and there were probably more. Family records indicate that she received a Red Cross certificate for anti-gas training in 1938.