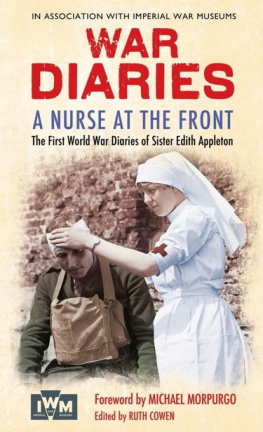

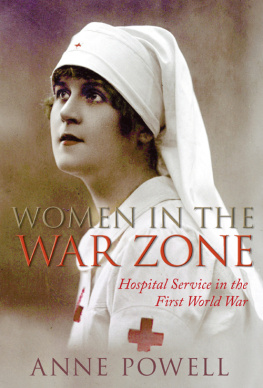

A Nurse at

the Front

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2012

A CBS COMPANY

In association with the Imperial War Museum

Text copyright Dick Robinson and Imperial War Museums 2012

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Edith Appleton and Ruth Cowen to be identified as the author and editor of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1998.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have inadvertently been overlooked, the publishers would be glad to hear from them and make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-85720-223-9

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85720-224-6

Typeset in Caslon by M Rules

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

To the dedicated women who

selflessly nursed our sick and wounded men

and

For all those silent or yet unheard voices from

almost 100 years ago

Contents

Foreword

The First World War, the horror and the pity of it, still has a tremendous hold on our collective imagination. It has compelled artists, poets, writers, ordinary and extraordinary people alike. What makes these diaries so remarkable is that, in her vivid and detailed accounts of her working experience in France, Belgium and Germany, Edie Appleton might be considered in any one of those categories.

I was of a generation perhaps the last where it was still possible to gain first hand spoken accounts of the First War. I have tackled the subject a number of times, perhaps most notably in War Horse, which I wrote in the early 1980s and which twenty-five years later has been given a whole new lease of life by the National Theatre and now has yet another life as a film. My inspiration for War Horse was fuelled directly by conversations I had with a handful of octogenarians who were living at the time in my tiny village of Iddesleigh. A few of them had gone to war with the Yeomanry and recalled vividly the close relationship that existed between horse and trooper. Part of the impulse for me in turning their memories into fiction was in tribute to them: my own way of passing their experiences on. Reading these extraordinary diaries of Edie Appleton, I have something of the same feeling I had then, sitting among those brave men a feeling of extraordinary privilege to be listening to such stories at first hand.

In the following pages, whether she is dealing with the daily horrors and atrocities that faced her as a nursing sister, or the joys she was able to snatch for herself, away from the devastation and carnage, Edie is frank and straightforward. The authenticity of her voice and of what she writes about is something that cannot be replicated. Her vivid recall of detail is meticulous and yet nothing is superfluous: a bomb that lands so close to the hospital and makes the air so thick with red dust... that we could not see out of our windows. Her own emotions are kept movingly in check, but not out of view: we tried to become used to the five-minutely explosions of big shells close to us, but it was difficult and my knees did shake.

There are heart-breaking moments, like her insistence on giving the dying and wounded soldiers a clean handkerchief. She says, I dont know why, but they love to have it. One soldier tells her that she is like a mother to him and we can clearly see why: it is in just such small, thoughtful gestures like a mother sending a child off to school with a straightened jacket, combed hair, clean handkerchief that we see her great skill and tact in caring and comforting.

What shines through is her good humour, her determination to get on with the job, to make the best of circumstances. And this includes finding moments of sanity in which to appreciate the countryside a rest in a beautiful wood just outside Hazebrouck, with a picnic tea, or swimming in the sea on a sultry morning, the sea absolutely clear with waves smooth-topped and lumpy; or, even, luxuriating in the bathrooms and bedrooms of what had once been a posh seaside hotel, turned into a makeshift hospital.

She shows us the reality of dealing with horrors, the overwork and the undersleep, which inevitably sometimes leads to hysteria. One poor sister, who is confronted by a mortuary corporals dismay at not being able to differentiate dead officers from the other ranks, because, (unbelievably) he explains, it made a difference how they were each to be buried: Men is ammered officers is screwed. The sister, Edie tells us, went hysterical and laughed and laughed. The more she told herself it was tragic and not funny, the funnier it all looked.

There are any number of such insightful observations on any page you care to choose. What is remarkable is that in the midst of the most appalling conditions, Edie had the presence of mind, the strength and the courage, to record these things for herself. It is a further miracle that these diaries have survived and, thanks in large part to the care and generosity of her relations, that we find ourselves in the privileged position to be able to re-live her experiences for ourselves in our own time.

Michael Morpurgo

Introduction

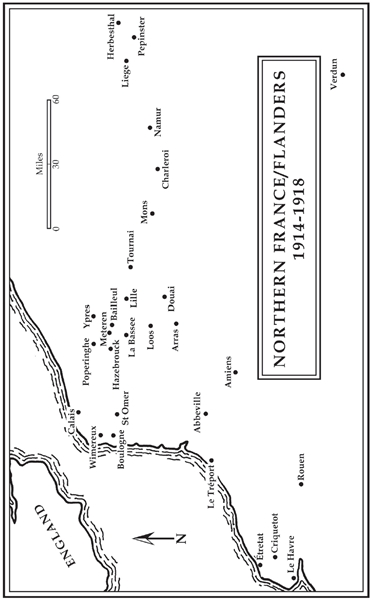

The Great War diaries of Edith Appleton paint an exceptionally vivid picture of daily life just behind the lines, in the makeshift clearing stations and hospitals which received wounded and dying men straight from the Front. Simultaneously, they chart the transformation of the northern French towns, villages and landscapes which the conflict irrevocably changed over the course of those four bloodstained years.

Edith (known as Edie or E) served in France and Belgium throughout the war. Following the Armistice, she continued to work first on an ambulance train, transporting casualties and repatriating prisoners of war, and then on the staff of the Matron-in-Chief in Boulogne, until her demobilisation in December 1919. A conscientious diarist, it is likely that she wrote her detailed and engaging journals right through from her enrolment as a military nurse in 1914 until her permanent return home. She seemed to manage to create for herself a brief pause in which to chronicle the events going on around her during even the busiest times at the height of great battles. However, the first volume we have begins in April 1915 (frustratingly, on a page numbered 112), almost seven months after her departure from England. There are other missing sections as well, most significantly an entire journal charting her life between November 1916 and June 1918.

Despite this long gap, the 400 mainly handwritten pages of Edies diaries make a valuable and moving contribution to the literature of the Great War. For Edie was not just an intelligent observer, but a compassionate and nuanced writer, with a gift for thumbnail characterisation, a quick wit and a sharp eye for the telling detail. Acutely aware of the significance of the events she witnessed from the sidelines the first gas attacks, the ebb and flow of casualties as the great battles waxed and waned she never deviates from a frank and competent account of what she witnessed. The horrific wounds, the amputations, the seemingly endless procession of agonising deaths. She calmly reports the effects of gas and shellshock neither of which had been seen before and the extreme youth of most of those who died. Nothing is spared, nothing is embroidered and Edie never takes refuge in sentiment. Indeed her unflinching account is perhaps especially surprising as the diaries were addressed to her mother Eliza, whom Edie might have been expected to protect from the most graphic details.