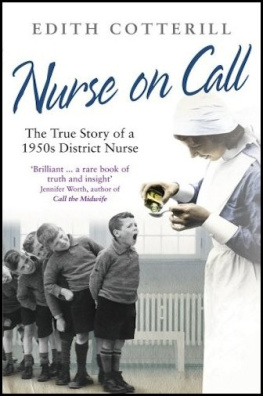

Nurse on Call

The True Story of a 1950s

District Nurse

Edith Cotterill

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781409003335

www.randomhouse.co.uk

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in 1986 by Century Hutchinson Ltd This edition published 2010 by Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing A Random House Group company

Copyright Edith Cotterill 1986

Edith Cotterill has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

ISBN 9780091937560

To buy books by your favourite authors and register for offers visit www.rbooks.co.uk

Contents

In memory of Judith and Elizabeth

1

Refresher Course

I WAS A district nurse of long standing. I have the feet to prove it, and for many years I plodded a Blackcountry beat. Patients can be a pleasure or a thorn in the flesh, but if you attend them long enough you become fond of them.

Mrs Tibbs was one of the thorns. She was a randy old warhorse squabbling with all and sundry and thriving on the belligerency, but there was a bond between us which was a combination of affection and armed neutrality. Despite being very handicapped she lived alone, and if she had any relatives they had long since learned to keep their distance. When the Meals on Wheels service got into full swing it seemed just what she needed and I persuaded her to try it out.

The wheels were represented by a converted van chauffeured by a military-type retired gentleman, and the meals were produced by a brisk lady in green. Whenever I saw them they looked piping hot and delicious, but Mrs Tibbs yammered peevishly, I cor ate it, Its riffy! or The taters aye dun.

She speculated evilly on what went on between the military gent and the lady in green. The strumpet! An es nowt but a bloody ponce!

In vain I defended them, threatened her with slander or simply turned a deaf ear.

No good tellin yo nuthin, she grieved. An me a poor widder woman wi me fittle arf cooked. No wonder me ballys all of a wamble.

One day I arrived to be confronted with a pea on a saucer.

Theer! Mrs Tibbs indicated it triumphantly. I bet yo cor ate that!

Tentatively I squeezed the pea between thumb and forefinger and agreed; it was as hard as a bibble. But she was not to be put off with that.

Goo on! she bellucked. Yo try bitin on it!

Gingerly I bit hard on the offending pea which immediately shot across the room.

Theer! she rejoiced hugging herself. Yo cor ate it neither, an whats more its bin threw me once.

When Dr Quinn arrived green from Ireland and with a brogue that could be cut with a knife, it caused much consternation amongst the patients he had inherited. The fule, they chuntered. E cor even spake praper. Es bloody daft!

He in turn suffered frustration. Oill niver understand them, he mourned. Theyre for iver tellin me theyve not been to the ground. What in hells name dya make o that?

Loyal to the locals, I expressed surprise that he, a medical man, did not recognize such a common term for constipation.

Holy Mither o God! he keened. Youre but another of em, an heres me thinkin all nurses are Oirish!

In an effort to make themselves better understood, patients bawled at the top of their voices; symptoms and sufferings were shouted aloud and the surgery waiting room became a place of entertainment. Hitherto secret ailments were disclosed to all and sundry. These were compensations indeed!

Mr Wagstaff was a patient of Dr Quinns and Mr Wagstaff had pneumonia. He had got it specifically to annoy Mrs Wagstaff, for she resented having strangers traipsing about her immaculate house. In particular, she abhorred Dr Quinn, whose feet were very large and whose boots were always muddy. Poor man! He had no wife to clean them.

Nurses she regarded with suspicion as being no better than they should be. After all, when you thought of the things they did to folks! No self-respecting woman would be a nurse.

Mrs Wagstaffs mother and sister, replicas of herself, were part of the household and the three martinets darted about before me strewing newspapers where I might tread. Arter all, reflected the old mother sotto voce, yo doh know where ers bin! Poor Mr Wagstaff. My heart went out to him.

In my earlier days pneumonia patients had a lysis and a crisis. They were propped up in Fowlers position and their labouring chests suffered the added burden of kaolin poultices. In recent years antibiotics have taken over, and a course of intramuscular injections, dexterously aimed at the tenderest part of the posterior, usually gets the sufferers on their feet in a week. (No doubt propelled there by their tortured buttocks!) Mr Wagstaff was the exception to the rule: he did not respond to treatment and his malaise dragged on. Neighbours talked darkly of the insurance policies with which he had been backed.

One morning my visit coincided with that of Dr Quinn. I groaned inwardly and edged for the door, but anticipating my escape, he took my arm and drew me outside onto the landing, followed by the relatives with ears cocked and eyes agog.

Oill consult with nurse alone, please, he said, and motioning me into the adjoining bathroom, closed the door on their frustrated faces.

Mrs Wagstaffs bathroom was as prim as herself and camouflaged with much candlewick. A prissy pink cover did its best to disguise the lavatory seat, and on this the young medico perched himself with a cigarette while I sat angled on the edge of the bath. Concern increased within me; however would I make up for lost time?

Having secured a captive audience, Dr Quinn waxed eloquent, oblivious to the fact that half the time I could not follow his jargon anyway. Outside, creaking floorboards reminded us of the waiting relatives. When his second cigarette had gone up in smoke, Dr Quinn finally prised himself off his perch on the pedestal and automatically, before I could stop him, pulled the dangling chain.

As the water flushed noisesomely we stared at each other in horror. Outside, a stony silence condemned us. There was only one way out through the door. Sheepishly, we took it.