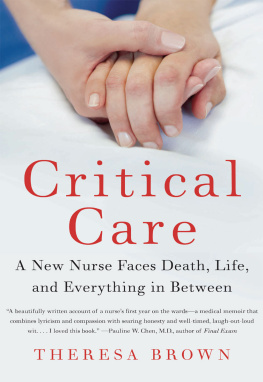

THE SHIFT

One Nurse, Twelve Hours, Four Patients Lives

THERESA BROWN

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2015

To Sophia, Miranda, and Conrad

the beginning of this journey

If all is supposition, if ending is air, then

why not happiness? Are we so cynical,

so sophisticated as to write off even the

chance of happy endings?

TIM OBRIEN

In the Lake of the Woods

So we come down from stony haunts

the hypothetical eternalto find another

way into the garden...

this time well pick the other Tree

and eat the fruit of life.

ELEANOR WILNER

Sarahs Choice

Disclaimer: This book is a work of nonfiction and the stories told here are true, drawn from my time spent working as a bedside nurse on a bone-marrow transplant/medical oncology floor in a teaching hospital in Pennsylvania. Specific details have been changed to conceal the identities of patients and coworkers, and in the interest of protecting patient and staff confidentiality some characters are composites. Conversations and events in The Shift are reproduced to the best of my memory, though I have altered some short exchanges for clarity. The real patient behind the character of Ray Mason in The Shift gave me permission to tell his story here. HIPAA requirements make it potentially illegal for hospital nurses to track patients down after theyve been discharged from the hospital and I did not attempt that for the other patients in this book. To avoid casting aspersions on a particular practice group I made up the incident where a procedure is done only because a patient requests it. Similar events have happened in the hospital, though. Finally, this book is not a medical textbook and should not be used as such: highly individual cases are discussed and are not necessarily suggestive of disease or treatment effects in the aggregate. All errors are my own.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

A Clean, Well-Lighted Place

The buzz of the alarm surprises me, as it always does. Six a.m. comes too soon. Ive been off for a few days and never go to bed early enough before a first shift back. Thats the problem with being a night owl at heart.

I lie in bed and think, What if I just dont go in today at all? I consider it, then realize how much the nurses I work with would hate me if I didnt show up.

I close my eyes one last time, though. It feels good to float in the warm darkness, Arthur, my husband, asleep next to me. There wont be any floating once I hit the hospital floor. Ill have drugs to deliver, intravenous lines to tend, symptoms to assess, patients in need of comfort, doctors who will be interested in what I have to say and others who wont, and my fellow RNs, who with a combination of snark, humor, technical skill, and clinical smarts, work, like me, to put our shoulders to the rock that is modern health care and every day push it up the hill.

The memory of that effort comes back to me, keeping me in bed, but theres something else, too, some feeling I dont want to own up to. Its why Im hiding under the covers: Im afraid. Afraid of that moment when the rock slips and all hell breaks loose.

For me it was the patient who started coughing up blood and within five minutes was dead, just like that. Ive told the story many times, written about it, thought about it. Seven years later it has gotten easier. But remembering it I feel a flutter in my stomach, a tightening of my jaw.

That day the rock wrenched itself free, and until then I hadnt fully understood that we could completely lose control of a body in our care. It wasnt for lack of exertion; it was destiny, or fate if you prefer, that tore the rock away from me. I had run after it hard and fast, doing CPR in scrubs splattered with blood and calling in the code teamthose professionals, usually from the ICU, trained for rapid responses, who try to rescue patients when they crash. The nurses and doctors did their best for this patient, but they couldnt save her, and in the end a person whod been alive and talking and laughing was living no more.

I put that memory away, get out of bed. Its early November and dark out and I prepare for Pittsburghs late-autumn weather by pulling on riding tights and my wool sweater that proclaims Ride Like a Girl. The sweater makes me feel young.

Brushing my hair, I almost forget to put on my necklacea small silver heart charm surrounded by the words I and Y-O-U. The heart has the tiniest of rubies stuck in the center, so that when it catches the light it seems to glow with life, like a human heart. Arthur gave me the necklace for our anniversary a few years back. I reach behind my neck with both hands and secure the clasp, comforted by having a reminder of love in the hospital.

As I move down the stairs, the house is hushed. Arthur remains asleep, as do our three children. I think about the sleeping kids, and a smile crosses my face: our son is fourteen, our twin daughters, eleven, all with variations on their dads curly hair, the girls blond, as I used to be, too. None of them will get up for school until long after Im gone. The dog doesnt even wake up with me in the morning, but the truth is, I like it quiet like this. The warm blue of our cabinets and our pot rack in front of the kitchen window make me happy. In the silence of the morning I take a mental snapshot of the kitchen as a dose of home. Home is a vaccine against the stresses of nursing.

Oh, food! I pick up a banana from our fruit bowl, peel it fast, and then eat it while drinking a glass of water. I should scramble eggs, toast bread, or even pour a bowl of cereal, but I dont get up early enough to do any of that, and anyway Im not hungry first thing in the morning. My mother tells me my eating habits around work are unhealthy. Uh-huh. Shes right, and the irony is not lost on me, but the shift starts at 7:00 a.m. and Im never hungry until 9:00. I cant change that.

Lunch? I grab a yogurt, an apple, slap together a turkey sandwich, light on the mayo, and stow it all in my bike bag. The cafeteria food all tastes the same to me so I try not to buy my lunch. I see my reflection in the glass sliding door. Dont have my game face on yet: my blue eyes look wary, waiting. The house remains silent as I sit on the stairs and tie my biking shoes. Then I put my bright yellow Gore-Tex jacket on, wrap my neck for warmth, and slide my bag over my shoulder.

I head down into what a friend calls our Norman Bates basement. Its where I keep my bike. Theres no dead mother down here preserved with taxidermy, although you could find more than a few cobwebs and the sparse lighting makes the corners impenetrable. As a child I was terrified of the basement in our house and my best friend loved to tell stories about horrors befalling innocent young girls in creepy basements. I wonder why I listened to her. I must have enjoyed the thrill, that frisson of fear that came from transforming our very ordinary cellar into a place of the macabre.

My bike is stacked up against our familys four other bikes. The basement is limbo, a portal between the ordinary joys and struggles of home and the high-stakes world of the hospital. I put on my helmet and lock the basement door behind me as I leave, awkwardly carrying my bike out the low door and up the few steps. As usual, Im running late. I turn on my bike lights, saddle up, and push off.

Its two miles to the hospital and the ride starts with a downhill. I enjoy the feeling of moving without work, having the world shoot past as I pick up speed, my front light illuminating a slim strip of road. I barely brake at the first stop sign, making a quick left down an even steeper hill that makes me go even faster. The rush is fun.