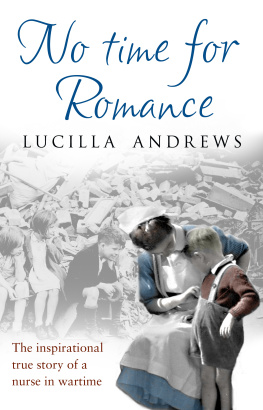

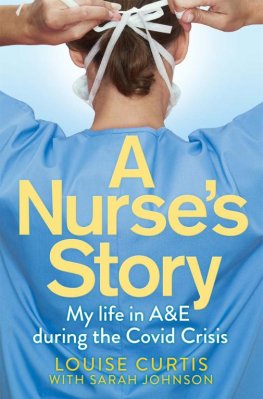

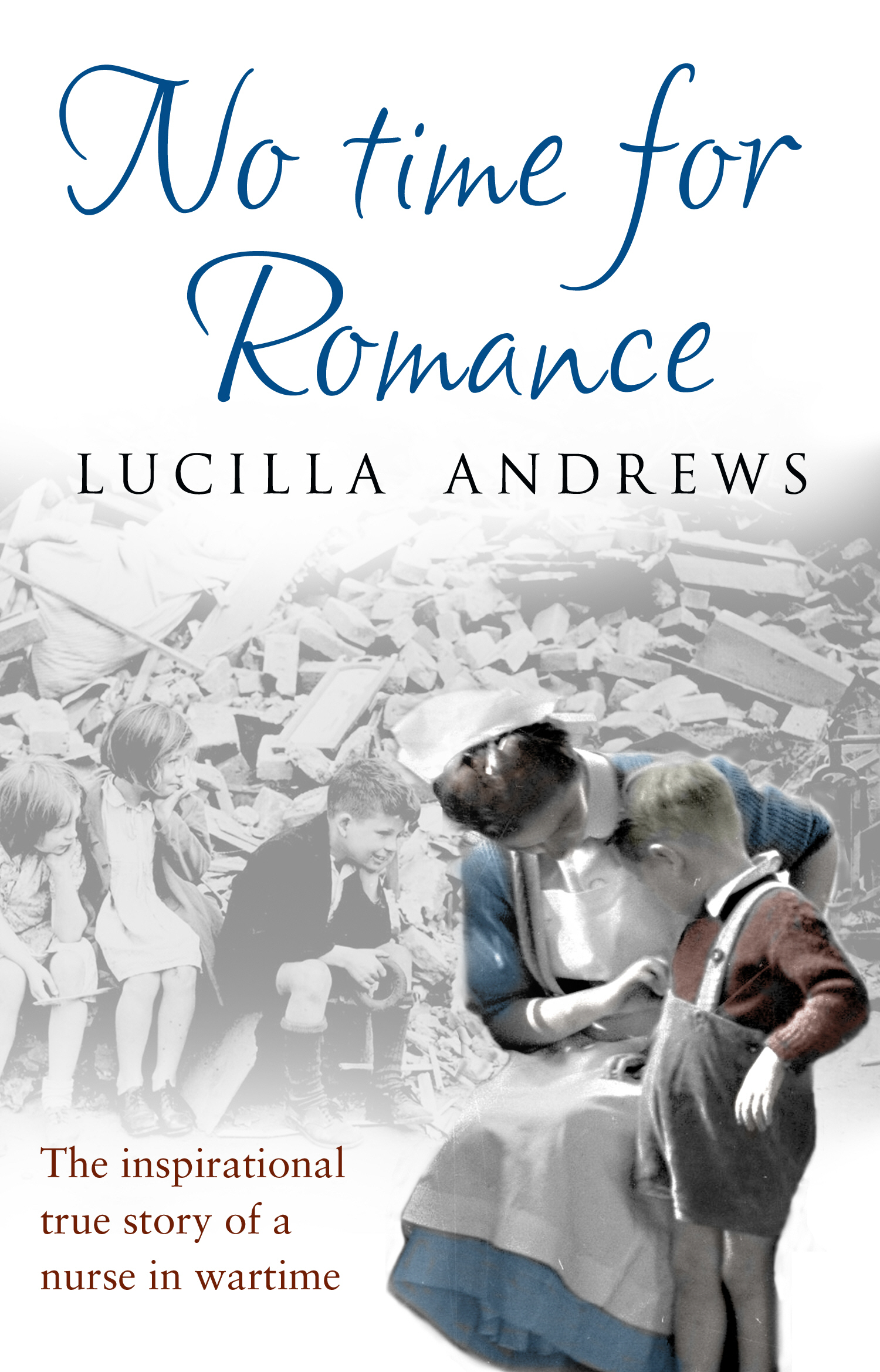

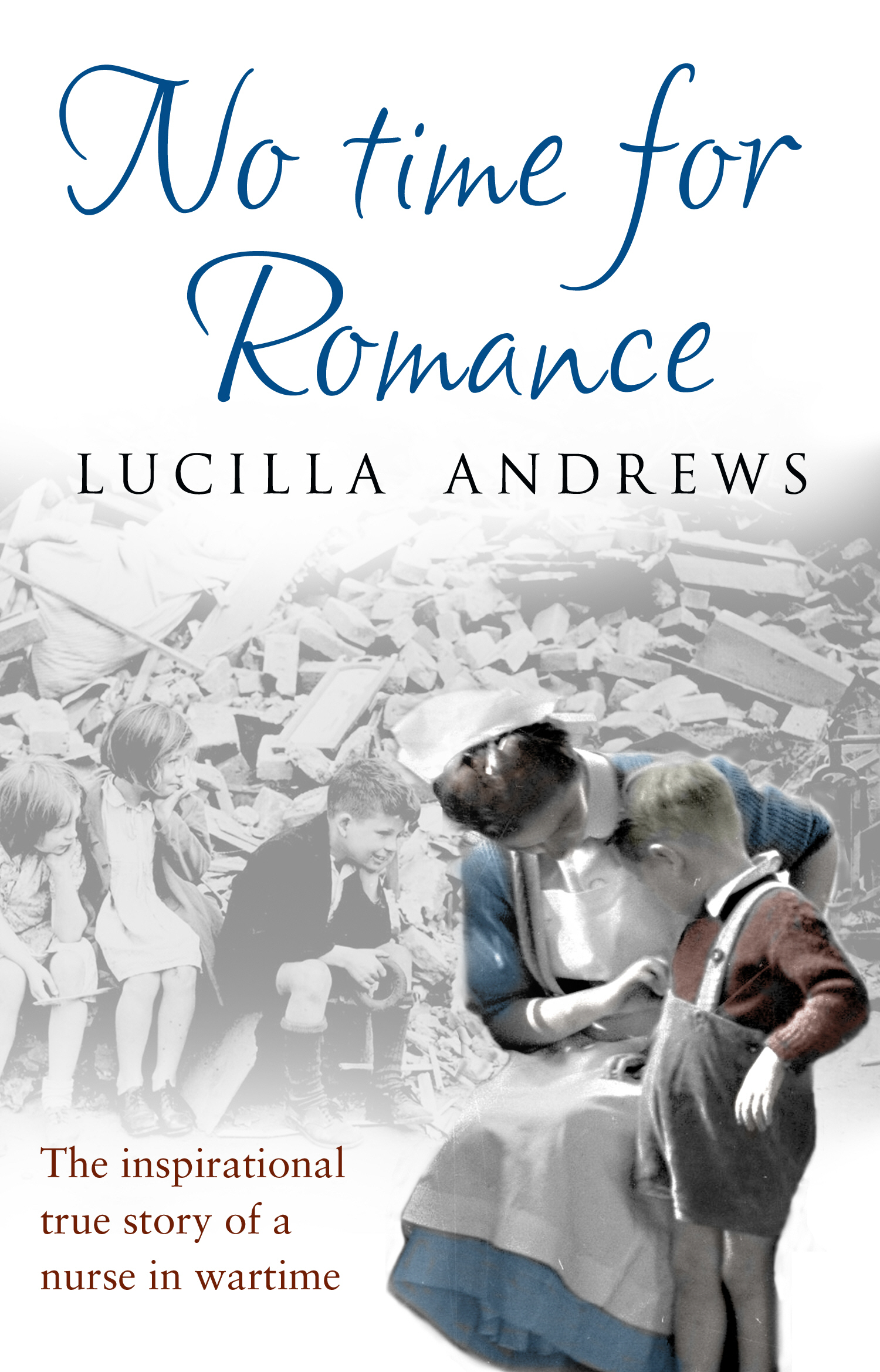

About the Book

Lucilla Andrews was only eighteen when, as a volunteer nurse at the beginning of the Second World War, she experienced the grim realities of wartime. Young, inexperienced and coming from a comfortable and sheltered background, she found herself dealing with survivors from Dunkirk and the victims of the Blitz. Seeing these horrors at first hand had a profound and lasting effect upon her, and made her determined to train as a nurse at St Thomass Hospital.

No Time For Romance is her story, the powerful and moving account of a young girl in wartime London, learning the hard way about medicine, injuries and death, as well as love and hope. It is a story both of personal courage and of the courage of the British people at war.

NO TIME

FOR ROMANCE

Lucilla Andrews

Contents

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

6163 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

A Random House Group Company

www.transworldbooks.co.uk

NO TIME FOR ROMANCE

A CORGI BOOK : 9780552164818

Version 1.0 Epub ISBN 9781446488164

First published in Great Britain

in 1997 by Harrap & Co. Ltd

Corgi edition published 1978

Corgi edition reissued 1988

Corgi edition reissued 2007

Corgi edition reissued 2010

Copyright Lucilla Andrews 1977

Picture acknowledgements The photos come from the original paperback edition of No Time For Romance except for the following: Flying bombs [by radio from Stockholm and HU 6326] and damage to St Thomass, 1940, [Albert Ward 70378, view through doorway 85054]: all Imperial War Museum; view of damage and Big Ben, 9 September 1940: Getty Images. St Thomass hospital interiors: all Imperial War Museum; little boy in hospital, 1940: Getty Images. Temporary St Thomass, Godalming and St Thomas's terrace: both Getty Images; VE Day celebrations: both Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis.

Lucilla Andrews has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some limited cases names of people, places, dates, sequences or the detail of events have been changed solely to protect the privacy of others. The author has stated to the publishers that, except in such minor respects not affecting the substantial accuracy of the work, the contents of this book are true.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Addresses for Random House Group Ltd companies outside the UK can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk The Random House Group Ltd Reg. No. 954009

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

To all my fellow-nurses, trained and untrained,

who worked in all British hospitals,

at home or overseas, in the

Second World War

About the Author

Lucilla Andrews was born in Suez, the daughter of an English father and a Spanish mother. She went to school in England and wrote her first (unpublished) novel at the age of eleven. During the Second World War she trained as a nurse at St Thomass Hospital in London.

Lucilla Andrews later became one of Britains leading romantic novelists, and many of her books draw upon her own experiences of her medical background. Lucilla Andrews lived in Edinburgh during the later part of her life, and she died there in 2006, aged 86. No Time For Romance is her vivid real-life account of her wartime nursing experiences.

The reader will not credit that such things could be but I was there and I saw it.

IZAAK WALTON , 15931683

Chapter One

As always, it was the sudden silence that woke me, but that morning in March 1945, for the last time. The silence meant the flying bomb overhead had switched off its engine and within seconds would explode on the ground. By my counting, eight seconds; others varied this from five to fifteen.

I was sleeping face downwards with a then habitual pillow over the back of my head and neck. I preferred to risk a severed spine to having my face sliced off and had nursed enough flying bomb casualties to know I could have that choice. I was sleeping in my own room on the top and fifth floor of Riddle House, which was the nurses home on the Thames-side site of St Thomass Hospital, London SE1. The two others, the Nightingale Home and Gassiot House, had been destroyed by enemy action years earlier in the Second World War. By that early morning in March the air attacks were tapering to their end. Our authorities no longer insisted nurses slept in the basement shelters as they had done during the blitzes and when the flying bomb attacks had started in June 1944. For the first few weeks of the attack, between 100 and 150 flying bombs were launched on London daily. Familiarity and fatigue had bred in me not contempt but a passion for privacy. Five years wartime nursing had removed the terror from the thought of facing possible death alone. Death, as I had too often observed, seemed an inexorably lonely yet strangely unfrightening place. I remained terrified by the thought of the mutilating injuries that did not always kill.

It was that thought that triggered the conditioned reflex that jolted my body from the bed and my voice into counting aloud before my eyes were properly open. Counting, I ran from my room along the top floor and down the stairs round the liftwell. That the lift was elsewhere and out-of-bounds from 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. was immaterial as it was the last sanctuary I would have chosen in a building at risk of caving in. I reached the third landing at eight, and had just flung myself face down on the floor with both arms folded over the back of my head, when the explosion rattled teeth, bones, eardrums and every inch of metal in the liftwell. Riddle House swayed perceptibly then settled, unharmed. It was the only building I was ever in during air attacks to give that odd, reassuring sensation of riding with the punch. All the others had shaken, rocked, groaned, creaked, cracked, spattered glass, bricks, plaster, dust, and the omnipresent blackout screens. I was not in Riddle House during the London Blitz, but whenever I was in the building during the flying bomb and rocket attacks, I noticed that all it did was shed a few blackout screens and clouds of dust. If any plaster came down, it was not on my head.

I picked myself off the floor, sat on the stairs to get my breath and only then realized one of my set of fourth-year student nurses was sitting a few steps up. We looked at each other and grinned euphorically, triumphantly, because we were still alive. At few moments is life more worth living than in those following the one that could have been ones last.

My friend, as myself, was barefoot, but in short-sleeved cotton pyjamas instead of a nightie, with a navy nurses uniform cloak slung over one shoulder, and, clutched in her hands, a lipstick and her fiancs photograph. Over my cotton nightie was the small fur carriage rug I used on my bed. On the landing floor were my eyelash curlers and the much-mended-with-sticking-plaster red cardboard foolscap file of notes for the books I one day intended to write. I had no recollection of grabbing rug, curlers or notes on my way out; my conditioned reflexes had had good practice.

Next page