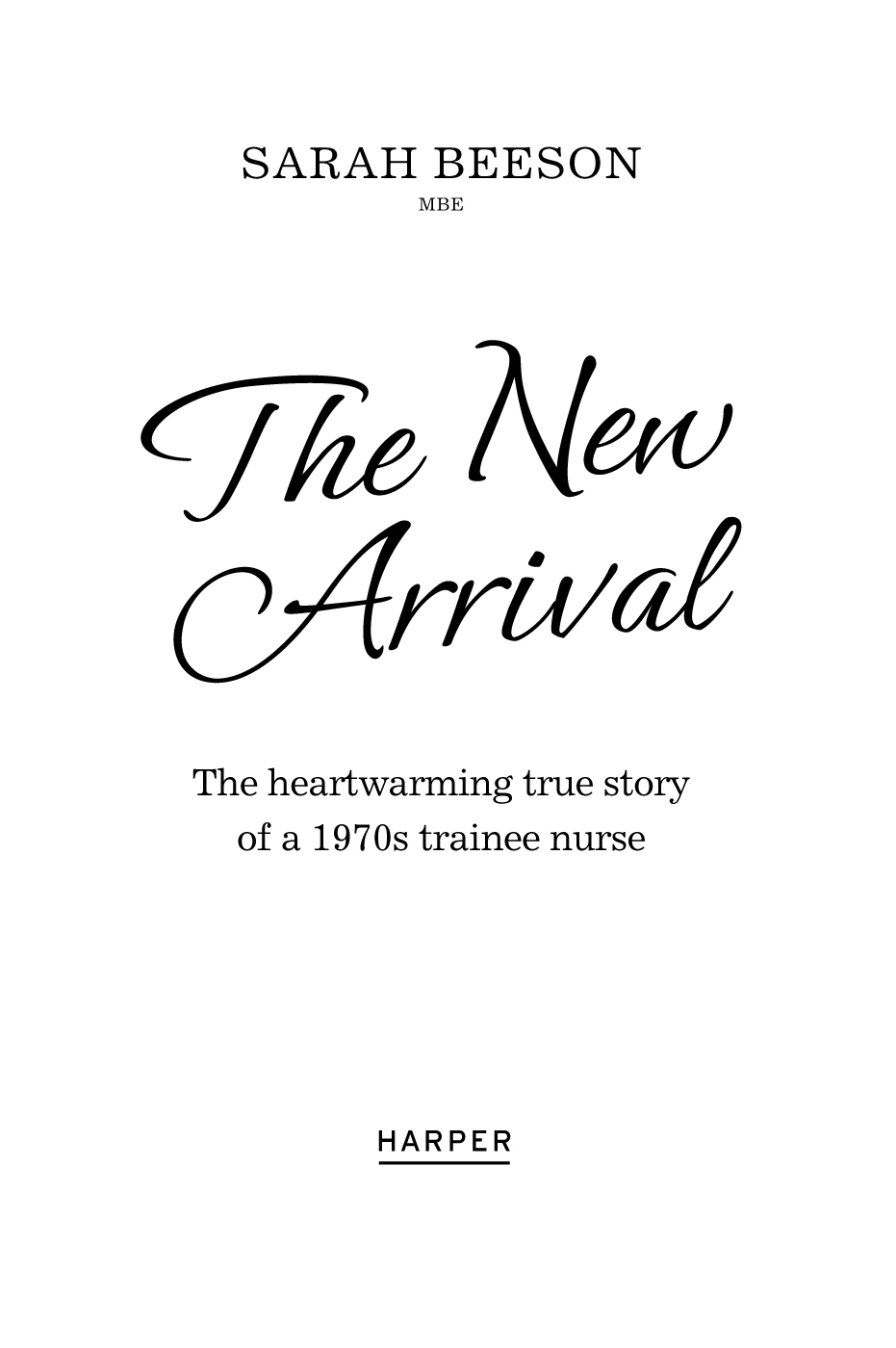

Contents

Thank you to our literary agent Piers Blofeld, who first suggested writing this story, before it had even occurred to us, and to Paul Magrs for his advice and encouragement. To Charlotte Cole for her speedy copy-editing and practical advice, and to Carole Tonkinson and Anna Valentine at HarperCollins for their alacrity. To Hannah MacDonald for seeing the potential, and Elen Jones for her enthusiasm. To Katie Ormerod at St Bartholomews Hospital Archives for the illuminating Hackney Hospital records. To John Scanlon, Hotel Manager at the Dorchester, for going out of his way to get us a 1970s menu from the hotel. To Peggy Johnson, Carmel Glennie (ne Ryan) and Dr Hugh Glennie for being part of it and for their continued friendship. To William, Jane, Bridget and Stephen Hill and Eric and Margaret Hill for being exemplary parents. And most of all thank you to Takbir Uddin and Ava.

Sarah Beeson (ne Hill) and Amy Beeson

In 1969 17-year-old Sarah Beeson then Sarah Hill arrived in Hackney in the East End of London to begin her nursing career. Six years later she went into health visiting, practising for over 35 years in Kent and Staffordshire, building up a lifetimes expertise and stories through working with babies and families.

In 1998 Sarah received the Queens Institute for Nursing Award. In 2006 she was awarded an MBE for Services to Children and Families by Queen Elizabeth II.

She later married and became Sarah Beeson. Now she divides her time between Staffordshire and London.

It was 23 September 1969, already past nine oclock in the morning. I was still sitting alone on the back seat of my fathers blue Rover P4, waiting for my mother to emerge from the house. I impatiently kicked my white round-toed calf-length Mary Quant boots against the front passenger seat. After years of practice I could do this without scuffing either the seat or my well-worn but perfectly presentable boots. All the time I kept my eyes fixed on the open front door of Uplands, our gentlemans country residence I was leaving as soon as my mother deigned to join me. Typical, I muttered under my breath. I took my last long sniff of sea air and slowly counted to ten. My ears pricked at the distinct click of my mothers court shoes on the parquet floor; she was finally making her way down the hall and outside. Two steps behind her was Harold, my fathers driver, carrying my battered old school trunk with the initials SH fading on the side. I watched icily as Mum unnecessarily oversaw Harold loading my trunk into the boot of the car before he opened her door and she slipped effortlessly onto the seat next to me. Neither of us said anything; we both sat straight backed with our knees together on either side of the back seat my mothers handbag resting perfectly upright between us. Harold took up his place at the wheel and I felt my heart skip with excitement as he started the engine and we finally made our way down the quarter-of-a-mile driveway.

I watched idly through the window as we sped down the narrow country lanes to meet the seashore and the grey little town below. Llanelli whizzed past me, stonewashed modest houses, mothers pushing carriage-like prams, small vans delivering to butchers and greengrocers. It seemed such a small, small world. Too small for my mother. She sat day by day in the big house waiting for my father to return one of the bosses at Thyssens, he arrived home almost every night of the week with at least two dinner guests expecting to be served a three-course meal. Mum rarely complained. Also at the table, merrily sitting alongside Dads international business associates, were my older brother and sister, William and Jane, the younger two, Bridget and Stephen, and often our school chums. Both children and adults consumed vast amounts of prawn cocktail and pink champagne off the custom-made boardroom-sized dining table. Dad would say to our dinner guests, Youve got to be quick in this house, as his gaggle of children lapped up our grub whether it was a curry, a Chinese or a roast.

This place was too small for me too; it wasnt my home, just the latest stop after a childhood of constantly moving to new towns and villages. Dad was a top civil engineer and we moved with him; so one year he would be working on the Dartford Tunnel and we were living it up in Sevenoaks. Next wed moved into a house custom built by my dad, on the hilltop overlooking Loch Etive, while he built the new hydroelectric plant to supply electricity for the west coast of Scotland. I wouldnt miss this house; Scotland had been the beloved place of my childhood it was there I made the transition from little girl to brooding teenager. Today, my only pang of regret was as the car went past the Chinese takeaway belonging to my best friend Sues family. Of course the shutters were down at that time of the morning, but still I looked for her heart-shaped face in the upstairs window. She wasnt there.

Mum folded her hands, her long fingers cocooned in spotless white gloves which rested lightly in her lap. I peeked up at her and drank in her portrait. Her slender frame and long neck were enhanced by a cream polo-neck jumper, complete with matching coat and pillbox hat. Her hair was still naturally dark, though she was over fifty, and swept up into a glossy brown bun on the back of her head. She was perfectly made up with just a dash of powder on her pretty tanned nose, a sweep of grey shadow on her sparkly eyes and a smear of pink lipstick on her mouth just right for this time of the morning. Beside her I was a pale-skinned dwarf. When standing, she towered a good eight inches above me, more in heels, which she usually wore. Apart from my obvious lack of height compared to the rest of my family, I took more after Dad on the inside too. Put together my brothers William and Stephen were like a pair of giant bookends. My sisters Jane and Bridget were tall and graceful like Mum. But though we all got into our fair share of scrapes, I was always the one to unintentionally rile my mother or be in hot water with the nuns at boarding school, as I shared my fathers sense of fun, sometimes at the expense of what we ought to have been doing. I wished it was just me and him driving to London on one of our rare drives together.

I heard Mum sigh as Harold deviated from the main road down yet another narrow country lane one of his so-called shortcuts that doubled the length of the journey. We wont be there till sunset at this rate, she hissed.

It was the second thing shed said to me all morning, the first being, Is that what youre wearing? Id come down to breakfast in my red suede miniskirt and black polo-neck top. I was eager to be off and already wearing my three-quarter-length navy Reefer jacket with the brass buttons, my hair still wet and falling unfettered and uncut to my chest. I considered it a rhetorical question, and moodily helped myself to the toast, jam and a cup of tea which were all ready and waiting on the breakfast table.

Now the silence was broken Mum settled upon a topic for the journey her incredulity at both my choice of career and location. All the money your fathers spent on your education. You wont last two weeks.

I didnt say anything in reply. I leaned forward and asked Harold if we could have the radio on. He tuned in to Radio One just for me. Mum huffed and opened up her square white leather handbag and to my relief took out her knitting. I was glad to hear the friendly familiar voice of Tony Blackburn on the car radio as he introduced The Archies, and soon the sound of Sugar, Sugar filled the highly polished Rover.

But my mother had made her point and I couldnt help but think back to my last year at school my secret study in the library. I kept going back and reading up on nursing. I had been pretty appalled at the life of a nurse too, and yet I felt so drawn to it. I wanted to make a difference in the world and to help people who needed care and compassion. When my grandfather had been very sick it had been me who sat with him, comforted and cared for him, not my brothers and sisters or even my parents, who had been uncomfortable around illness. It felt to me it was the right thing to do; it felt like it was my gift to him. But even my friends hadnt thought nursing a worthwhile ambition nice privately educated young ladies werent meant to do that sort of thing (unless you count my heroine Florence Nightingale, of course).