Chapter One

Fox Hunting for Beginners

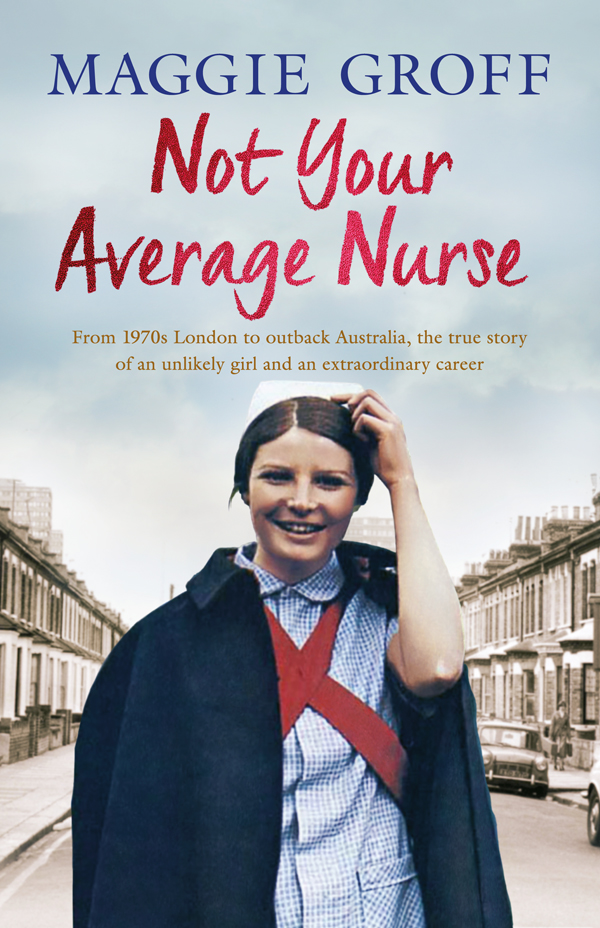

A teaching hospital in London: September 1970

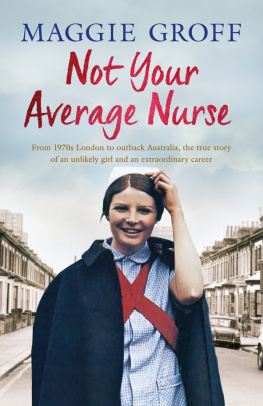

Big trouble awaited me on my first day on the job, but I wasnt a bit surprised. The god of bright young things has always had a custard tart ready to smack in the face of a girl like me.

Green as a spring twig, Id completed two weeks of basic nursing instruction in a classroom and was spending a supervised morning on a ward, one of several such half-days that would occur before the end of two months Preliminary Training School (PTS), if I lasted that long.

You elderly men need to look neat and tidy, I told Mr Snape as I straightened his top sheet.

Oh, go away, you stupid girl, he snarled. Ive got socks older than you! Sticking out a determined chin, he messed up the sheet and childishly kicked his legs about.

Challenged, I threw him the death stare Id perfected in 1957 in the playground at Castle Street Primary School. In return, Snape launched his version of the same look he had perfected in 1916 in the war-torn trenches of the Western Front. Back and forth our faces raged until, totally outclassed, I turned away.

To the casual observer, I was a fresh-faced eighteen-year-old girl, dressed in a newly minted Kings College Hospital student-nurse uniform. My crown was a paper cap attached to my strawberry-blonde up-do with hairgrips, and my overly long, blue-and-white-striped waisted dress was protected from germ warfare by a starched white apron that could stand up on its own.

From my perspective, I looked fabulous very cool and now and the only problem with the image was that I wasnt actually at Kings College Hospital. Somehow a terrible mistake had occurred and I was standing in what appeared to be a dilapidated eighteenth-century school hall, but was in reality a male geriatric ward at St Giles Hospital in Camberwell, an area of South London classified as a Poor Law parish in 1835. And not much had changed.

Formerly a workhouse for the destitute, St Giles had been developed into an infirmary about a hundred years before I arrived, and its present state of crumbling antiquity was three moons and a shooting star away from the grandeur and excitement of Kings College Hospital in Denmark Hill, where I was supposed to be. I planned on writing a stern letter when I discovered who was responsible for this appalling mix-up.

Around me on the ward, which was unimaginatively identified by a capital letter and a number, and which I am rechristening Dickens, courtesy of the workhouse connection, the air was filled with groans, vocal complaints, death-rattling coughs and unpleasant odours.

Scurrying about in this oppressive atmosphere, second- and third-year student nurses delivered bowls of steaming water, pulled curtains around beds, lifted men onto wheelchairs and pushed them here and there, filled things, emptied things, and wrestled with trolleys and oxygen cylinders. Frustrated that a staff nurse had directed me to pointlessly tidy top sheets, I observed the other nurses purposeful industry with mounting annoyance.

Another new student nurse, Fenella, was also on Dickens. A tall, dark-haired girl with lovely apple cheeks and a plummy voice, Fenella wouldnt have been out of place on a hockey field at an English boarding school. On arrival, she had been dispatched to the clinical room to clean lotion cupboards, and I was pleased it was her, not me: I would have broken a bottle of rare potion from the Amazon that had cost a hundred pounds. I was safer with sheets. Its pretty hard to break sheets.

I was straightening the bedding of a sleeping man when a cross-looking woman in a green sisters uniform marched onto the ward and headed towards me. Short and scrawny, with a malignant fierceness behind her steel-grey eyes, she was identified by her name badge as Sister Morag, the ward sister who was to supervise me.

Good morning, Sister, I said with the confidence of someone who has practised the line while watching Dr Finlays Casebook . Surely now I would be allocated a sensible job.

Sister Morag frowned. Uh-oh maybe she thought this sheet-tidying lark was my idea.

Staff Nurse told me to tidy sheets, I said accusingly and scoffed for good measure.

Its important for beds to look tidy, she said sharply. And when youve finished that, you are to disinfect everything in the sluice, scrub the bath and bowls in the bathroom, wash the tooth mugs and spittoons, clean the flower vases, wet-dust the patients bedside lockers and then prepare the kitchen trolley for the patients morning tea.

Hmmm. That didnt sound right. Shouldnt I be bed-bathing patients and taking temperatures? Practising things I had learned in class? Nothing she mentioned required supervision or special instruction. I mean, I already knew how to clean. Who didnt?

Genuinely puzzled, I asked, Is it the cleaners day off?

Wham! Pow! Zing!

Wrong question, Maggie. Sister Morag narrowed her eyes and pressed her thin, bloodless lips together. Thrusting out a furious pointy finger, she ordered, Get to work!

Now, heres the thing: I was already standing where I needed to be, so what was I supposed to do? Thankfully, flight mode kicked in and I walked swiftly away. And I kept walking until Sister Morag disappeared into her office to breakfast on bullets and eye of newt.

Left to supervise myself, and scared that every patient might have a heart attack, I cautiously approached the nearest bed. Cleverly, I checked the patients name on the label clipped to the iron bed head. Plaques identifying the consultants names were displayed above the beds. Like religious icons.