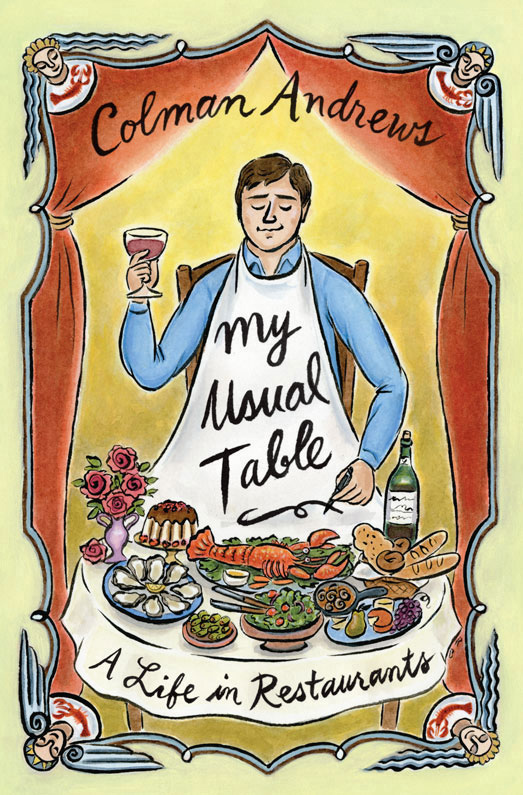

For Joan Luther (19282011), who knew restaurants better than anyone

La tavola mezza confessione.

TUSCAN PROVERB

CONTENTS

Im walking down the street in an unfamiliar city. Its dark, a little chilly, a little past most peoples dinnertime. The stores are closed. A few cars prowl by, and a delivery van idles at the curb, but theres almost no one on the sidewalksjust a woman in gym clothes walking a dog, say, and maybe a couple of late workers crossing from their office building to the parking garage. I round a corner, heading vaguely back to my hotel, and catch the faint scent of grilled meat in the air. I havent eaten, and it draws me like the aroma of an apple pie cooling on a windowsill used to draw young miscreants in old cartoons. I keep walking, following my nose, until I see, at the end of the next block, an inviting low-slung building with a big red door and a row of half-curtained windows through which a warm glow seeps. As I get closer, a smiling couple comes out of the place, and for a few seconds, before the door eases shut, I hear from inside a familiar dinthe clatter of plates and glasses, the hum of conversation. I walk straight to the door and step inside. A willowy young woman in her twentiesor maybe its a stocky, well-dressed gentleman thirty years her seniorgreets me, reassures me that the kitchen is still open, and shows me into the dining room. I sit down, unfurl the napkin, order a Hendricks martinivery cold, please, with a twistand pick up the menu with as much agreeable anticipation as a crime-novel buff opening the latest Michael Connelly. Im perfectly content, and for a very good reason: Even though Ive never been here before, Im at home.

I GREW UP IN RESTAURANTS. I dont mean that my parents owned or ran themmy father was a Hollywood screenwriter, my mother a onetime ingenue turned housewife and society damebut they practically lived in restaurants themselves, and when they went out to eat, they often took me with them. Some of my earliest memories are of perching on a booster seat in a red or green leather booth at a table covered in thick white napery and crowded with silverware and glasses, and being waited on and fed and plied with Shirley Temples and told to sit up straight. I can still summon up a sensory impression of those evenings, romanticized, of course, and with the particulars of each occasion blurred hopelessly together, but vivid nonetheless: the ceaseless motion all around me, a choreography of waiters and busboys, arriving and departing guests; the reassuring clamor that suggested room-wide concord and contentment; the aromas intertwining in the aircigarette smoke, Sterno, sizzling meat, coffee, the iodine-scented whisky in my fathers glass, the floral sweetness of my mothers best perfume. It all washed over me, and never really went away.

At far too young an age, Im sure, I fell in love with restaurants, and it was that love that ultimately led me to where I am today. My entre, if youll pardon the expression, into the world of what I later would call gastronomy came through the dining room, not the kitchen. I liked the food, certainly, but I also liked the ritual, the folderol, the whole experiencethe way a place looked and felt, the friendliness and efficiency of the staff, the variety of choice, even the little sensory accents: the heft of the water glass, the dancing light of the table candle, the luxurious sensation of wiping greasy fingers on soft linen.

Eventually, almost accidentally, I found a way to turn my love for restaurants into a careerinto, really, a way of life. When I first started to think seriously about that way of life and where it had taken me, it occurred to me not just that restaurants have been a constant for me but also that at virtually every stage of my existence, there has been at least one restaurant at the center of things for me, both literally and symbolically. This is a book about those restaurants, and about my life in and around them. Theyre a diverse bunchsome, world-famous temples of haute cuisine; others, more notable for their character or their clientele than for their cooking. All too many of them have vanished. Ive picked them out for present purposes because they have been touchstones for me, personally and professionally, but also because they represent something, different in every case, about the history and culture of food in America and Western Europe. They are places that in some way help define who and what I was and have become, but that are also, for the most part, emblematic of the revolutions great and small, over the past half century or so, that have changed the way we eat and cook and think and feel about food.

M Y PARENTS WERE THE PERFECT RESTAURANT goers: Dad made good money writing screenplays and Mom couldnt cook. They loved dining out, loved dressing up and hobnobbing, loved getting their names in what were then called the society pages, and they went to all the best and smartest places in Los Angeles. They had courted at one of the most famous local restaurants of them all, the legendary Romanoffs in Beverly Hills. Romanoffs was a glamorous movie-business bote presided over by a onetime Lithuanian pants presser who had reinvented himself as a Russian prince; the menu offered beluga caviar, frogs legs, calfs brains, and the slightly naughty-sounding Devilled Turkey Casanova for Two, and everyone who mattered in Hollywood ate there.

I never got taken to Romanoffs, for whatever reasons, but I went along almost everywhere else: the always bustling Hollywood Brown Derby, hung with charcoal caricatures of the same stars who were frequently sitting at various booths around the room; the cool and clubby Tail o the Cock on La Cienega Boulevards Restaurant Row, where I discovered swordfish and sand dabs and drank fruit punch (and much later French 75s) out of tall frosted glasses; the handsomely appointed Beverly Hills Hotel dining room, where I ate prime rib au jus (pronounced o juice), carved from a silver-domed gueridon by a white-haired chef named Henry; the stylish Kings in West Hollywood, where I saw my first live lobsters, languishing in big glass tanks against one walland found, probably to my parents surprise, that the notion of picking out my dinner while it was still moving didnt bother me at all.

Not everything was fancy. Dad took me to lunch at the commissary at whichever studio was employing him, and to film-business haunts like Oblatts, a few feet from the Paramount Studios gates, where Id delight to see cowboys and Indians and Romans and medieval dukes in full costume and makeup slurping spaghetti at the counter, and Luceys, a sprawling mock-adobe place across the street from Paramount, where I appreciated the Monte Cristo sandwiches (and where, Dad once told me, more careers have been made and ended than on any movie lot in town).

Mom fed me at department store tearoomsWaldorf salad or cream cheese sandwiches on walnut-raisin bread, while I perched on wrought-iron chairs with pastel cushionsand at drugstore lunch counters, institutions that today have all but vanished, where Id spin my stool from side to side and order a cheeseburger or a breaded veal cutlet and a milk shake made before my eyes in one of those splendid chrome-and-pistachio-green Hamilton Beach contraptions. If I was good, Id get taken to Blums in Beverly Hills, an outpost of the San Francisco original, where the main attraction was a kind of devils salad bara do-it-yourself sundae cart wheeled around to every table, loaded with six or eight different kinds of ice cream and with toppings of every sort, from hot fudge and butterscotch to nuts, whipped cream, and nonpareils, to be assembled and combined and gloriously overdone at will. I loved it all.