Table of Contents

Portions of An Interview with Dario Argento appeared in a different form in Gorezone.

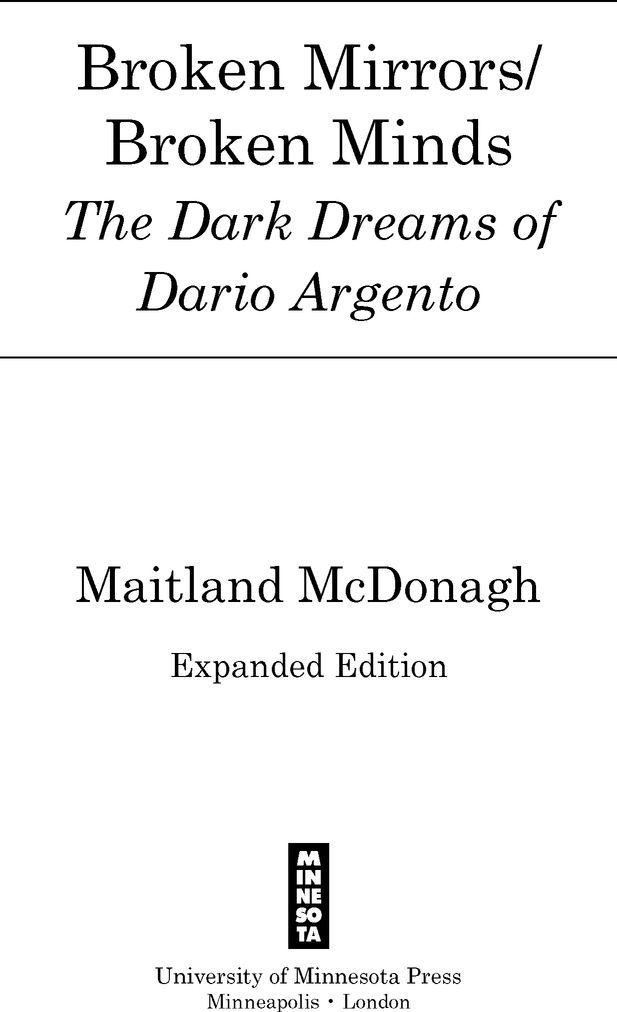

Copyright 1991, 1994, 2010 by Maitland McDonagh

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McDonagh, Maitland.

Broken mirrors, broken minds : the dark dreams of Dario Argento / Maitland McDonagh.Expanded ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : Sun Tavern Fields, 1991.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8166-5607-3 (pb : alk. paper)

1. Argento, DarioCriticism and interpretation. 2. Horror filmsItalyHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN1998.3.A74M37 2010

791.430233092dc22

2010004140

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

INTRODUCTION HEART OF DARKNESS: TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY NIGHTMARES

By 1976, I had seen plenty of Euro-thrillers, but I had never seen anything like Deep Red. It wasnt the story that stuck with me months, and then years, after I encountered it at the Victoria, a shabby, once-grand movie theater on Forty-sixth and Broadway. It was the overwhelming visceral experience of it, equal parts visualvivid colors and bizarre camera angles, dizzying pans and flamboyant tracking shots, disorienting framing and composition, fetishistic close-ups of quivering eyes and weird objects (knives, dolls, marbles, braided scraps of wool)and aural. Deep Reds throbbing progressive-rock score was almost hypnotic, and alternated with a singsong lullaby whose la la la la lyrics grew more gratingly ominous with each repetition. For all the baroque murder sequences, the devilish hook was in the details: the ghoulish cluster of paintings on a murdered womans wall; the hanged baby doll; the childish scrawl depicting a bloody murder, scribbled on the wall of a crumbling palazzo; and that cackling mechanical doll, flailing on the floor with its head cracked open. More than a decade later my fascination with Argentos baroque world of horror produced the first edition of Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds: The Dark Dreams of Dario Argento, but this is where it all began.

I was born at the end of the baby boom and came of age as the flower-child optimism of the 1960s was curdling into paranoia, cynicism, and self-destruction. The New York in which I grew up was a great city in decay, and Times Square was still Hells midway rather than a corporate theme park. It was, of course, not what it used to be, because Times Square was never what it used to be: no matter what year you started prowling the once lavish theaters long gone to seed, there was someone eager to say you should have seen it when. But trust me: in 1974, when I ventured into the Selwyn for a double bill of the Amicus horror/blaxploitation/action hybrid The Beast Must Die and Seizure (the film that didnt make Oliver Stone a household name) the Deuce was still wild.

The house lights were always half up, presumably so the projectionist could keep an eye on what was going on, though I never saw anyone actually do anything about anything that went on. Dealers walked the aisles selling drugs from makeshift string and cardboard trays, like cigarette girls in old movies; hookers took naps and people unpacked full meals or dried their laundry on the backs of seats. The scene was simultaneously sordidly Dickensian and oddly homey.

Back in the good old/bad old days, Times Square theaters were an international smorgasbord of sleaze, and I took full advantage of its offerings. I sampled movies by Lucio Fulci, Joe DAmato, Paul Naschy, Antonio Margheriti, Umberto Lenzi, Fernando di Leo, Sergio Martino, Cirio H. Santiago, and Ulli Lommell, along with the homegrown likes of Al Adamson, Ted V. Mikels, Fred Olen Ray, and many, many others. Dirtcheap double and triple bills are a great way to expand your moviegoing horizons.

I saw bizarro-world pairings like Barbara Peeterss mutant amphibious rapist picture Humanoids from the Deep and Brian De Palmas Dressed to Kill . I saw the hallucinatory Dead People , by future George Lucas collaborators Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, and David Cronenbergs first four features, each of which managed to stun rowdy thrillseekers into silence at least once.

I saw the notorious killer-Santa movie Silent Night, Deadly Night (which, frankly, bored Times Square regulars as much as it outraged Midwestern moms and dads) and the much-reviled Last House on Dead End Street at the two-screen Cine 42, a shoebox of a grindhouse so dirty, claustrophobic, and relentlessly seamy that I remember it more vividly than the movieespecially the upstairs theater, where you had to choose between sitting up front, close to the exit but with your back to whatever was transpiring in the other rows, or further back, where you could keep an eye on the other patrons but ran the risk of finding trouble between you and the only way out, like the fellow who was stabbed to death there in 1982.

What I didnt see was much Argento. Aside from Deep Red, the only one of his films I ran across during those years was The Bird With the Crystal Plumage when it was briefly re-released as The Phantom of Terror in the early 1980s; neither played Forty-second Street. Yet while most of the shockers I pursued so relentlessly almost immediately retreated into a blur of flesh-eating zombies, baroquely deranged killers, and hokey monsters (I can hardly believe goofy creature features like Spawn of the Slithis and Blood Beach were getting theatrical releases alongside boundary-pushing sex-and-violence titles like Thriller: A Cruel Story ), Argentos films, especially Deep Red , staked out a place in my memory. Years later, snatches of the infernally catchy score by Goblin (a shifting collection of prog-rockers Argento brought together for Deep Red and with whose various members he continued to work for three decades) occasionally floated through my thoughts and triggered images as elusive and haunting as the sticky threads of a dream.

In 1985 I was in the home stretch of Columbia Universitys MFA program, pursuing a degree in film history/theory/ criticism and desperately trying to come up with a thesis topic. I didnt want to spend a year writing something I didnt want to read. I wanted to write about horror, but I wasnt interested in parsing the minutia that earlier generations of graduate students had left clinging to the bones of Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or forcing some trendy academic framework on James Whales Bride of Frankenstein or the Hammer Dracula films

So when a friend suggested a study of Dario Argentos films, a light went on. On the strength of Deep Red (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage hadnt made much of an impression) I started researching and found that while there was plenty of writing about the man and his films, including newspaper reviews, interviews and on-set features in genre magazines, and one-off tributes with a high picture-to-text ratio, there was nothing academic. The field was clear, and Argentos films were a graduate students dream, penny-dreadful narratives seething with subtext and vibrating with visual virtuosity. There was so much to write about.