Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

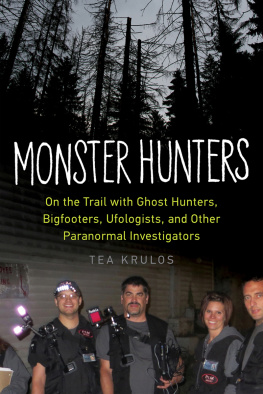

GHOST HUNTERS

Deborah Blum is a professor of science journalism at the University of Wisconsin. She worked as a newspaper science writer for fifteen years, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for her writing about primate research, which she turned into a book, The Monkey Wars. Her other books include Sex on the Brain and Love at Goon Park. She has written about scientific research for the Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, Discover, Health, Psychology Today, and Mother Jones. She lives in Madison, Wisconsin, with her husband, two sons, and a very large boxer.

To the sisterhood-Darcy, Dawn, and Dana

PRELUDE

NO ONE SAW the girl die. It was just a little too early, a morning still too dark, first light barely warming the edge of the sky. The night frost yet shimmered on the ground, a faint ghostly silver. It was barely 6:00 a.m. on a late October morning when sixteen-year-old Bertha Huse stepped out into the quiet. Her parents and her sister were still asleep in the small house they shared in Enfield, New Hampshire.

Later, a few of the town folk, those like the blacksmiths wife who were up doing morning chores, recalled seeing the girl go by, tying her bonnet as she went. She was a familiar sight, catching a quick walk before she started her mill job. The blacksmiths wife watched Bertha turn toward the lake. She left a trail of footprints on the frosty dirt road, but they vanished as the sun climbed higher and warmer.

When their child didnt come home, her parents were at first puzzled. Then a little worried. And slowly, as the sky lightened and the morning quickened, they became frantic. They were out calling for her, hunting down the empty road to the shores of the silent lake. As it became obvious that something was really wrong, their friends and neighbors joined in. By days end, the searchers numbered more than a hundred and fifty people, calling ever louder, rattling through empty thickets and fields, more and more of them glancing toward the polished blank of the water.

The dirt road led to an old Shaker bridge, a structure of wooden boards, without railings, offering a simple passage across Mascoma Lake. The lake was longer than wide, clear gold at its edges, darker at its center where the water deepened, shining like an agate set into the burnished hills. Around the bridge though, the water turned opaque, clotted with weeds growing around the wood, dropping to a black depth of eighteen feet. The searchers found no trace of the girl, not in the woods, in the clear shallows, or around the bridge where the water gleamed as a dark mirror, reflecting only the worried faces.

Finally, the mill owner himself sent for a diver from Boston to explore around the Shaker bridge. The diver, suited against the cold of the lake, slid down, disappearing himself like a stone beneath the surface. Again and again he tried, until his leather suit was sodden and his glass bubble helmet filmed with lake water. But he didnt find the girl either. It was as if Bertha had vanished into the dawn itself. There was nothingexcept the nightmare that caused a woman in a nearby town to start screaming in her sleep.

GEORGE AND NELLIE TITUS lived almost five miles away, down lake, in the mill town of Lebanon. Like Bertha, George worked in one of the clothing mills. The workers spread the tale of the lost girl. Everyone knewand worriedabout a missing child. The Tituses talked it over, wondered if they could help.

After supper, Nellie Titus went upstairs and curled into a rocking chair for a nap, pulling a blanket over herself She was asleep when her husband came up the stairs, but she was sitting almost bolt upright, her hands wringing in her lap and her breath coming in gasps. She screamed. Alarmed, he reached over and shook her awake. Her eyes stayed unfocused. But her voice came sharp and unhappy Oh, George, she said. Why did you wake me? A little deeper into the dream, she insisted, she could have told him where that girl was. He shook his head. It was a nightmare, he said, you were screaming. Dont wake me again, she answered, almost pleading. No matter what I do in my sleep.

The dreams haunted them both for another day. Bertha Huse had disappeared on a Monday morning. That Thursday, George Titus gave up on sleep at 1:00 a.m. He lit a lamp and turned toward his wife. She was shivering now, teeth chattering. Are you cold, Nellie? he asked as he pulled the quilt up. Oh, oh, I am awfully cold, she answered, and then she slid silently down into the bed. When she woke, the dawn was once again breaking against the blackness of the night. We have to go to the Shaker bridge, she told her husband.

He was almost too exhausted to argue. And anyway, she was scaring him. Titus went to the stable where he kept a horse and told the stable master, almost casually, that his wife had dreamed the answer to the missing girl. The man laughed, but George Titus shook his head and recounted what she had told him. That Bertha Huse had first appeared on the bridge, hesitating about which way to go. She balanced on a frost-slick board, looking back toward the village. Her foot slipped, and she went backward into the lake. It was about at this point in the dream, he thought, that his wife had begun shaking with cold.

The Tituses drove their buggy onto the bridge. They were more than halfway before she asked to stop. Nellie Titus walked to the edge. George, she said, pointing down the bridge supports. She is right there. He could see nothing but the polished surface of the water, black and glossy as obsidian. He stared at his watery reflection. There was one other thing that he knew, which he hadnt told his friend at the stable. Nellie was the grand-daughter of a known psychic. She didnt claim to be one herself. But shed had these haunted dreams before. They always left her physically ill. She hated them. They came anyway, slipping past her defenses as she slept.

The couple tracked down George Whitney, the mill manager, who was heading up the search team, and hefrustrated and desperatecalled in the diver. The diver was a slim, wiry Irishman named Brian Sullivan. He thought they were all crazy. Sullivan worked for the Boston Tow-Boat Company, and hed been diving for bodies for years. Bodies were sometimes hard to find, thats all. That was reality. Dreams werent. Whitney told him that he didnt believe in such dreams either. They were both rational men, he assured Sullivan; they both agreed that ghosts did not really creep into dreams.

But Whitney knew people in the village who were less rational. There were those who did believe in visiting spirits. And he told Sullivan, As long as we have started to do all we could to recover the body, we ought to at least give this woman a chance.

Sullivan continued arguing. He wanted to send to Boston for blasting powder and set off an explosion that would shake the girls body loose from the lake bottom, if it was there. He told Whitney that he was willing to take ordersbut he did not want make a fool of himself, splashing in and out of the lake while Mrs. Titus spouted mystical nonsense and pointed at assorted dream spots. Whitney conceded the point. He had no intention of looking ridiculous either. They would give her one chance only.