In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Copyright 1999 by Peter Guralnick

Cover design by Michael Ian Kaye. Cover photograph from the Lynn Goldsmith Collection. Cover copyright 2012 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All photographs are copyrighted by the photographer and/or owner cited, all rights reserved.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

peterguralnick.com

First e-book edition: December 2012

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-20672-3

For Jacob and Nina and for Alexandra

Its difficult to be a legend. Its hard for me to recognize me. You spend a lot of time trying to avoid it. The way the world treats you is unbearable. Its unbearable because time is passing and you are not your legend, but youre trapped in it. Nobody will let you out of it except other people who know what it is. But very few people have experienced it, know about it, and I think that can drive you mad. I know it can. I know it can.

James Baldwin, interviewed by Quincy Troupe

THIS IS A STORY of fame. It is a story of celebrity and its consequences. It is, I think, a tragedy, and no more the occasion for retrospective moral judgments than any other biographical canvas should be. Suspending moral judgment is not the immorality of the novel, Milan Kundera wrote in what could be taken as a challenge thrown down to history and biography, too. This suspension of judgment is the storytellers morality, the morality that stands against the ineradicable human habit of judging instantly, ceaselessly, and everyone; of judging before, and in the absence of, understanding. It is not that moral judgment is illegitimate; it is simply that it has no place in describing a life.

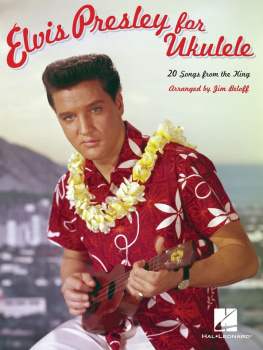

Elvis Presley may well be the most written-about figure of our time. He is also in many ways the most misunderstood, both because of our ever-increasing rush to judgment and, perhaps more to the point, simply because he appears to be so well known. It has become almost as impossible to imagine Elvis amid all our assumptions, amid all the false intimacy that attaches to a tabloid personality, as it is to separate the President from the myth of the presidency, John Wayne from the myth of the American West. Its very hard, Elvis declared without facetiousness at a 1972 press conference, to live up to an image. And yet he, as much as his public, appeared increasingly trapped by it.

The Elvis Presley that I am writing about here is a man between the ages of twenty-three and forty-two. His circumstances are far removed from those of the boy whose dreams came true in the twenty-second year of his life. It is not simply that his mother has died, testing his belief in the very meaning of success. With or without his mother by his side, he would have had to grow up; he would have had to face all the complications of adulthood in a situation of almost unbearable public scrutiny, a young man little different in temperament from the solitary child who had constructed a world from his imagination. The army was hard for him not just because he was temperamentally unsuited to it but because it was something he knew he had to succeed at, both for himself and for others. The artistic choices he faced when he returned to an interrupted life were far more ambiguous than the good fortune he had so innocently embraced, and he never came fully to terms with the burden of decision making that those choices placed upon him. His natural ability to adapt, his complex relationship with a manager whom he perceived not just as a mentor but as a talisman of his good luck, served him in both good and bad stead. He constructed a shell to hide his aloneness, and it hardened on his back. I know of no sadder story. But if the last part of Elvis life had to do with the price that is paid for dreams, neither the dreams themselves, nor the aspiration that fueled them, should be forgotten. Without them the story of Elvis Presley would have little meaning.

Ive tried to tell this story as much as possible from Elvis point of view. Although he never kept a diary, left us with no memoirs, wrote scarcely any letters, and rarely submitted to interviews, there is, of course, a wealth of documentation on the life of Elvis Presley, not least his own recorded words, which, while seldom uttered without some public purpose, almost always offer a glimpse of what is going on within. Ive pursued contemporary news accounts, business documents, diaries, fan magazines, critical analyses, and the anecdotal testimony of friends and eyewitnesses not with the intention of imposing all this on the reader but simply to try to understand the story. In the end, of course, one has to cast aside the burden of accumulation and rely on instinct alone. There is always that leap of faith to be made when you accept the idea that you are painting a portrait, not creating a web site. Certainly you have to allow your gaze to wander, it is essential to take every possibility into account, not to prejudge either on the basis of likelihood or personal biasbut you also have to recognize that with the angle of perception changed by just a little, with a slightly different selection of detail, there may be an altogether different view. This is where the leap of faith comes in: at some point, you simply have to believe that by immersing yourself in the subject you have earned your own perspective.

I have spent eleven years with Elvis. Much longer if I go back to the pieces I originally wrote to try to tell the world why I thought his music was so vital, exciting, and culturally significant, how it was part of the same continuum of American vernacular music that produced Robert Johnson, Hank Williams, Sam Cooke, the Statesmen, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Golden Gate Quartet. I still think thatbut immersion in the subject has changed my view in other, more subtle ways. Once I saw Elvis as a blues singer exclusively (that was my own peculiar prejudice); now I see him in the same way that I think he saw himself from the start, as someone whose ambition it was to encompass every strand of the American musical tradition. And if I am still not equally open to his approach to every one of those strands, I can at least say that I have awakened to the beauty of many of the ballads I once scorned and come to a new appreciation of the gospel quartet tradition that Elvis so thoroughly knew.