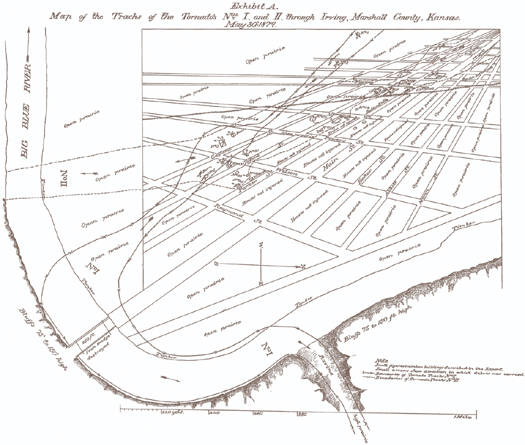

Endpaper map reprinted from Professional Papers of the Signal Service, No. IV: Tornadoes of May 29th and 30th, 1879, in Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri, and Iowa, by Sergeant J. P. Finley. Courtesy of Robert J. Herman, Wamego, Kansas

For a larger version of this map, click here.

STORM KINGS

Copyright 2013 by Lee Sandlin

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada

by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sandlin, Lee.

Storm kings : the untold history of Americas first tornado chasers / Lee Sandlin.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-90816-2

1. Tornadoes. 2. Storm chasers. I. Title.

QC 955. S 26 2013 551.553092273dc23 2012027314

Endpaper map reprinted from Professional Papers of the Signal Service,

No. IV: Tornadoes of May 29th and 30th, 1879, in Kansas,

Nebraska, Missouri, and Iowa,

by Sergeant J. P. Finley. Courtesy of Robert J. Herman, Wamego, Kansas.

www.pantheonbooks.com

Jacket image: The Recent Cyclone in Ohio, 1884,

from Harpers Weekly, Corbis

Jacket design by Kelly Blair

v3.1

For Joanne Fox

toujours fidle

The wind blows as it wills, and you hear the sound of its passage, but you cannot say where it comes from or where it goes.

This is how it is for the children of the wind.

John 3:8

The wind blows over the lake and stirs the surface of the water. Thus visible effects of the invisible manifest themselves.

I Ching, hexagram 61, Inner Truth,

Wilhelm/Baynes commentary

He cometh in terror, the vast mountains shake,

The citadel flames, and earths huge pillars quake;

The proudest achievements of man are his spoil,

He wars with the forest, and tears up the soil

The grandest, the strongest, the stateliest thing,

Must bow to the nod of the Old Storm King.

G. Linnaeus Banks,

Bentleys Miscellany, 1847

Contents

Introduction

Ghost Riders

There is an old country-and-western song my father liked called Ghost Riders in the Sky. My father had been born and raised in rural Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl years and had spent his adolescence working at cattle ranches in Colorado and Wyoming; in his later life he was fond of saying that he had been one of the last of the old-fashioned cowboys, and he often recited scraps of cowboy poetry or retold the spooky folklore hed heard from the other ranch hands. Ghost Riders in the Sky was a perfect example. Its about a cowboy who has a terrifying vision: he sees the souls of damned cowboys riding through the night in an eternal chase after a stampede of supernatural cattle. One of these spectral cowboys breaks off the pursuit long enough to warn the singer to repent his evil ways, or else, after he dies, he will join them trying to catch the Devils herd across these endless skies.

I dont remember my father ever connecting this stampede to tornadoes. But then, he didnt have to. I made the connection myself the first time I heard him sing the song, and its stayed with me ever since. He was constantly telling me scary stories about tornadoes. He made them sound like a regular feature of his childhood landscape. The way he described it, anywhere on the Great Plains, if you raised your eyes to the horizon, you might somewhere in the vast flat distance see a funnel cloud beginning to form. He talked about all the different and bizarre shapes they took: grand swooping curves of impossible architecture, furious little whirlwinds like the clouds of dust above cartoon fistfights. He repeatedly told me about the closest call hed ever had with a tornadoa blustery summer day when he and his friends had been playing baseball and a tornado had come roaring across the outfield; theyd had to hide in the dugout, clinging to the underside of the bench, to keep from being sucked into the funnel. But his favorite stories were about the nights he and his family had spent cowering in their snug lantern-lit storm cellar as the world outside had torn itself apart in the frenzy of a prairie thunderstorm: at some point his mother would raise a finger for silence, and theyd hear amid the roar of the wind and the crashes and bangs of thunder a sinister new sound, a deep throbbing and a high-pitched shriek like an airplane engine revving up. And that, my father would conclude with satisfaction, was the tornado.

I was spellbound by these stories, but I was also baffled by them. I never got that clear an idea of what a tornado really was. We lived then in northern Illinois, a place that was supposedly tornado heavy, but I had only seen one unmistakable tornado in my life, and that was in The Wizard of Oz. Few sights in any movie, or for that matter in the real world, have ever scared me as deeply as that. My father had no patience for it, though. He passed through the living room as my mother and brother and I were staring at the television screen in rapt horror, and he lingered only long enough to emit a snort of contempt. Nah, thats no tornado, he said. You should see a real tornado.

Each spring the science class at my elementary school would spend a day on the subject of tornadoes. The teacher would show us a filmstrip that had a lot of cartoon images of spiral-shaped clouds looming over prairie farmhouses. There were also photographs of crew-cut men with white shirts, black ties, and horn-rimmed glasses, clustered in muddy fields around weather balloons. But only a few of the images were of actual tornadoes; in those days, the 1960s, a clear photograph of a tornado was as rare as one of a flying saucer.

The filmstrips narrator instructed us solemnly on the rules of tornado safety. There was one infallible warning sign that a tornado was coming, he said: the clouds took on a greenish glow. Tornadoes also caused an electrical disturbance that could be picked up by some TV sets, so if your TV screen grew mysteriously brighter during a storm, that was a clear signal a tornado was somewhere nearby. Then he explained why tornadoes were so destructive: there was a near vacuum at the heart of the funnel, so when it passed overhead, the air pressure trapped inside your house burst outward like an explosion. The most sensible precaution you could take, therefore, was to open your windows to equalize the air pressure. After you did so, only then should you take shelter, and the one safe place to hide was the southwest corner of the basement.

The viewing of this filmstrip turned me into a kind of amateur tornado warden. Whenever there was a storm, I kept my eyes peeled for the warning signs. But where were they? Spring after spring, tornado season after tornado season, I never saw a hint of a green glow in the sky. The closest I came to a tornado was one sultry April afternoon when I was twelve: a severe storm came through the Chicago suburbs, and a tornado touched down several miles away. The next day the newspapers ran an amateur photograph: it showed a blurry smear of buildings and streetlights, while against the horizon stood an indistinct gray cone of smoke towering up to the sky like a supervillain menacing a cartoon city. I tore it out of the paper and tacked it up on my bedroom wall, as though it were a wanted poster.