In Search of Robert Millar: Unravelling the Mystery Surrounding Britains Most Successful Tour de France Cyclist (HarperSport), 2007

Heroes, Villains and Velodromes: Chris Hoy and the British Track Cycling Revolution (HarperSport), 2008

Slaying the Badger: LeMond, Hinault and the Greatest Ever Tour de France (Yellow Jersey), 2011

Skys the Limit: British Cyclings Quest to Conquer the Tour de France (HarperSport), 2011

Lewiss humiliations on the sports field would find an echo over three decades later, in 2003, when he was invited to pitch the ceremonial first pitch in a major league baseball game. His effort was pitiful; the ball dribbled out of his hand and bounced three times before it reached the plate. The case could easily be made that hes the greatest athlete of the twentieth century, noted the commentator, but he sure as hell cannot throw a baseball.

He was wrong: Lewis never did hold the record. Bob Beamons famous leap of 8.90 metres at the 1968 Olympics lasted until Mike Powell achieved 8.95 metres in 1991, which still stands more than twenty years later.

The Welshman who won the 1964 Olympic long jump gold. He became technical director of the Canadian Track and Field Association but, unsurprisingly, not for long.

Donike told the Dubin Inquiry in 1989 that two athletes were positive for testosterone in Helsinki, but that theyd been cleared because it was decided their urine samples were too dilute. He didnt name the athletes.

Diane Clement, who competed in the 1956 Olympics, had stood for election to the IAAF ruling council in 1972, only narrowly losing. The man who scraped on to the council instead was Primo Nebiolo. Had Clement beaten Nebiolo, the sports history might have been very different.

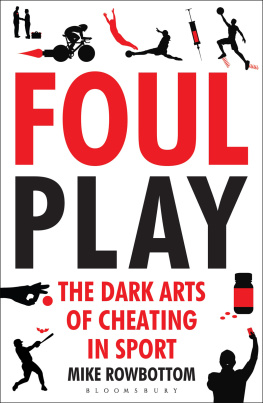

Probenecid was at the centre of controversy at the following years Tour de France, when the overall leader, Pedro Delgado, tested positive. Although by then banned by the IOC, Probenecid had not yet been added to cyclings banned list. Delgado was exonerated and won the Tour.

A British Athletics Federation investigation into this affair, chaired by Peter Coni, QC, cleared Norman, though he appeared to incriminate himself by claiming: I wouldnt put myself in jeopardy for an athlete of his standard. This, said Coni, left open the glaring corollary that for an athlete of a very different standard, very different considerations might apply.

Beckett was right about HGH: a test was not developed until 2008, with only a twenty-four-hour window of detection. Another new form of doping discussed at length during the conference was abortion doping. Delegates alleged that some female athletes had been artificially inseminated and then had the foetus aborted after three months to receive a hormone boost. De Mrode said he had heard of a Swiss doctor who performed this service.

Two decades later, he fronted an advert for Kleenex pocket tissues using the line: Ive got a tiny packet.

Rob Woodhouse, an Australian swimmer at the Seoul Games, recalls a popular joke among the athletes when Testing, Testing, was announced over the public address system in the canteen in the athletes village. When they said testing, the 100m sprinters couldnt be seen for dust.

At Beijing in 2008, the swimming finals were held in the morning but not the athletics, reflecting the US teams changed strengths and the audiences changed priorities.

A claim Don Catlin describes as nonsense.

On 8 July 1991, Johnson and Lewis had a much-publicised re-match in Lille, northern France. Johnson finished seventh in 10.46; Lewis ran 10.20 to finish second to Dennis Mitchell.

Johnson was stripped of the 1987 world title following his doping confession at the Dubin Inquiry, and of his 1988 Olympic title after testing positive in Seoul. The score, before Johnson was disqualified from these races, read: Johnson: 7, Lewis: 10.

Stripped of world record for doping.

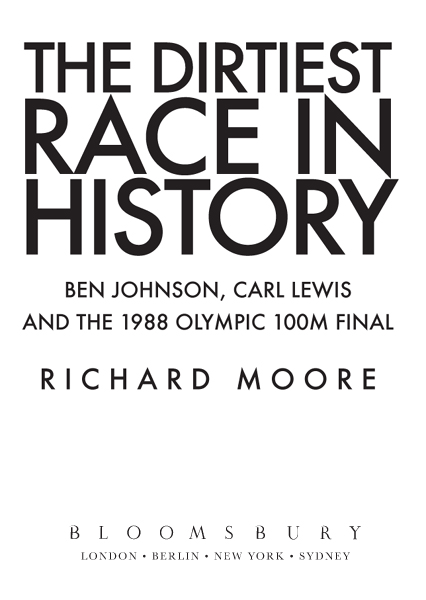

To Virginie

First published in Great Britain 2012

Copyright 2012 by Richard Moore

This electronic edition published in 2012 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. Image on pp. viiiix courtesy of Getty Images. Image on 301 used with permission of Philadelphia Inquirer copyright 2012. All rights reserved.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3DP

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, Berlin, New York and Sydney

www.bloomsbury.com

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4081 7111 0

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

This is a story mainly about four extraordinary men: Ben Johnson, Carl Lewis, Charlie Francis and Joe Douglas. Johnson and Douglas were both willing interviewees and could not have been more helpful. Francis, Johnsons coach, died in 2010. And Lewis, well, he proved so elusive that the title almost became In Search of Carl Lewis.

I tried to contact him through his agent, who, in the course of my efforts, became his ex-agent. I tried his sister-in-law, who acts as his manager; she didnt return emails or phone calls. I tried friends. But finally I met him: in a shop on Oxford Street in London. It was a strange, though somehow fitting, encounter.

A word about the title, too the dirtiest race in history? I mean this in the broadest sense, referring not only to drugs, but also to varying degrees of skulduggery and corruption, and the enduring legacy of the Olympic 100m final in Seoul. There are those who take a more ambiguous, even ambivalent, view. It was the greatest race of all time, they say. And perhaps it was.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity.

A TALE OF TWO CITIES, CHARLES DICKENS

THE GREATEST RACE OF ALL TIME?

SEOUL, SATURDAY 24 SEPTEMBER 1988, 1.20 P.M.

Ben Johnson, hands on hips, stares at the lane ahead of him, his pose giving him a studied casualness, which is in contrast to the lowered head, squinting eyes and dilated pupils. His expression suggests he is staring not at a hundred-metre stretch of rubberised track, but at someone who has just challenged him to a fight.