Copyright (c) 2013 Time Inc.

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED and SI are registered trademarks of Time Inc. Used under license.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

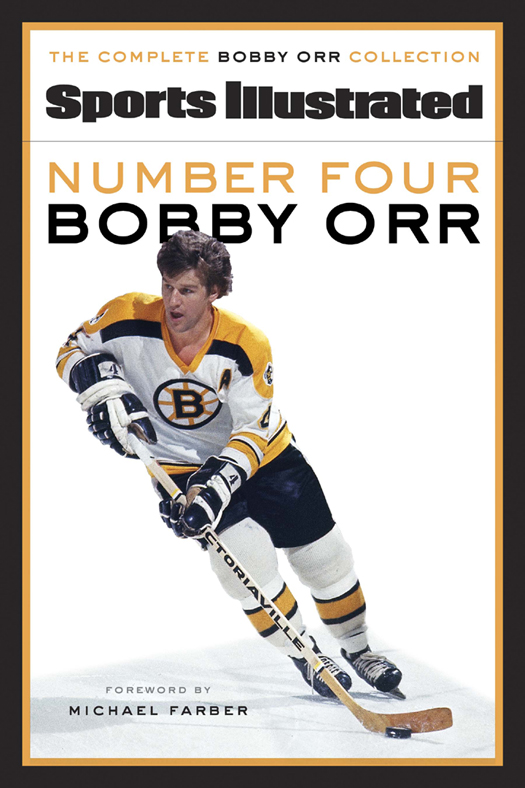

Number four, Bobby Orr : the complete Bobby Orr collection / Sports illustrated ; foreword by Michael Farber.

eISBN: 978-0-7710-7926-9

1. Orr, Bobby, 1948-. I. Hockey players Canada Biography. II. Hockey Biography. III. Title: Sports illustrated

GV848.5.O7N84 2013 796.962092 C2013-900685-0

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by Fenn/McClelland & Stewart, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, P.O. Box 1030, Plattsburgh, New York 12901

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013931557

Fenn/McClelland & Stewart, a division of Random House of Canada Limited One Toronto Street

Suite 300

Toronto, Ontario

M5C 2V6

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY MICHAEL FARBER

A HIGH PRICE FOR FRESH NORTHERN ICE

BY FRANK DEFORD OCTOBER 17, 1966

YOU GOTTA HAVE SOCK

BY PETE AXTHELM DECEMBER 11, 1967

BOBBY STAKES AN ORR CLAIMFOR EVERYBODY

BY MARK MULVOY SEPTEMBER 2, 1968

ITS BOBBY ORR AND THE ANIMALS

BY MARK MULVOY FEBRUARY 3, 1969

BOBBY MINES THE MOTHER LODE

BY MARK MULVOY JANUARY 12, 1970

MR. O AND THE SACK OF NEW YORK

BY MARK MULVOY APRIL 27, 1970

TEA PARTY OF BOBBYS BRUINS

BY GARY RONBERG MAY 4, 1970

SPORTSMAN OF THE YEAR

BY JACK OLSEN DECEMBER 21, 1970

WHATCHA DOIN, BROTHER BRUIN?

BY MARK MULVOY JANUARY 3, 1972

TOUGH MOUNTAIN TO CLIMB

BY MARK MULVOY MAY 15, 1972

AN ICEMAN TOO HOT TO HANDLE

BY MARK MULVOY MAY 22, 1972

OVERDUE ORRGY FOR THE BRUINS

BY MARK MULVOY DECEMBER 11, 1972

DOUBLE JEOPARDY FOR THE BRUINS

BY MARK MULVOY NOVEMBER 19, 1973

BYE-BYE BOSTON, CHICAGO BUYS

BY J.D. REED JUNE 21, 1976

RETURN OF THE FABULOUS INVALID

BY PETER GAMMONS OCTOBER 18, 1976

WHEREVER YOU FIND ORR, HE GLITTERS

BY PETER GAMMONS JANUARY 24, 1977

OH, FOR THE ORR OF YORE

BY JERRY KIRSHENBAUM OCTOBER 9, 1978

THE EVER ELUSIVE, ALWAYS INSCRUTABLEAND STILL INCOMPARABLE BOBBY ORR

BY S.L. PRICE MARCH 2, 2009

FOREWORD

BY MICHAEL FARBER

THE FIRST TIME I SAW BOBBY ORR ON SKATES WAS November 19, 1966, his rookie season with the Boston Bruins. I took a bus from Providence to Boston, bought a ticket from a scalper for double the face value five bucks for a $2.50 ticket, upper balcony, end arena, at a Boston Garden that seemed old and ratty even then and sat with my mouth agape for 2 hours as Orr ragged the puck around traffic cones draped in New York Rangers jerseys. (He also took time out to fight Vic Hadfield.) He was 18, literally a boy among men but figuratively a man among boys. I never had seen anything like it or anyone like him. I was 15 in 1966, which explains a significant part of it. The golden age of sports is whatever happens when you are 15, an age when impressions in malleable minds are converted to declarative sentences that can be blurted with the certitude that few of us will ever know again. On that long-ago Saturday, from my perch in the oxygen seats, I decided Orr was the best hockey player. Ever. More than four decades and one Wayne Gretzky later (and maybe this is the teenager in me typing) I still have never seen anything like it or anyone like him.

ALMOST FIVE DECADES LATER , THIS IS THE TACIT genius of Bobby Orr: He keeps us young. For my generation he is the last taut strand to our frayed innocence. He is Bobby unbound. Unlike another Bobby, Clarke, the Flyers fearless captain of the 1970s, Orr never dropped the diminutive, never tried to reinvent himself as an all-grown-up Bob. How could he dare? Even in his 60s, Orr has a face that looks like it is on loan from a Giotto cherub. He has not merely aged gracefully; he seems to hardly have aged at all. Orr always has kept the same job-interview haircut at least since the early buzz-cut days and never has lost the gleam in his eye that makes women stare and makes men stand a little taller when he enters a room. If anything, Orr cuts an even more impressive figure now than he did as a player, growing into his good looks the way Joe DiMaggio and Jean Bliveau did. He remains hockeys Peter Pan. He is flying, stick raised in his right hand, rapture and amazement comingling on his unlined face, a suspended-in-midair No. 4, defying the laws of physics and St. Louis defenseman Noel Picard to score the Stanley Cup-winning goal at 40 seconds of the fourth period in the fourth game of the 1970 final. (The photograph, Orr being hoisted by his own Picard, is among the most renowned sports images of the 20th century.) Maybe Orr had bargained with the devil for eternal youth, as I once suggested to Eddie Westfall, a Bruins teammate. If Bobby did, Westfall replied, he paid for it with his left leg.

Orr began his career in the Original Six era. He unhappily concluded it before the gilded age of arthroscopy. Like Mickey Mantle and Gale Sayers, the second question always asked about Orr (the first is: Who was better, Orr or Gretzky?) is What if? Over the course of his career, Orr would have 14 operations to repair his knees, including six major procedures on his left. (He underwent replacement surgery on both knees when he was in his 50s.) Orr played 657 regular-season professional games, 30% of Gordie Howes prodigious total and some 900 fewer than Gretzkys. The sheer statistical weight properly suggests that Gretzky was without peer, the best player in history, but the minds eye blurs the tidiness of the decimal point. It begs debate. Orr accumulated what were unprecedented numbers for defensemen including six straight 100-plus point seasons while winning eight consecutive Norris Trophies and three straight Hart Memorial Trophies, but he separated himself because he changed the essential nature of his game as radically as any athlete not named Babe Ruth. He opened up the ice, going hard to places that no defenseman had ventured. He would not merely start the attack. At times he was the attack, an adventurer with speed, skill, vision, precision and toughness. (That fight with Hadfield was Orrs first of 42 in the NHL, including playoffs.) Orr reinvented hockey by becoming the first player to lead from the back.

Could the 15-year-old sitting among the gallery gods, watching Orr work quick give-and-gos with Johnny Bucyk, actually have been right in his snap and callow judgment of Orrs place atop the pantheon? The argument for Orr as the supreme player is as ephemeral as No. 4 in mid-air. But this is indisputable: Orr could do everything Gretzky, Howe and Mario Lemieux could do, but they couldnt do everything he could.