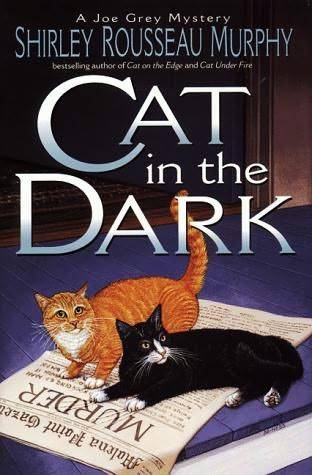

Shirley Rousseau Murphy

Cat in the Dark

The fourth book in the Joe Grey series, 1999

THE CAT crouched in darkness beneath the library desk, her tabby stripes mingled with the shadows, her green eyes flashing light, her tail switching impatiently as she watched the last patrons linger around the circulation counter. Did humans have to dawdle, wasting their time and hers? What was it about closing hour that made people so incredibly slow?

Above her the library windows were black, and out in the night the oaks' ancient branches twisted against the glass, the moon's rising light reflecting along their limbs and picking out the rooftops beyond. The time was nine-fifteen. Time to turn out the lights. Time to leave these hallowed rooms to her. Would people never leave? She was so irritated she almost shouted at them to get lost, that this was her turf now.

Beyond the table and chair legs, out past the open door, the library's front garden glowed waxen in the moonlight, the spider lilies as ghostly pale as the white reaching fingers of a dead man. Three women moved out into the garden along the stone path, beneath the oak trees' dark shelter, heading toward the street; behind them, Mavity Flowers hurried out toting her heavy book bag, her white maid's uniform as bright as moonstruck snow, her gray, wiry hair ruffled by the sea wind. Her white polyester skirt was deeply wrinkled in the rear from sitting for nearly an hour delving through the romance novels, choosing half a dozen unlikely dreams in which to lose herself. Dulcie imagined Mavity hastening home to her tiny cottage, making herself a cup of tea, getting comfy, maybe slipping into her bathrobe and putting her feet up for an evening's read-for a few hours' escape and pleasure after scrubbing and vacuuming all day in other people's houses.

Mavity was a dear friend of Dulcie's housemate; she and Wilma had known each other since elementary school, more than fifty years. Wilma was the tall one, strong and self-sufficient, while Mavity was such a small person, so wrinkled and frail-looking that people treated her as if she should be watched over-even if she did work as hard as a woman half her age. Mavity wasn't a cat lover, but she and Dulcie were friends. She always stroked Dulcie and talked to her when she stopped by Wilma's; Mavity told Dulcie she was beautiful, that her chocolate-dark stripes were as lovely as mink, that Dulcie was a very special cat.

But the little lady had no idea how special. The truth would have terrified her. The notion that Dulcie had read (and found tedious) most of the stories that she, herself, was toting home tonight, would have shaken Mavity Flowers right down to her scruffy white oxfords.

Through the open front door, Dulcie watched Mavity hurry to the corner and turn beneath the yellow glow of the streetlamp to disappear down the dark side street into a tunnel of blackness beneath a double row of densely massed eucalyptus trees. But within the library, seven patrons still lingered.

And from the media room at the back, four more dawdlers appeared, their feet scuffing along inches from Dulcie's nose- silk-clad ankles in stilted high heels, a boy's bony bare feet in leather sandals, a child's little white shoes and lace-ruffled white socks following Mama's worn loafers. And all of them as slow as cockroaches in molasses, stopping to examine the shelved books and flip through the racked magazines. Dulcie, hunching against the carpet, sighed and closed her eyes. Dawdling was a cat's prerogative, humans didn't have the talent. Only a cat could perform that slow, malingering dance, the half-in-half-out-the-door routine, with the required insolence and grace.

She was not often so rude in her assessment of human frailties. During the daytime hours, she was a model of feline amenity, endlessly obliging to the library patrons, purring for them and smiling when the old folks and children petted and fussed over her, and she truly loved them. Being official library cat was deeply rewarding. And at home with Wilma she considered herself beautifully laid-back; she and Wilma had a lovely life together. But when night fell, when the dark winds shook the oaks and pines and rattled the eucalyptus leaves, her patina of civilization gave way and the ancient wildness rose in her, primitive passions took her-and a powerful and insatiable curiosity drove her. Now, eager to get on with her own agenda, she was stifled not only by lingering humans but was put off far more by the too-watchful gaze of the head librarian.

Jingling her keys, Freda Brackett paced before the circulation desk as sour-faced as a bad-tempered possum and as impatient for people to leave as was Dulcie herself-though for far different reasons. Freda couldn't wait to be free of the books and their related routines for a few hours, while Dulcie couldn't wait to get at the thousands of volumes, as eager as a child waiting to be alone in the candy store.

Freda had held the position of head librarian for two months. During that time, she had wasted not an ounce of love on the library and its contents, on the patrons, or on anyone or anything connected with the job. But what could you expect of a political appointee?

The favorite niece of a city council member, Freda had been selected over several more desirable applicants among the library's own staff. Having come to Molena Point from a large and businesslike city library, she ran this small, cozy establishment in the same way. Her only objective was to streamline operations until the Molena Point Library functioned as coldly and impersonally as the institution she had abandoned. In just two months the woman's rigid rules had eaten away at the warm, small-village atmosphere like a rat demolishing last night's cake.

She discouraged the villagers from using the library as a meeting place, and she tried to deter any friendliness among the staff. Certainly she disapproved of librarians being friends with the patrons-an impossibility in a small town. Her rules prevented staff from performing special favors for any patron and she even disapproved of helping with book selection and research, the two main reasons for library service.

And as for Dulcie, an official library cat was an abomination. A cat on the premises was as inappropriate and unsanitary as a dog turd on Freda's supper plate.

But a political appointee didn't have to care about the job, they were in it only for the money or prestige. If they loved their work they would have excelled at it and thus been hired on their own merits. Political appointees were, in Dulcie's opinion, always bad news. Just last summer a police detective who was handed his job by the mayor created near disaster in the village when he botched a murder investigation.

Dulcie smiled, licking her whiskers.

Detective Marritt hadn't lasted long, thanks to some quick paw-work. She and Joe Grey, moving fast, had uncovered evidence so incriminating that the real killer had been indicted, and Detective Marritt had been fired-out on the street. A little feline intervention had made him look like mouse dirt.

She wished they could do the same number on Freda.

Behind the circulation desk, Dulcie's housemate, Wilma Getz, moved back and forth arranging books on the reserve shelf, her long, silver hair bound back with a turquoise clip, her white turtleneck sweater and black blazer setting off to advantage her slim, faded jeans. The two women were about the same age, but Wilma had remained lithe and fresh, while Freda looked dried-up and sharp-angled and sour-and her clothes always smelled of mothballs. Dulcie, watching the two women, did not expect what was coming.

Next page