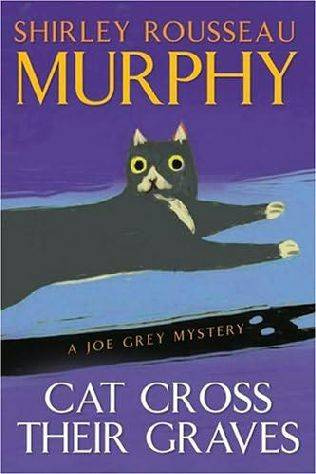

Shirley Rousseau Murphy

Cat Cross Their Graves

The tenth book in the Joe Grey series, 2005

I do not know that I ever saw anything more terrible than the struggle of that Ghost against joy. For he had almost been overcome. Somewhere, incalculable ages ago, there must have been gleams of humour and reason in him But [now] the light that reached him, reached him against his will he would not accept it.

C. S. Lewis, The Great Divorce

Up the Molena Point hills where the village cottages stood crowded together, and their back gardens ended abruptly at the lip of the wild canyon, a row of graves lay hidden. Concealed beneath tangled weeds and sprawling overgrown geraniums, there was no stone to mark the bodies. No one to remember they were there save one villager, who kept an uneasy silence. Who nursed a vigil of dread against the day the earth would again be disturbed and the truth revealed. On winter evenings the shadow of the tall, old house struck down across the graves like a long black arrow, and from the canyon below, errant winds sang to the small, dead children.

There had been no reports for a dozen years of unexplained disappearances along the central California coast, not even of some little kid straying off to turn up at suppertime hungry and dirty and unharmed. Nor did the three cats who hunted these gardens know what lay beneath their hurrying paws. Though as they trotted down into the canyon to slaughter wood rats, leaping across the tangled flower beds, sometimes tabby Dulcie would pause to look around her, puzzled, her skin rippling with an icy chill. And once the tortoiseshell kit stopped stone still as she crossed the neglected flower bed, her yellow eyes growing huge. She muttered about a shadow swiftly vanishing, a child with flaxen hair. But this kit was given to fancies. Joe Grey had glanced at her, annoyed. The gray tom was quite aware that female cats were full of wild notions, particularly the tattercoat kit and her flights of fancy.

For many years the graves had remained hidden, the bodies abandoned and alone, and thus they waited undiscovered on this chill February night. The village of Molena Point was awash with icy, sloughing rain and shaken by winds that whipped off the surging sea to rattle the oak trees and scour the village rooftops. But beneath the heavy oaks and the solid shingles and thick clay tiles, within scattered cottages, sitting rooms were warm, lamps glowed and hearth fires burned, and all was safe and right. But many cottages stood dark. For despite the storm, it seemed half the village had ventured out, to crowd into Molena Point Little Theater for the week-long Patty Rose Film Festival. There, though the stage was empty, the darkened theater was filled to capacity. Though no footlights shone and there was no painted backdrop to describe some enchanted world and no live actors to beguile the audience, not a seat was vacant.

Before the silent crowd, the silver screen had been lowered into place from the high, dark ceiling, and on it a classic film rolled, a black-and-white musical romance from a simpler, kinder era. Old love songs filled the hall, and old memories for those who had endured the painful years of World War II, when Patty's films had offered welcome escape from the disruptions of young lives, from the wrenching partings of lovers.

For six nights, Molena Point Little Theater audiences had been transported, by Hollywood's magic, back to that gentler time before X-ratings were necessary and audiences had to sit through too much carnage, too much hate, and the obligatory bedroom scene. The Patty Rose Film Festival had drawn all the village back into that bright world when their own Patty was young and vibrant and beautiful, riding the crest of her stardom.

Every showing was sold out and many seats had been sold again at scalpers' prices. On opening night Patty herself, now eighty-some, had appeared to welcome her friends; it was a small village, close and in many ways an extended family. Patty Rose was family; the blond actress was still as slim and charming as when her photographs graced every marquee and magazine in the country. She still wore her golden hair bobbed, in the style famous during those years, even if the color was added; her tilted nose and delighted smile still enthralled her fans. To her friends, she was still as beautiful.

When Patty retired from the screen at age fifty and moved to Molena Point, she could have secluded herself as many stars do, perhaps on a large acreage up in Molena Valley where a celebrity could retain her privacy. She had, instead, bought Otter Pine Inn, in the heart of the village, and moved into one of its third-floor penthouses, had gone quietly about her everyday business until people quit gawking and sensibly refrained from asking for autographs. She loved the village; she walked the beach, she mingled at the coffee shop, she played with the village dogs. She soon headed up charity causes, ran benefits, gave generously of her time and her money.

Two years ago she had bought an old historic mansion in need of repair, had fixed it up and turned it into a home for orphaned children. "Orphans' home" was an outdated term but Patty liked it and used it. The children were happy, they were clean and healthy, they were well fed and well educated. Eighty-two percent of the children went on to graduate from college. Patty's friends understood that the home helped, a little bit, to fill the dark irreparable void left by the death of Patty's daughter and grandson. Between her civic projects and the children's home, and running the inn, Patty left herself little time for grieving.

She took deep pleasure in making the inn hospitable. Otter Pine Inn was famous for its cuisine, for its handsome and comfortable accommodations, and for the friendly pampering of its guests. It was famous indeed for the care that Patty extended to travelers' pets. There are not so many hotels across the nation where one's cats and dogs are welcome. Otter Pine Inn offered each animal velvet cushions by a window, a special menu of meaty treats, and free access to the inn's dining patio when accompanied by a human. Sculptures of cats and dogs graced the patio gardens, and Charlie Harper's animal drawings hung in the inn's tearoom and restaurant. Police captain Max Harper had been Patty's friend from the time she arrived in Molena Point, long before he met and married Charlie.

When Patty first saw Charlie's animal drawings, she swore that Charlie made some of her cats seem almost human, made them look as if they could speak. Patty Rose was perceptive in her observations, but in the matter of the three cats who lived with three of her good friends, Patty had no idea of the real truth. As for the cats, Joe Grey and Kit and Dulcie kept their own counsel.

Now in the darkened theater, as the last teary scenes drew to a close, Charlie leaned against Max's shoulder, blowing her nose. On her other side, Ryan Flannery reached for a tissue from the box the two women had tucked between them. Patty's films might be musicals, but the love interest provided enough cliff-hanging anxiety to bring every woman in the audience to tears. Over Charlie's bright-red hair and Ryan's dark, short bob, Max Harper glanced across at Clyde with that amused, tolerant look that only two males can share. Women-they always cried at a romantic movie, squeezed out the tears like water from a sponge. Charlie cut Max a look and wiped her tears; but as she wept at the final scenes, she looked up suddenly and paused, and her tears were forgotten. A chill touched Charlie, a tremor of fear. She stared up at the screen, at Patty, and a fascination of horror slid through her, an icy tremor that held her still and afraid, a rush of fear that came out of nowhere, so powerfully that she trembled and squeezed Max's hand. He looked down at her, frowning, and drew her close. "What?"

Next page