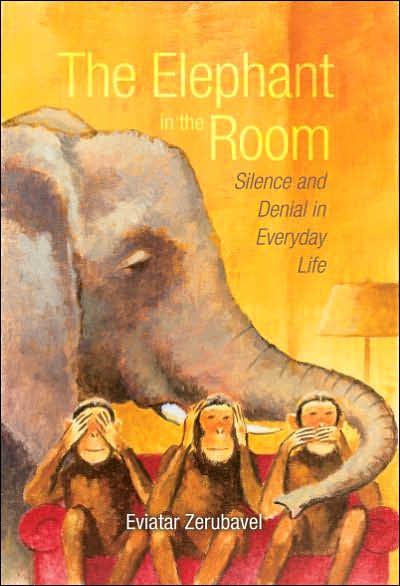

The Elephant in the Room

This page intentionally left blank

The Elephant

in the Room

Silence and Denial

in Everyday Life

Eviatar Zerubavel

2006

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that

further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright 2006 by Eviatar Zerubavel

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zerubavel, Eviatar.

The elephant in the room : silence and denial in everyday life /

Eviatar Zerubavel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-518717-5

ISBN-10: 0-19-518717-2

1. Denial (Psychology)Social aspects.

2. Avoidance (Psychology)Social aspects.

3. Silence. 4. Secrecy. 5. Social psychology.

I. Title.

HM1041.Z47 2006

302.2dc22 2005023273

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

To Noam,

whose courage to see, hear, and speak I admire

This page intentionally left blank

Contents

vii

viii

Preface

Contents

Preface

ix

T he seeds of this book date back to my childhood. Growing up in a home where every single room housed some unmentionable elephant, I was always surrounded by open secrets that, although widely known, nevertheless remained unspoken. Similarly significant in this regard was the experience of growing up in the 1950s in Tel Aviv, where most of what remained from the pre-1948 non-Jewish past of some of its neighborhoods were their Arab names. Witnessing years later the tremendous pain suffered by individuals who try to resist collective efforts to quash elephants through forced silence further triggered my interest in the nuanced tension between what is personally experienced and what is publicly acknowledged.

Yet it was a particular experience I had as a director of a doctoral program that ultimately inspired me to write this book. In the spring of 1998 I found myself in a situation of having to deal with a most disturbing series of events that threatened the social and moral fabric of my department yet that, for an un-usual combination of reasons involving both fear and shame, although widely known and insidiously pervasive, were nevertheless publicly ignored by many of my colleagues. Like the ix

x

Preface

situation itself, I found their response to it personally distress-ing yet at the same time intellectually fascinating. Having written about the social aspects of the process of noticing, I became increasingly interested in the social aspects of the process of ignoring. I was also becoming increasingly aware of the highly problematic long-term impact of silence on individuals as well as on entire groups.

The following year I presented an early overview of my evolving ideas about the social organization of silence and denial at a national conference hosted by my department. My talk generated a lot of discussion, yet of the dozen or so of my colleagues who attended only two mentioned it to me later, which exemplified my argument about our general reluctance to openly talk about not talking. Three years later, in November 2002, I started to write this book.

In her memoir After Silence: Rape and My Journey Back , Nancy Raine describes how difficult it is to write about silence, since the very act of writing often evokes precisely the painful themes about which one is writing. And indeed, although this is the ninth book I have written, none of the others was so difficult for me to write. Spending entire days writing and rewriting sentences that were evidently far too evocative for me, I suddenly understood for the first time why the Hebrew words for silence and paralysis are actually derived from the same root. While writing about silence, therefore, talking with others can become a cherished necessity, and I am particularly grateful in this regard to Kathy Gerson, Debby Carr, Jenna Howard, Ruth

Simpson, Ira Cohen, Allan Horwitz, Ethel Brooks, Miriam

Bauer, Dan Ryan, Karen Cerulo, Ellen Idler, Carolyn Williams, and Suzanne Zatkowsky for helping me avoid becoming totally engulfed by the overwhelming, painful silence surrounding me.

Yael Zerubavel, Ruth Simpson, Debby Carr, Tom DeGloma,

Dan Ryan, Chris Nippert-Eng, Kathy Gerson, Jenna Howard, Preface

xi

Arlie Hochschild, Lynn Chancer, Allan Horwitz, Samantha

Spitzer, Kari Norgaard, Johanna Foster, and Wayne Brekhus were kind enough to read early drafts of the manuscript and offer many helpful suggestions for improvement. I also benefited tremendously from discussing my evolving ideas with my children Noga and Noam Zerubavel as well as with Kristen Purcell, Anat Helman, Kathryn Harrison, Carolyn Barber,

Viviana Zelizer, Robin Wagner-Pacifici, Jan Lewis, Doug

Mitchell, Frances Milliken, Ann Mische, and Zali Gurevitch. I would also like to thank my editor, Tim Bartlett, for helping me present those ideas in a way that would make them more accessible to a wider audience, as well as the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, whose 2003 fellowship,

generously complemented by Rutgers University, allowed me to take a year off during which I could fully dedicate myself to writing it. Thanks are also due to Paula Cooper for a terrific job of editing the manuscript.

Finally, a special thank-you to my wife, companion, and life-long friend Yael Zerubavel, who was with me throughout this long, arduous journey. Thank you for your nonsilent understanding and support.

East Brunswick, New Jersey

June 2005

We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Letter From Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963

The Elephant in the Room

This page intentionally left blank

Although I know Aunt Lace knew about the rapeand, of course, she knew I knew my mother had told herwe never mentioned it. I never brought it up, nor did she.

Nancy Raine, After Silence

T here is a famous fourteenth-century Castilian story about a Moorish king duped by three swindlers into believing

that a dazzling new suit they are supposedly weaving for him is somehow invisible to any person of illegitimate birth. Embarrassed to admit he cannot see the glamorous fabric, a servant sent to inspect their work reports that good progress is being made. A second servant soon comes back and corroborates this account. The king then goes to see the fabric for himself. Fear-ing that if he were to admit he cannot actually see anything he might lose his legitimacy and consequently his kingdom, he 1

The Elephant in the Room

proceeds to praise the invisible cloth lavishly. This then leads a constable, obviously concerned about his own reputation, also to extol it, which understandably makes the king even more embarrassed that he cannot see it.

Next page