The author and publishers would like to thank the Tony Benn Archives for permission to use the above photographs.

B y the early twenty-first century few people could remember a time when Tony Benn was not playing a leading role in politics. Only the Queen had been longer in public life and was still active in 2011. Benn served fifty years in the House of Commons, having been elected sixteen times, more than any other parliamentarian.

He spent eleven years as a minister of cabinet rank and was for more than thirty years on Labours National Executive Committee. These facts alone give him a remarkable record of service, but Benn has also been responsible for more constitutional change in Britain than any other politician excepting some of those who became Prime Minister. His successful battle to renounce his peerage represented a fundamental statement about the relationship between the Lords and the Commons and the primacy of elected authority. His campaign for a referendum on membership of the Common Market meant a constitutional door was opened which can never again be closed. The reforms he supported in the Labour Party for re-selection of MPs and a wider franchise for the election of the party leader have had far-reaching effects in other parties and other organisations. Equally penetrating has been his questioning of the nature of political power in Britain, his criticism of the way the power of the crown is concentrated in the hands of the Prime Minister and appointed officials, bypassing the Commons.

Yet he is widely seen as a failure as a politician, someone who almost became leader of the Labour Party. In the late 1960s he was not only tipped for the leadership within a decade, there seemed to be no one else in the race. However his enemies tried to marginalise him, he was always back with his quick wit and his moral superiority. Yet he stood for the leadership twice and twice, equally unsuccessfully, for the deputy leadership. Despite his acknowledged political skill, the positions he adopted made him unacceptable to his colleagues. Some would say Benn simply backed the wrong horse in leading the left wing in the 1970s, and that he mistakenly believed it was a winning strategy. This biography challenges that view, showing that in the context of the rest of his life his move to the left was not a sudden leap but a natural working out of ideas. It was also in the tradition of the best role model he had: his father.

The Labour MPs would not back him as a socialist in the 1970s and 1980s; but neither did his parliamentary colleagues give their fulsome support in the preceding two decades. The underlying fact is that the Labour Party is a conservative party which is rather more efficient in undermining radicalism in its own ranks than in political combat with the Tories.

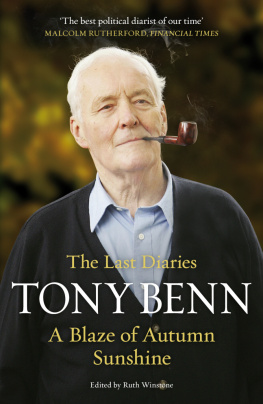

This biography offers an understanding of what makes this enigmatic man interesting as a politician, of his strengths and his weaknesses. It attempts an all round survey of the man, for the controversy surrounding his political stance has unfairly diverted attention from a full appreciation of his talents. He is one of the greatest orators of the second half of the century admittedly a period in which the art of oratory was in decline. He has written the most extensive published political diary of his times. He has also kept what are probably the best records of any politician. This book relies heavily on material from the Benn Archives and I am deeply indebted to Tony Benn for permitting me access. I am also indebted to the Benn family for tolerating me with such good humour. Likewise Tony Benns staff. His secretary Kathy Ludbrook also gave me the benefit of her extensive knowledge of the Labour Party.

There can be few editors who have had every piece of their work traced back to source as Ruth Winstone has, with my going through the unedited volumes of the Benn Diaries in her office. This she bore with equanimity, and despite my attempts to catch her out on errors of detail, I was never successful. She also gave patient advice at every stage of my work, initially over a three year period, which extended (with republication and updating of this book) to twenty-three years. Tony Benn himself was generous with his time, allowing me fifteen lengthy interviews. He described them as a bit like the day of judgement without actually dying.

Many of the people who were good enough to consent to be interviewed are mentioned in the references. Sometimes former colleagues of Tony Benn were prepared to see me at some discomfort to themselves. Meeting people in hospital rooms or talking to those who were clearly in the final stages of illness made me feel as if I were plucking history from the very jaws of death.

All errors and omissions are my responsibility, but the following people have been so kind as to read the manuscript, or large parts of it, and make comments: Andrew Adams, David Benn, David Butler, Richard Coopey, Harold Hewitt and Michael Zander.

Finally, but most importantly, my profound thanks to Julie Peakman, for her practical and moral support while I was working on this book. November 1991

In updating this book to incorporate the twenty years of Tony Benns life since its first publication, I am indebted to Sam Carter of Biteback and to my agent Diana Tyler of MBA Literary Agents for their persistence and belief in the project. March 2011

When I was born in 1925, Tony Benn reflected while in his sixties, twenty per cent of the world was ruled from London. In my lifetime I have seen Britain become an outpost of America administered from Brussels.

T he young Benn was able to observe Britains changing role in world affairs from the vantage point of an intensely political home. His first coherent political memory is of visiting Oswald Mosley, then a Labour MP, at his home in Smith Square. He remembers thanking Mosley for his hospitality in what he has described as his first speech. When he was five in 1930 he went to see the Trooping of the Colour from the back of 10 Downing Street. He was more impressed with the chocolate biscuits than with meeting Ramsay MacDonald, the Prime Minister. A deeper impression was made by the gentle yet strangely dressed figure of Gandhi, in London in 1931 for the second Round Table Conference, which Benns father had convened when Secretary of State for India.

What made a lasting impression on Benn was the knowledge that the powerful talked, walked and ate like everyone else, lived in houses just like him, were accessible. Schoolmates later talked of his self-assurance, of his confidence in his own position. He could respect the mighty as people but he had learned as automatically as he learned to speak that they were just other folk doing a job. When he was later to challenge prime ministers and sit with the Queen discussing stamps he was not tongue-tied. Inoculated by minute exposure from an early age, he had developed an immunity to awe.

Tony Benn was the second son of William Wedgwood Benn and Margaret Benn, later Viscount and Lady Stansgate. He was named Anthony because Sir Ernest Benn, his uncle, had bought a painting depicting a Sir Anthony Benn who had been a courtier in Elizabethan Ernest Benn left the portrait to his nephew in his will but sold it when Tony Benn joined the Labour Party on his seventeenth birthday. The picture re-entered the family when the new owner sold it to Tony Benns wife Caroline.

Baby Anthony received as his second name Neil, because his mother wanted to remind him of his Scottish ancestry. The name Wedgwood is a direct reference to his father. William Wedgwood Benn had been so christened in 1877 because his maternal grandmother, Eliza Sparrow, was a distant cousin of the pottery family. Tony Benns debt to his father is clear from a tribute he wrote in 1977, His inherited distrust of established authority and the conventional wisdom of the powerful, his passion for freedom of conscience and his belief in liberty, explain all the causes he took up during his life, beginning with his strong opposition to the Boer War as a student, at University College, London, for which he was, on one occasion, thrown out of a ground-floor window by patriotic contemporaries.