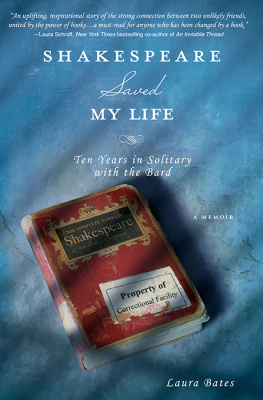

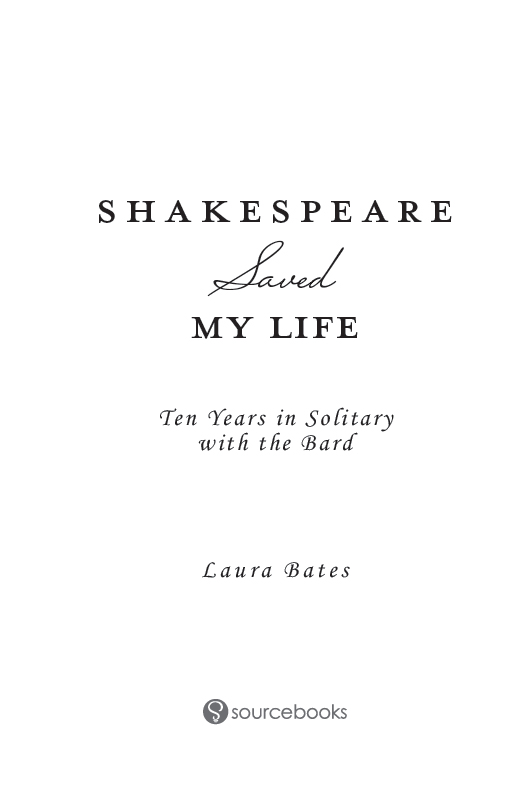

Copyright 2013 by Laura Bates

Cover and internal design 2013 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Vivian Ducas

Cover illustration by Shane Rebenschied

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

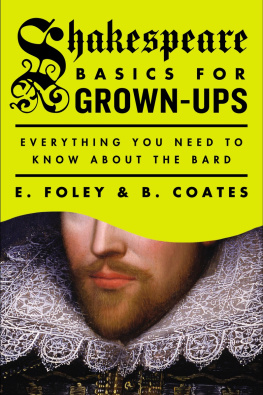

From Bates, L. To Know My Deed: Finding Salvation through Shakespeare. In Performing New Lives: Prison Theater, edited by J. Shailor, 3348. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2011. Reprinted with permission of Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

This book is a memoir. It reflects the authors present recollections of her experiences over a period of years. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

www.sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a book about a prisoner in solitary confinement

and how his life was changed by Shakespeare.

It is also about a Shakespeare professor

and how her life was changed by the prisoner.

Welcome to a world that few ever enter,

a world in which both prisoner and professor spent ten years together,

learning, sharing, and growing through Shakespeare.

Ive been down this week.

I was thinking maybe Im a little homesick.

Home. To me, I think its more an ideal than a place.

Around the people you love, thats home, thats what excites me the most.

The possibility of enjoying some of my life with the people I love.

Cause it goes quick, dont it?

Life. Dont it go?

I mean, Im only thirty. Im not old.

But, you know, Ive been in here since I was a kid.

It just goes so fast. Man! It just goes so fast.

And everybody overlooks enjoying it.

They just put themselves into so many prisons.

Larry Newton

Contents

Foreword

The work that Laura Bates has been doing for years with prison inmates and Shakespeare is of extraordinary importance. It has a kind of beauty and symmetry all its own.

I have had the remarkable experience of being with her in small group discussions, first at Chicagos Cook County Jail in 1996 and more recently with her inmate students in the correctional facilities of the state of Indiana, most notably the maximum-security Wabash Valley. Few experiences are as lastingly and vividly etched on my consciousness.

At the Chicago lockup, security guards ushered me through at least four heavily locked gates that clanged shut as I passed through them. I then found myself in a sizable, windowless room with Laura as teacher and some eight or nine prison inmates, all of them African Americans in the age range of twenty to thirty-five and guilty of violent crimes including homicide as students. But no armed guards were present. The business of the day was to work on what one might call the rumble scene, right at the center of Romeo and Juliet, when first Mercutio and then Tybalt are slain in street fighting. Laura took her students through the scene, word by word, making sure that everyone understood what was being said. This led to a discussion of the ethics of gang warfare, hearkening back to the opening scene of the play with its violent confrontation of Capulets versus Montagues. Who started the brawl in act 3, scene 1? Who or what was to blame for the ancient quarrel between the two families? Why does Mercutio challenge Tybalt to a fight? What are we to make of the gentle words Romeo has for Tybalt when Romeo has been openly insulted by his opposite number? What do Romeos friends make of his calm, dishonorable, vile submission? Is Romeo to blame for changing his mind after the death of Mercutio? To what extent are peer pressures responsible for his decision to fight Tybalt? On all these matters, the student inmates called on their own extensive experience with gang rivalries and machismo codes of male honor. Everything they said seemed beautifully appropriate to me.

Then Laura had them stand up and speak their lines as dialogue. They did quite well, even if the proper names came across as strange: Tybalt, Mercutio, Capulet, and Montague. Lauras next move was wonderful, I thought: she asked them to paraphrase what the lines said in their own habits of speech. Hey, man, lets get out of here, said Benvolio to Mercutio. Its hot, man, and those dudes the Capulets will be here any minute and theres going to be trouble. You have about as much courage as a sick chicken, said Mercutio in reply. If you dont have a couple of drinks in you, your face turns as white as my shirt. And so it went, with greater and lesser degrees of accuracy. Laura was cool. She was in charge. She didnt stand for any nonsense, but she listened, she helped, she respected. The men were plainly willing to be doing what they were doing. A gutsy performance on all sides.

Years later, I visited Laura at Indiana State University, where I had the stirring experience of talking with some of Lauras student inmates in the Indiana correctional system. They asked good questions. They talked with one another. The subject at hand was Macbeth. Even gutsier than her Romeo and Juliet work in Chicago is her work with Macbeth in solitary confinement.

Recently, I copresented with Laura at a Shakespeare conference, where she showed a documentary of her work at the Wabash Valley Correctional Facility. Here the prisoners were not only inmates of Indianas maximum-security prison, but they were also in solitary confinement because they were judged to be especially violent and thus dangerous to guards and other inmates alike. They were in individual cells, each with a small aperture at waist height designed to facilitate the passing into the cell of food or whatever. Their voices could be heard, and their faces were partly visible when they crouched down at the aperture. They were escorted from their cells one at a time with two armed guards. No other person was allowed in the corridor when a prisoner was released into that space. Here it was that Laura sat on an improvised chair, asking questions, leading a discussion about Macbeths decision to kill Banquo. It is terrific that these prisoners have a chance to read and think about Macbeth, because what hangs over the play so much is the sense of fallen human nature and the threat of temptation that even an honorable man cannot resist: there but for the grace of God go I.

The most remarkable of all the inmates whom Ive gotten to know through Laura at the Wabash Valley Correctional Facility is Larry Newton, the subject of this fine book. Laura set up an interview between Larry and me one day. I was impressed at once with Larry: a serious person, gracious, good-humored, alive with intellectual curiosity. Laura suggested to Larry that he start things off by asking me questions that were on his mind.

Larry asked me, Do you think that Shakespeare wrote King John after the death of his own child? The pain he describes just seems so real.

To say the least, this question took me entirely by surprise.

Next page