3

EDEN

Now the LORD had said vnto Abram, Get thee out of thy countrey, and from thy kinred, and from thy fathers house, vnto a land that I will shew thee.

And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will blesse thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt bee a blessing.

G ENESIS , XII:12

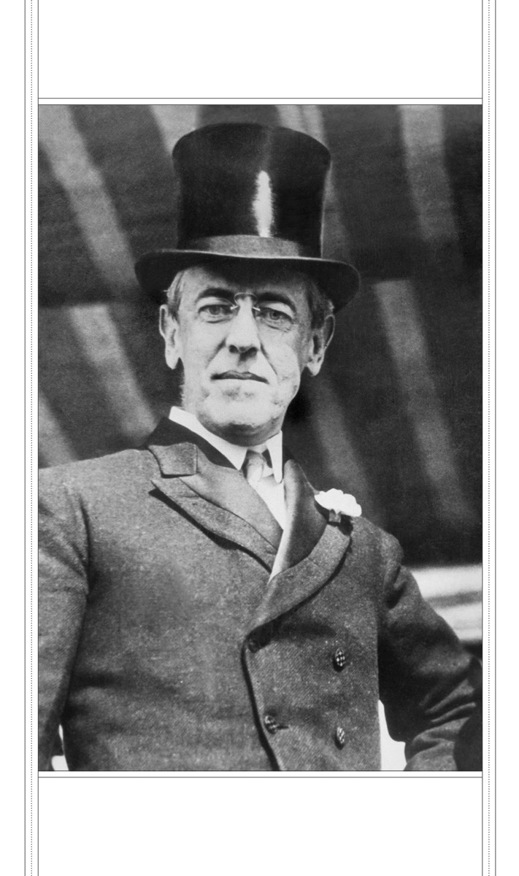

A t the end of a spur track of the Pennsylvania Railroad line, eighteen-year-old freshman Thomas Woodrow Wilson stepped off the dinky train at the little station in Princeton. In few other places within the thirty-seven reunited states did so much educational, political, and religious history converge as they did in this town of three thousand people in the middle of New Jersey.

The first seeds of higher education in the United States had, in fact, been planted elsewhere centuries earlieronly sixteen years after the Pilgrims disembarked the Mayflower. In 1636, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony authorized the founding of what became Harvard College. Almost six decades later, a second collegeWilliam and Marywas founded as an Anglican institution in Virginia; and eight years after that, in 1701, the General Court of the Colony of Connecticut permitted ten Congregationalist clerics to organize a college to train ministers, naming it after its primary benefactor, Elihu Yale.

In 1718 the Reverend William Tennent, a Scottish-educated Ulsterman, immigrated to the middle colonies, where he and his sons helped ignite what became known as the Great Awakening, an evangelical movement that started in the Congregationalist churches of New England and ran the length of the Appalachians to the Presbyterian churches in the South. On October 22, 1746, Governor John Hamilton issued a charter for the College of New Jersey. While its founders included several of Tennents disciples who hoped to prepare ministers of the Gospel, they believed equally in educating young men of various religious persuasions for other professions.

One hundred fifty years later, Professor Woodrow Wilson would praise those divines, for they acted without ecclesiastical authority, as if under obligation to society rather than to the church. They were acting as citizens, not as clergymen, and the charter they obtained said never a word about creed or doctrine. They selected the Reverend Jonathan Dickinson to serve as the schools first president in his parsonage in Elizabeth. He died within a year, leaving his student body of ten pupils to his successor, the Reverend Aaron Burr, Sr., who moved the college to his parish in Newark. He established entrance criteria and a curriculum; and, in his tenth year in office, he provided his most enduring contribution.

Burr moved the enterprise to Princetonthen a forty-house village halfway between New York City and Philadelphia. Its position on a low ridge of fertile farmland that close to two of the most thriving cities in the Colonies promised academic seclusion and cultural access. Nathaniel FitzRandolph, the son of an original Quaker settler in the area, donated four and a half acres and twenty New Jersey pounds. He passed the hat among his neighbors, while Burr solicited funds from donors who might contribute enough to construct a grand edifice that would serve as the entire college for several years to come. They chose local Stockton sandstone, ochre in color and faintly iridescent. When the building was completed two years later, the trustees wished to name it in honor of the Governor, Jonathan Belcher; but he generously declinedsparing future generations incalculable sophomoric ridiculeand suggested they honor the late King William III, the Prince of Orange, a member of the House of Orange-Nassau.

For years, Nassau Hall reigned as the largest building in the Colonies. Set back from the main street of the town, behind a low iron gate, the building was almost two hundred feet long and fifty feet deep, with a central transept-like projection that added four feet in the front and twelve in the back. A row of windows spanned the length of each of the three floors, with the tops of the basement windows poking their heads just above ground. There were ninety-four of them at the front of the building alone. The exterior walls were more than two feet thick. With its forty-two rooms, Nassau Hall could house a library (mostly Governor Belchers five hundred books) as well as dormitories and classrooms for as many as 150 students and faculty members and an office for the president; the basement contained the kitchen and refectory. The buildings primary feature was the two-story prayer hall that projected from the rear. Not long after the building opened, students discovered the virtues of its long corridors for bowling. Perched atop the hipped roof was a cupola, which housed a large bell that rang at five oclock in the morning, summoning the students to morning prayers, and throughout the day signaling periods of study, meals, and prayer.

Within a year of taking occupancy, Burr died at forty-one. His wife died less than a year later, orphaning their two young childrenincluding Aaron Burr, Jr., the future Founding Father who turned treasonous. Fortunately, the trustees had been able to impress upon Burrs father-in-law the presidency of the college. And so, in January 1758, Jonathan Edwards, Americas foremost theologianwhose sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God epitomized the First Great Awakeningmoved from Massachusetts to become the new master of Nassau Hall. That March he received an inoculation for smallpox, from which he succumbed. The untimely deaths of his next two successors did not demoralize the college trustees. In fact, they raised their sights and turned to one of Scotlands most eminent scholars and preachers.

Educated at the University of Edinburgh and ordained by the Church of Scotland, John Witherspoon, then in his mid-forties, was an activist evangelical within the Kirkwho had expressed no desire to leave his homeland. Providentially, two persuasive alumni of the College of New Jersey were in Britain that year, and they convinced him and his wife to pack up their five children and venture overseas for a more primitive life and an even more challenging opportunity. To commemorate the night of their arrival in Princeton in 1768, the students lit a candle in each of Nassau Halls windows.

Witherspoon found a college not living up to its potentialwhat with an ill-prepared student body and insufficient funds. The preacher in him unabashedly solicited money beyond the confines of the town, and the educator within pushed the curriculum beyond the strictly classical and Christian. He recruited a professor to teach mathematics and natural philosophy and another to teach divinity and moral philosophy. And nobody taught more than Witherspoon himself. He lectured upon taste and style as well as upon abstract questions of philosophy, and upon politics as a science of government and of public duty as little to be forgotten as religion itself in any well considered plan of life, Wilson would note. Combining his personal library of three hundred books with that of the college, Witherspoon enabled students to sample contemporary politics and literature. He also delighted in the green space surrounding Nassau Hall and its neighboring buildings and contributed to the English language a new word for the college grounds, from the Latin for fieldcampus.

It was a piece of providential good fortune that brought such a man to Princeton at such a time, Wilson added. The blood of John Knox ran in Witherspoons veins. The great drift and movement of English liberty from Magna Charta down was in all his teachings. He became one of New Jerseys signers of the Declaration of Independencethe only clergyman among the fifty-six delegates.