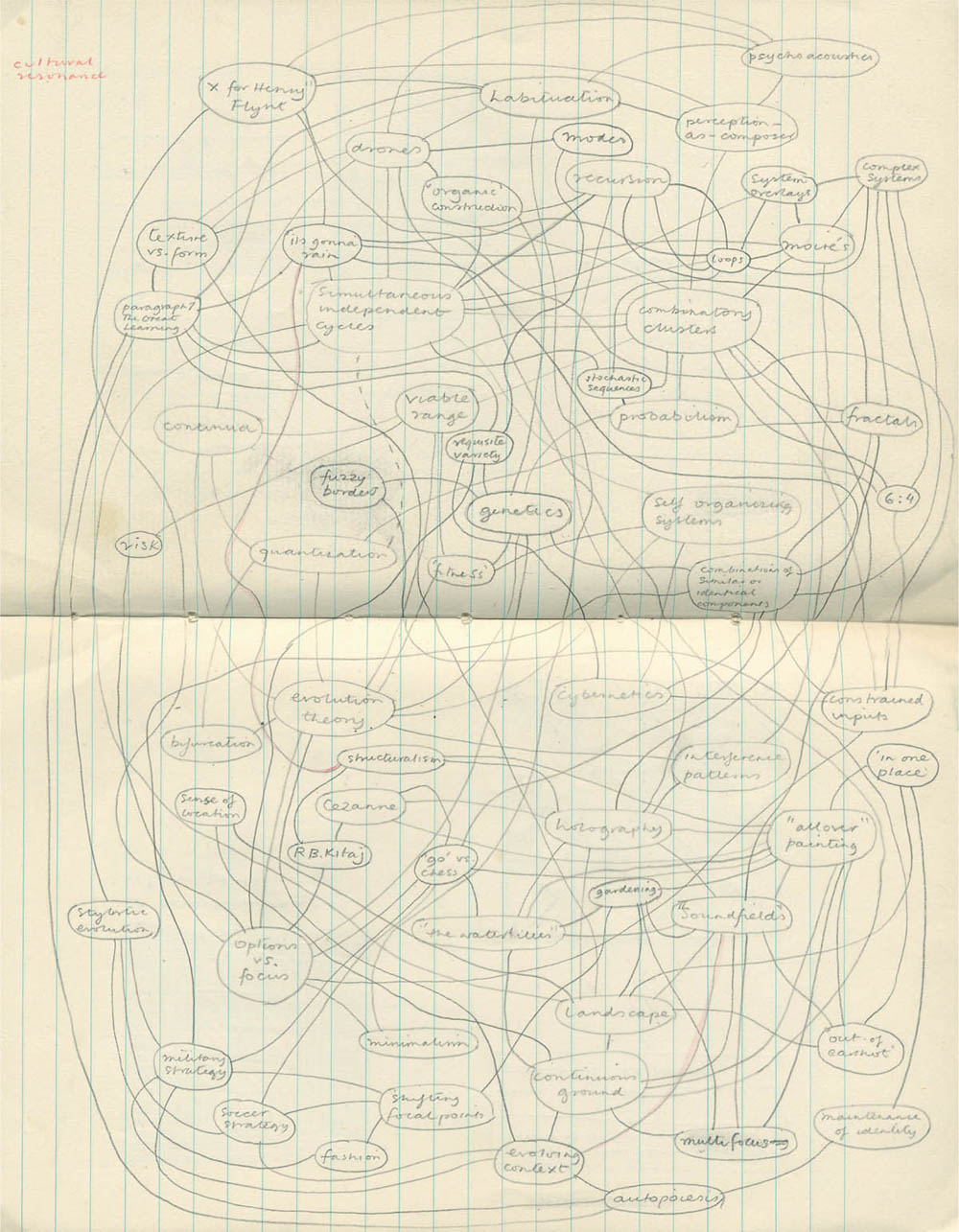

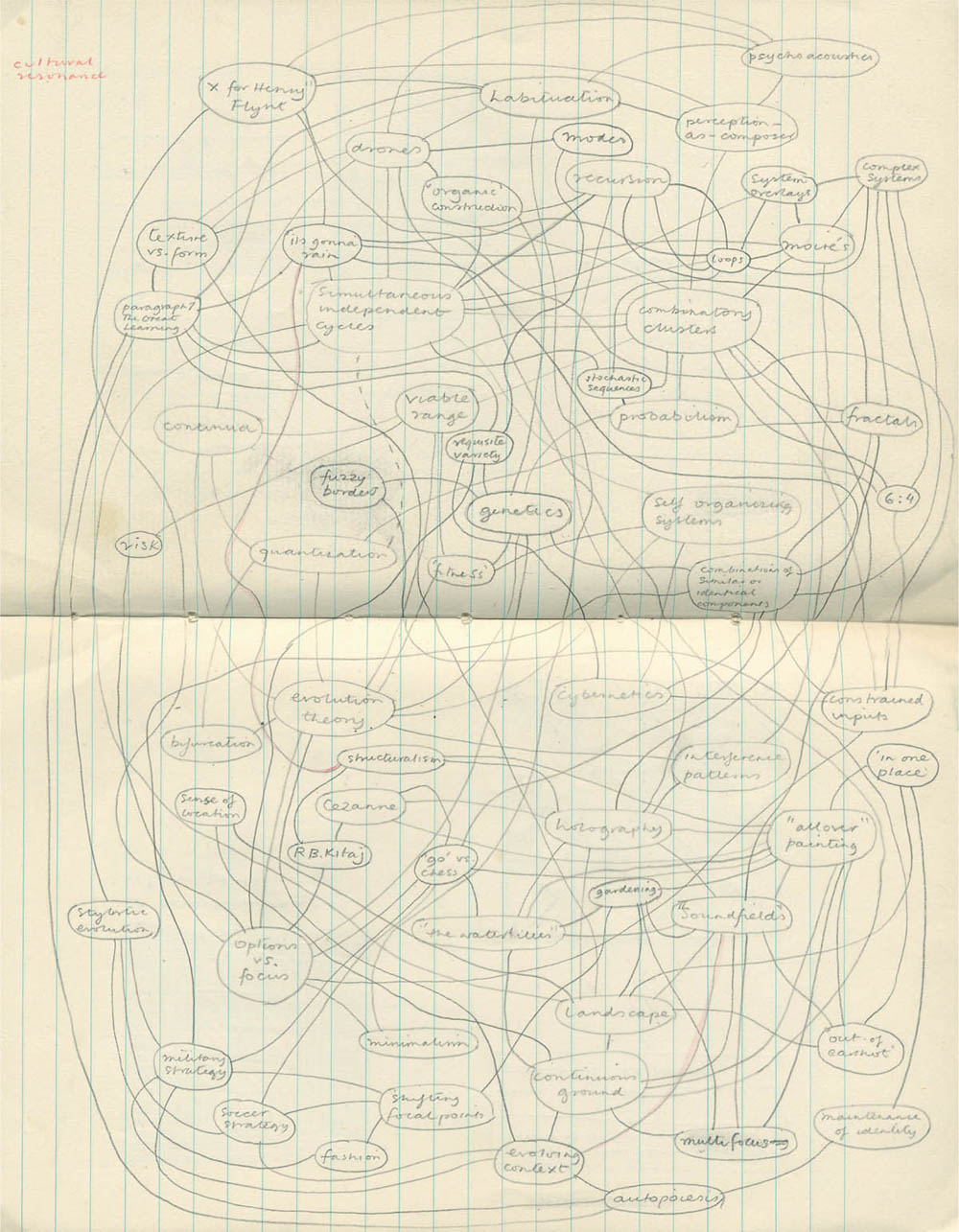

Page from one of Enos notebooks, 198485.

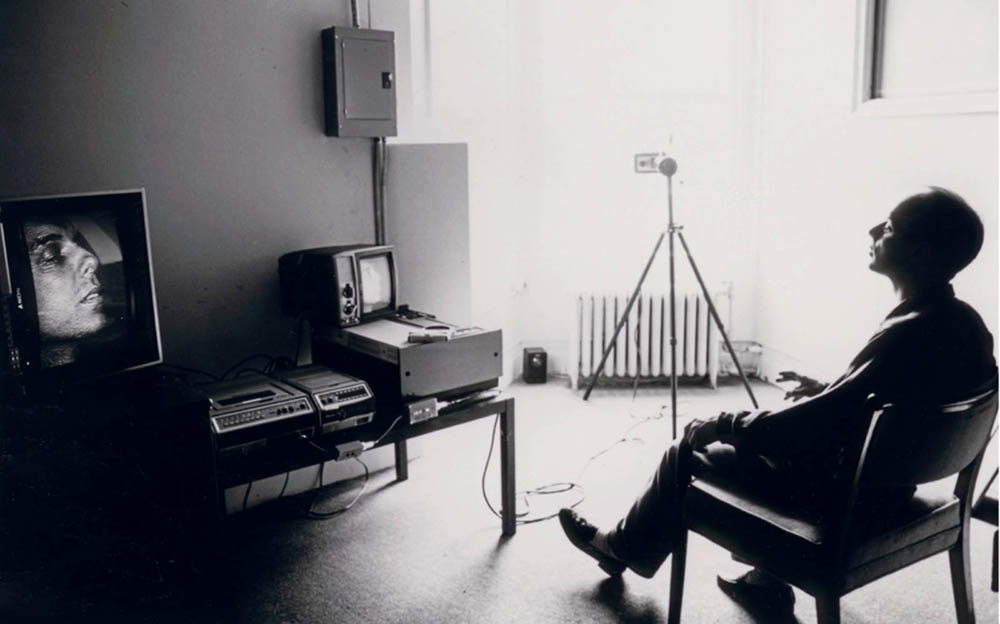

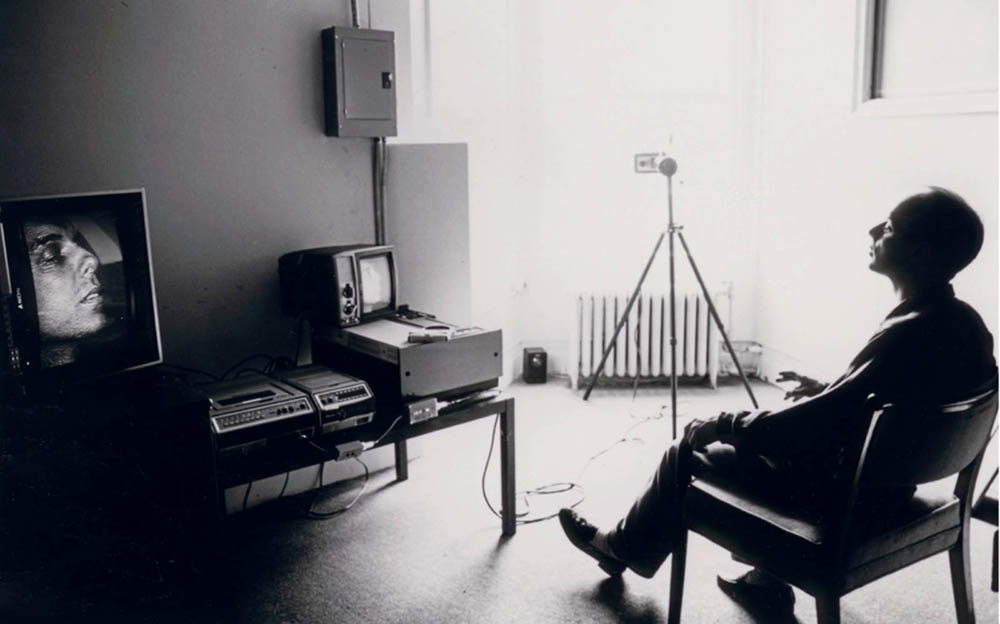

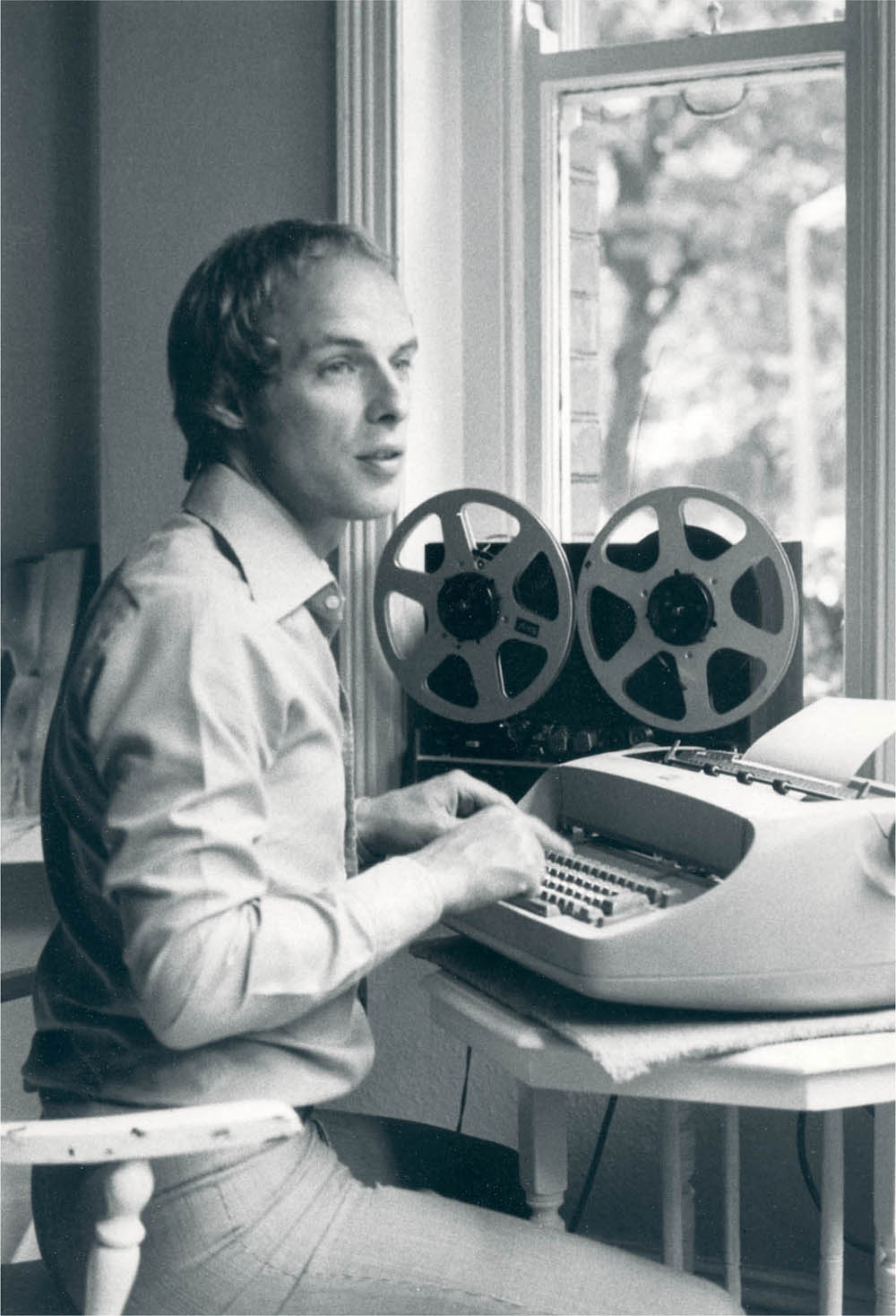

Eno experimenting with video equipment in his New York City apartment, late 1970searly 1980s.

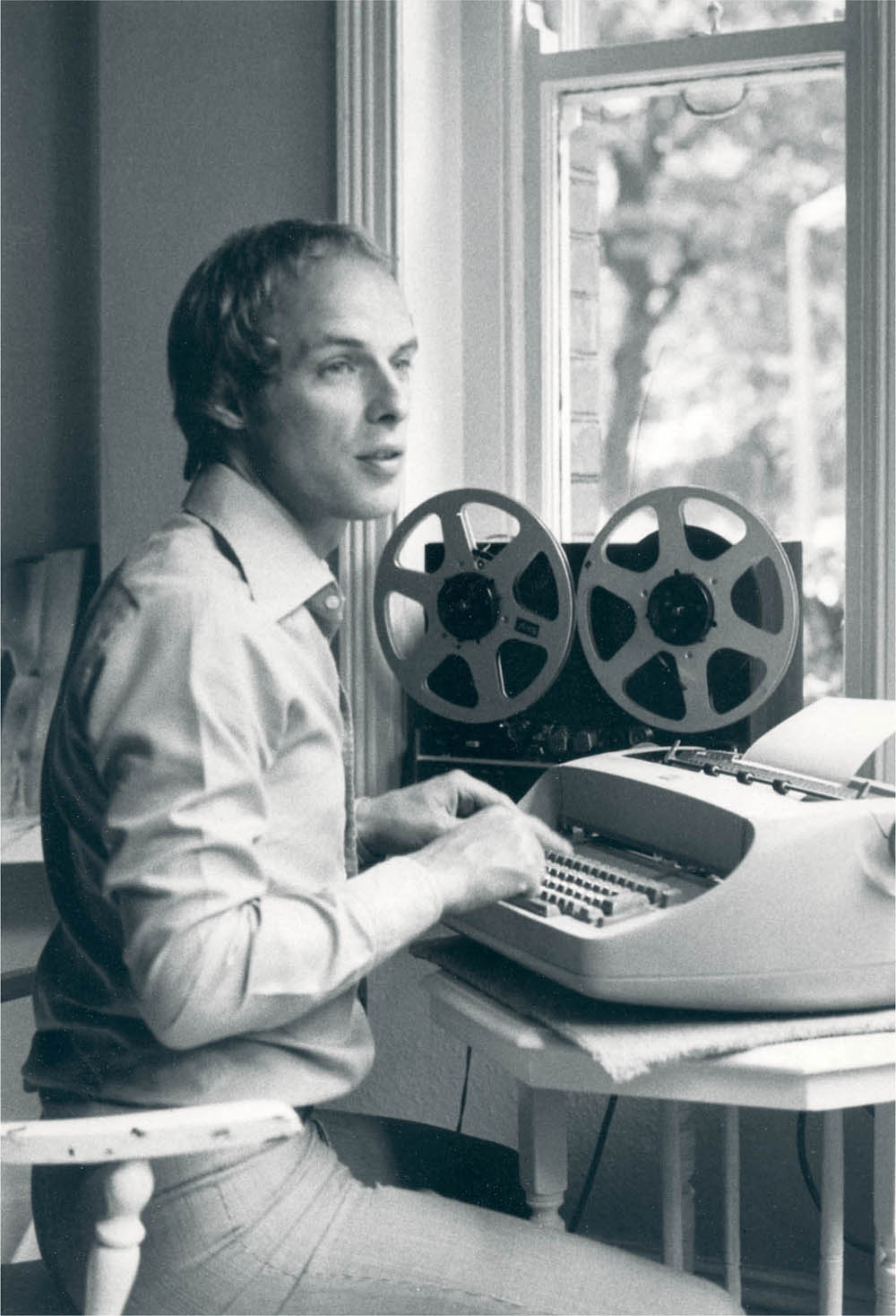

Eno in the studio, late 1970s.

Brian Eno would like to thank the many people who have helped bring these works to life, in particular Tom Bowes, Michael Brook, Gabriella Cardazzo, Rolf Engel, Roland Blum, Frank Meyer, Juan Arzubialde, Jose Smith, Marlon Weyeneth, Dominic Norman-Taylor, Paul Collister, and Nick Robertson.

Copyright 2013 by Christopher Scoates.

Foreword Extending Aesthetics Copyright 2013 by Roy Ascott

Essay Gone to Earth Copyright 2013 by Brian Dillon

Lecture Perfume, Defense, and David Bowies Wedding

Copyright 1992 by Brian Eno

Essay Learning from Eno Copyright 2013 by Steve Dietz

Interview with Brian Eno Copyright 2013 by Will Wright and Brian Eno

constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4521-2948-8

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition under ISBN: 978-1-4521-0849-0

Designed by Andrew Blauvelt and Matthew Rezac

Image retouching by Greg Beckel

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

This book is dedicated to Fiona, for her endless support and love.

Christopher Scoates

CONTENTS |

Brian Eno |

Roy Ascott |

Christopher Scoates |

Christopher Scoates |

Christopher Scoates |

Christopher Scoates |

Brian Dillon |

Brian Eno |

Steve Dietz |

Christopher Scoates |

FOREWORD

EXTENDING AESTHETICS

ROY ASCOTT

Any attempt to locate Brian Enos work within an historical framework calls for a triple triangulation, whose trig points in the English tradition would seem to be Turner/Elgar/Blake; in Europe, Matisse/Satie/Bergson, and in the United States Rothko/La Monte Young/Rorty. This triple triangulation will quickly be seen as insufficient, however, since those based on Asian and Middle Eastern cultures will also be required. Soon it would become apparent that a precise or consistent location cannot be determined, except by the abandonment of triangulation in favor of a dynamic network model. Here we would need to adopt second-order cybernetics, the recognition that attempting to measure cultural location is relative, viewer dependent, unstable, shifting, and open-ended. This conclusion reminds me that Brian was the first of my students to understand that cybernetics is philosophy, and that philosophy is cybernetics.

However, this approach to an understanding of Enos art would in itself fail to recognize his aesthetic of surrender and meditation, in which respect he seems to adopt a kind of Duchampian indifference, flowing from a process of removal of the Self from reflection, toward a quiet celebration of uneventfulness. If we take the high road to interpretation, we can say that his work exemplifies Platos theory of forms: an approach to art that invests its creativity in the Ideal (in this case binary code), and affords the expression of the Particular in sound and image, a sort of res extensa that is both both/and and either/or. To stay with philosophy, we can recognize value in Bergsons insight, We seize, in the act of perception, something which outruns perception itself. It is the specificity of that something that is recognized by those who are participants in Enos art.

Here a distinction has to be drawn between the old order of music and art in which there are listeners and viewers, and the situation that now demands an active perception, what might be called proception , in the participatory process. We can recall McLuhans dialectic of hot and cold media, where hot is too fast, too light, too loud as Brian once described the Los Angeles media scene in a KQED interview. Cold is where its at, if the viewer is to be engaged, calling for simplicity, ambiguity, open-endedness, and, specifically in Enos work, a kind of variable repetition. Mind and matter, ontology and ecology, are in a state of indefinable extension, both analytically and numerically indeterminate. His dexterity in putting time in space and space in time is beyond numerical analysis, despite such rubrics as 68 Weeks Ambience , 77 Million Paintings, 48,000 Lumens , and 400 Bodies.

Finally, we cannot grasp the ambient identity of Enos artwork without also recognizing the ambient identity of the artist himself. This demands knowing not only where to place him in the spectrum of roles across philosophy, visual arts, performance, music, social and cultural commentary, and activism, but in terms of personae, or as we say now, avatars . In the Groundcourse days, that is during the 1960s, when I first established a rather radical approach to art education in Britain (and which was emphatically the very antithesis, of course, of Groundhog days), identity, role-playing, and the variable persona were very much on the agenda, the goal of which was the construction of the Self. Throughout his career, not only has Eno explored identity, he has provided the context, employing light, sound, space, and color, in which each participant can playfully and passionately share in the breaching of the boundaries of the Self.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHRISTOPHER SCOATES

Brian Enos career as an accomplished recording artist, musical pioneer, and producer is widely documented. His innovative studio and production techniques have been critiqued and discussed at great length in articles, interviews, and essays. He has written and published on a variety of subjects including ambient and generative music, music copyright, the studio as a compositional tool, and the role of the artist and of art. His interests range widely and his pursuits are not limited exclusively to music. He has written in opposition to the wars in Bosnia and Iraq and in 1996 he provided a window into his world with the publication of a year of diary entries as A Year with Swollen Appendices . He has given illustrated lectures on art, culture, evolution, science, serenity, and complexity theory. He serves on the board of the Long Now Foundation, which in a contemporary society accustomed to acceleration, instead promotes long-term thinking as a necessary cultural construct. Indeed, his polymorphous practice is marked by an inquisitiveness that is as incisive as it is wide-ranging.

Since the mid-1960s, Eno has pursued a career in the visual arts that has developed in tandem with his work as a musician. Not as distant in their conceptual approach as one might think, these parallel practices have often informed each other, but curiously, Enos work as a visual artist has gone largely unnoticed. It is hardly surprising that he is better known for his musical output, given that it is far more easily distributed, marketed, and consumed; as Eno recognizes, If you release an album, the chance is it will be available to the whole world and everybody within a couple of days. But if you show your work in an art exhibition, the audience would have to physically be there in order to see it.

Next page